how to stop more Australian species going extinct

- Written by John Woinarski, Professor (conservation biology), Charles Darwin University

This is part of a major series called Advancing Australia, in which leading academics examine the key issues facing Australia in the lead-up to the 2019 federal election and beyond. Read the other pieces in the series here.

We need nature. It gives us inspiration, health, resources, life. But we are losing it. Extinction is the most acute and irreversible manifestation of this loss.

Australian species have suffered at a disproportionate rate. Far more mammal species have become extinct in Australia than in any other country over the past 200 years.

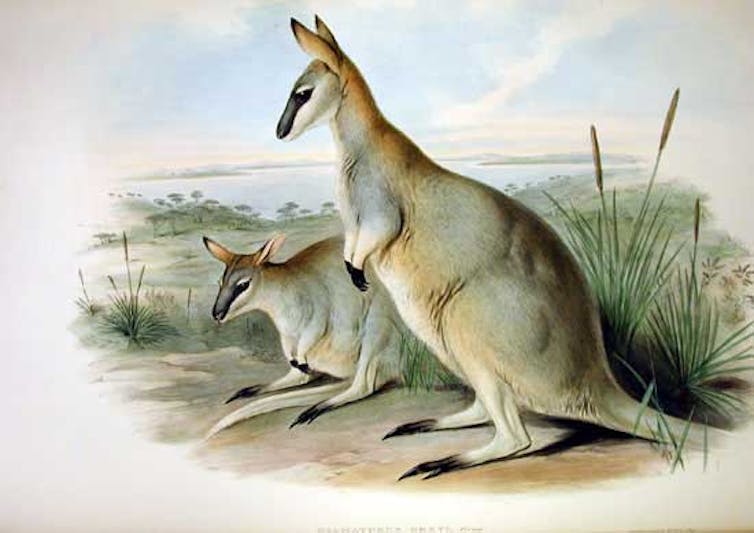

The thylacine is the most recognised and mourned of our lost species, but the lesser bilby has gone, so too the pig-footed bandicoot, the Toolache wallaby, the white-footed rabbit-rat, along with many other mammals that lived only in Australia. The paradise parrot has joined them, the robust white-eye, the King Island emu, the Christmas Island forest skink, the southern gastric-brooding frog, the Phillip Island glory pea, and at least another 100 species that were part of the fabric of this land, part of what made Australia distinctive.

And that’s just the tally for known extinctions. Many more have been lost without ever being named. Still others hover in the graveyard – we’re not sure whether they linger or are gone.

Read more: What makes some species more likely to go extinct?

The losses continue: three Australian vertebrate species became extinct in the past decade. Most of the factors that caused the losses remain unchecked, and new threats are appearing, intensifying, expanding. Many species persist only in slivers of their former range and in a fraction of their previous abundance, and the long-established momentum of their decline will soon take them over the brink.

The toolache wallaby is just one of Australia’s many extinct species.

John Gould, F.R.S., Mammals of Australia, Vol. II Plate 19, London, 1863

The toolache wallaby is just one of Australia’s many extinct species.

John Gould, F.R.S., Mammals of Australia, Vol. II Plate 19, London, 1863

These losses need not have happened. Almost all were predictable and preventable. They represent failures in our duty of care, legislation, policy and management. They give witness to, and warn us about, the malaise of our land and waters.

How do we staunch the wound and maintain Australia’s wildlife? It’s a problem with many facets and no single solution. Here we provide ten recommendations, based on an underlying recognition that more extinctions will be inevitable unless we treat nature as part of the essence of this country, rather than as a dispensable tangent, an economic externality.

We should commit to preventing any more extinctions. As a society, we need to treat our nature with more respect – our plants and animals have lived in this place for hundreds of thousands, often millions, of years. They are integral to this country. We should not deny them their existence.

We should craft an intergenerational social contract. We have been gifted an extraordinary nature. We have an obligation to pass to following generations a world as full of wonder, beauty and diversity as our generation has inherited.

We should highlight our respect for, and obligation to, nature in our constitution, just as that fusty document could be refreshed and some of its deficiencies redressed through the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Those drafting the blueprint for the way our country is governed gave little or no heed to its nature. A constitution is more than a simple administrative rule book. Countries such as Ecuador, Palau and Bhutan have constitutions that commit to caring for their natural legacy and recognise that society and nature are interdependent.

We should build a generation-scale funding commitment and long-term vision to escape the fickle, futile, three-year cycle of contested government funding. Environmental challenges in Australia are deeply ingrained and longstanding, and the conservation response and its resourcing need to be implemented on a scale of decades.

As Paul Keating stated in his landmark Redfern speech, we should all see Australia through Aboriginal eyes – more deeply feel the way the country’s heart beats; become part of the land; fit into the landscape. This can happen through teaching curricula, through reverting to Indigenous names for landmarks, through reinvigorating Indigenous land management, and through pervasive cultural respect.

We need to live within our environmental limits – constraining the use of water, soil and other natural resources to levels that are sustainable, restraining population growth and setting a positive example to the world in our efforts to minimise climate change.

We need to celebrate and learn from our successes. There are now many examples of how good management and investments can help threatened species recover. We are capable of reversing our mismanagement.

Funding to prevent extinctions is woefully inadequate, of course, and needs to be increased. The budgeting is opaque, but the Australian government spends about A$200 million a year on the conservation of threatened species, about 10% of what the US government outlays for its own threatened species. Understandably, our American counterparts are more successful. For context, Australians spend about A$4 billion a year caring for pet cats.

Environmental law needs strengthening. Too much is discretionary and enforcement is patchy. We suggest tightening the accountability for environmental failures, including extinction. Should species die out, formal inquests should be mandatory to learn the necessary lessons and make systemic improvements.

We need to enhance our environmental research, management and monitoring capability. Many threatened species remain poorly known and most are not adequately monitored. This makes it is hard to measure progress in response to management, or the speed of their collapse towards extinction.

Read more: Eulogy for a seastar, Australia's first recorded marine extinction

Extinction is not inevitable. It is a failure, potentially even a crime – a theft from the future that is entirely preventable. We can and should prevent extinctions, and safeguard and celebrate the diversity of Australian life.

Authors: John Woinarski, Professor (conservation biology), Charles Darwin University