Word games and virtue signalling as the stock exchange reworks its corporate governance code

- Written by Warren Staples, Senior Lecturer in Management, RMIT University

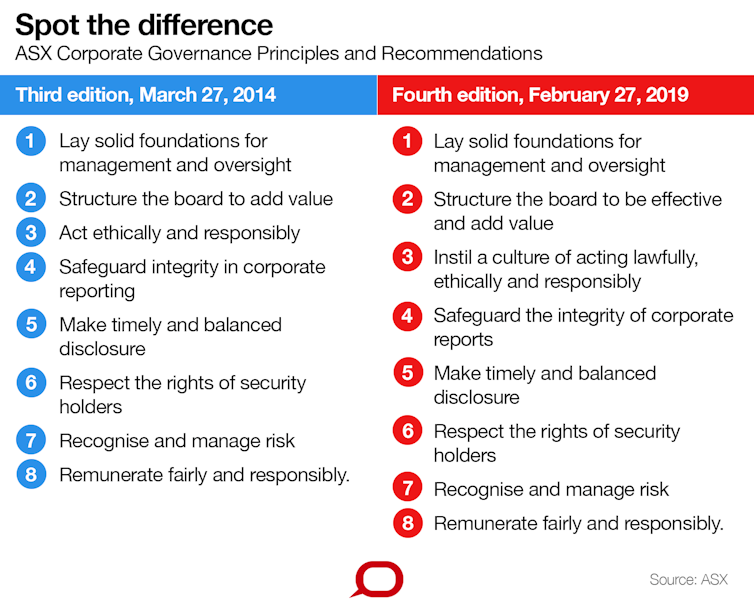

The words are a little different, but the requirements are as good as unchanged. The new Australian Securities Exchange corporate governance principles adopted last week have shuffled more words than they have altered.

When the ASX first published its governance principles in 2003 it was a decade late to the global governance party and playing catch up after the A$5.3 billion collapse of HIH Insurance.

In 2003 it modelled its new code on the British 1992 Cadbury Report.

A decade and a half on it is still playing catch-up, tweaking and reheating its code a fourth time in the wake of the banking royal commission.

The 2019 reheat is straight out of the 1992 playbook.

In 1992 City of London grandee Sir Adrian Cadbury was given the job of pulling British corporate high fliers into line after a string of scandals and collapses.

While his “restoring trust” strategy worked, it was never a rigorous, evidence-driven exercise. It was instead a cobbling together of “best practice” ideas with the aim of warding off tougher legislation.

Some 25 years on, that self regulatory approach remains deeply flawed.

Australia’s 2003 code didn’t stop the company collapses during the global financial crisis or the systemic misconduct revealed in the royal commission.

The latest revisions have variously been reported as a “potent mix of new and increased recommendations for company directors” and worthy of applause, but the commentary glosses over some fairly obvious problems with self-regulation.

The changes are minor.

What do the changes do?

The tweaks focus on the composition of the board, the role of the board in instilling a culture of acting lawfully and ethically and responsibly, and integrity of corporate reports.

Royal Commissioner Kenneth Hayne wanted boards to take responsibility for their role in establishing culture.

The ASX is signalling that it has listened to him, saying “a listed entity should articulate and disclose its values”, but it is also signalling that it doesn’t want to go as far as incorporating corporate social responsibility via a “social license to operate”, a phrase AMP chair David Murray labelled politically correct nonsense.

Other changes re-emphasise having the right people on boards (dovetailing into debates about diversity and gender equality) and safeguarding the integrity of corporate reports in light of scandals such as the collapse of Carillion in the UK, and the Gupta corruption scandal in South Africa which engulfed international heavyweights KPMG, McKinsey and Bell Pottinger.

Why are companies writing their own rules?

While the royal commission revealed damning misconduct, its final report left commentators such as Satyajit Das, Stephen Long, Alan Kohler, Adele Ferguson, and Tim Colebatch scratching their heads.

Of most concern was the heavy onus placed on the banks themselves to resolve their problems - to self-regulate.

It creates the opportunity for the Australian Securities Exchange working with the Australian Institute of Company Directors and the Business Council of Australia to claim the field for themselves.

The Institute wants to broaden directors duties but not to change board structures. The Council labels criticism “business bashing”.

Hayne wants the codes to be enforceable. But the principles are written using loose “if not, why not” language. They are anything but enforceable.

What’s the way forward?

The current ASX code should be abandoned.If Australia is to have a corporate governance code it should be written by a government-convened commission of experts and community representatives – as has happened in Germany - rather than by and for industry insiders.

Read more:

Solving deep problems with corporate governance requires more than rearranging deck chairs

What do the changes do?

The tweaks focus on the composition of the board, the role of the board in instilling a culture of acting lawfully and ethically and responsibly, and integrity of corporate reports.

Royal Commissioner Kenneth Hayne wanted boards to take responsibility for their role in establishing culture.

The ASX is signalling that it has listened to him, saying “a listed entity should articulate and disclose its values”, but it is also signalling that it doesn’t want to go as far as incorporating corporate social responsibility via a “social license to operate”, a phrase AMP chair David Murray labelled politically correct nonsense.

Other changes re-emphasise having the right people on boards (dovetailing into debates about diversity and gender equality) and safeguarding the integrity of corporate reports in light of scandals such as the collapse of Carillion in the UK, and the Gupta corruption scandal in South Africa which engulfed international heavyweights KPMG, McKinsey and Bell Pottinger.

Why are companies writing their own rules?

While the royal commission revealed damning misconduct, its final report left commentators such as Satyajit Das, Stephen Long, Alan Kohler, Adele Ferguson, and Tim Colebatch scratching their heads.

Of most concern was the heavy onus placed on the banks themselves to resolve their problems - to self-regulate.

It creates the opportunity for the Australian Securities Exchange working with the Australian Institute of Company Directors and the Business Council of Australia to claim the field for themselves.

The Institute wants to broaden directors duties but not to change board structures. The Council labels criticism “business bashing”.

Hayne wants the codes to be enforceable. But the principles are written using loose “if not, why not” language. They are anything but enforceable.

What’s the way forward?

The current ASX code should be abandoned.If Australia is to have a corporate governance code it should be written by a government-convened commission of experts and community representatives – as has happened in Germany - rather than by and for industry insiders.

Read more:

Solving deep problems with corporate governance requires more than rearranging deck chairs

Authors: Warren Staples, Senior Lecturer in Management, RMIT University