Decoding the music masterpieces: how Carmina Burana, based on Benedictine poems, travelled from Bavaria to a beer ad

- Written by Peter Tregear, Principal Fellow, The University of Melbourne

Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana is one of only a handful of 20th century classical concert pieces that can claim to have become embedded in popular culture. Its opening movement in particular has featured in epic film battle scenes, coffee, beer and cologne commercials, dancefloor hits and even inspired an internet meme about misheard lyrics.

Both the origins of the work and its composer are, however, much less known. Born in Munich in 1895, Orff’s lasting musical contribution outside composition was in the field of music education.

What we know today as Orff Schulwerk is an approach to teaching music that encourages children to explore and develop their musical creativity through singing, improvisation, movement, and rhythmic play.

Orff Schulwerk became influential across the West in the years after the second world war (and helped make percussion instruments in particular part of the standard kit of the school music room) but Carmina Burana — the sound of which reflects some of the vocal and percussive interests of the Schulwerk approach — dates from just before the onset of that war.

Premiering in June 1937 at the Frankfurt Opera, its compositional history therefore also intersects with aspects of the racial, cultural and aesthetic cultural policies the Nazi Party introduced across Germany after its rise to power in 1933.

An earthy manuscript

The title simply means “Songs from Beuern” in Latin. Beuern is a variant of the German word for Bavaria, Bayern, but here it specifically refers to a village south of Munich at the foothills of the Bavarian Alps.

The village was home to a Benedictine monastery founded in 733. When it was dissolved in 1083, its library was transferred to the Court Library at Munich.

There, in 1847, a modern edition was made of perhaps the most remarkable work in the collection: a beautifully illuminated manuscript of secular poems in both Latin and Middle High German. These “Carmina Burana” soon became well-known across Europe.

In the mid 1930s Orff asked the German poet and jurist Michel Hofmann to organise 24 of those poems into a libretto for what he envisioned as a kind of secular oratorio with staging elements. The original poems had been preserved with their own melodies, but Orff was not aware of their existence when composing his own settings.

The full title — Songs of Beuern: Secular songs for singers and choruses to be sung together with instruments and magical images — reminds us the original performances were more than concerts. They were envisioned as theatrical events.

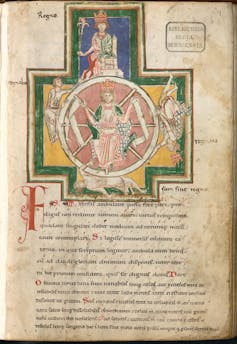

Codex Buranus (Carmina Burana) with the Wheel of Fortune, Bavarian State Library, Munich. Circa 1230.

Wikimedia Commons

Codex Buranus (Carmina Burana) with the Wheel of Fortune, Bavarian State Library, Munich. Circa 1230.

Wikimedia Commons

The famous opening chorus, O Fortuna, velut Luna (O Fortune, like the moon) refers to the Wheel of Fortune and the vagaries of fate. Returning in full at the end, the chorus gives the work a dramatic and musical frame.

Inside that frame, Orff and his librettist placed three groups of poems that deal with, respectively, the transient joys of springtime (Primo Vera), the tavern (In Taberna), and erotic love (Cour d’amours).

Much of the pleasure I suspect we receive from Carmina Burana comes not just from the high literary quality of these poems but also from the fact they concern themselves with topics far from what we might imagine were the usual interests of a benedictine monastery. They can be punchy, earthy, funny — and sometimes surprisingly confronting.

A Roasting Swan laments its fate to those who are about to consume it.I would challenge any carnivore to hear the extraordinary twelfth movement Olim Lacus Colueram (“Once I lived on lakes”) which gives voice to a roasting swan, and not be drawn to contemplate - if only for a moment - vegetarianism.

But is it fascist?

In his book The Twisted Muse (1997), musicologist Michael Kater asserts that Orff was a central figure in what he describes as a “School of Nazi modernism” which also included composers Werner Egk, Boris Blacher, Gottfried von Einem and Rudolf Wagner-Régeny.

A popular and critical success from its first performance, Carmina Burana was performed regularly in Germany throughout the second world war. The subject matter certainly appealed to Nazi sensibilities that sought to legitimise the Third Reich through association with past empires, particularly the Germany of the medieval era.

But what about the music?

Being approved by a fascist regime does not in and of itself make something fascist. And, in any case, it is notoriously difficult to try and define what a fascist music might be as we are more wont to do in the case of, say, architecture.

As I have suggested elsewhere, we could be forgiven in fact for concluding that Nazism (and fascism more generally) is something which happens to music and musicians, and not something with which a musical work can be complicit in a uniquely musical way.

Read more: How the Nazis used music to celebrate and facilitate murder

Yet I do think it is possible to explore such a possibility — albeit with due caution. Hannah Arendt, who spent a great deal of her later life trying understand how Germany had descended into fascism, described in her book The Origins of Totalitarianism one tell-tale characteristic of fascism as being the “emancipation of thought from experience”: a kind of willed stupidity.

Can a piece of music encourage or mimic such thinking? Can it foster a kind of of “stupid” listening? Well, as far as Carmina Burana is concerned, we might note its heavy reliance on the repetition of small musical motives does lend the work a sense of unquestioned (or, at worst, unquestionable) ritualistic force which might lead us to think something similar.

André Rieu conducts the opening chorus O Fortuna.A visual parallel might be Albert Speer’s infamous Cathedrals of Light, the array of spotlights he used to monumentalise the Nazi Party rallies in Nuremberg around the same time as Orff was composing Carmina Burana. Here we are certainly presented with an effect without just cause - the awe-inspiring vista (also achieved in no small part by the sheer blunt force of repetition) overwhelms us without encouraging us to reflect on whether that response is actually merited by what the spotlights accompany.

The deployment of artistic effects without legitimate justification is, however, not just a property of fascist aesthetics. It is also a commonly asserted property of kitsch. Should we be surprised, then, to find that the opening chorus of Carmina Burana also now pops up in concerts by the so-called King of Classical kitsch, André Rieu?

Read more: André Rieu gives his audience exactly what they want: entertainment

The frequent use of this opening chorus as an advertising jingle is also, I think, revealing. A famous Carlton and United advertisement for draught beer declared to its audience that they were watching, simply, “a big ad.”

Here, the ad-makers themselves seem to have recognised, named, and exploited the empty grandiosity some would say indeed lies at the heart of the music.

A Big Ad, indeed.That opening chorus has also made an appearance in the soundtracks of numerous feature films, most notably 1981’s Excalibur, where the shared medieval fantasy elements no doubt made some dramatic sense. But it has also been frequently applied to subject matter far removed from medieval topics; and often for comic and ironic effect.

In a 2001 essay for the New York Times the renowned musicologist Richard Taruskin went as far as to suggest that Orff’s music “can channel any diabolical message that text or context may suggest, and no music does it better”.

He continued “it is just because we like it that we ought to resist it”.

‘Behold Excalibur!’ Carmina Burana adds oomph to an already powerful narrative.Nevertheless, as another commentator subsequently noted, Taruskin’s description of the work’s effect is also “almost the definition of a guilty pleasure.”

Maybe that’s the best place for us to start our engagement with the work today. Let’s continue to enjoy and be impressed by Carmina Burana — but also let’s not forget to ask ourselves why we might find it so enjoyable and impressive in the first place.

The Sydney Philharmonia Choir performs Carmina Burana this weekend and Melbourne Symphony Orchestra will perform it in July.

Authors: Peter Tregear, Principal Fellow, The University of Melbourne