Book review: Geoffrey Robertson makes the case for naming and shaming human rights abusers

- Written by George Newhouse, Adjunct Professor of Law, Macquarie University

Geoffrey Robertson is one of Australia’s most acclaimed international jurists and human rights advocates. His latest book, Bad People – and How to Be Rid of Them, explains the history of international human rights law and acknowledges its failings.

Bad People is not a textbook; it is aimed at anyone with an interest in the international human rights framework and its enforcement mechanisms.

Most importantly, it is a call to action for Australians and others in democracies to demand the introduction of “Magnitsky laws”.

Magnitsky laws are named after a Russian whistleblower, Sergei Magnitsky, who was tortured and died after exposing a massive tax fraud scheme involving Russian officials. These laws seek to combat human rights abuses by naming, blaming and shaming individuals, denying them the right to enter democratic nations, stripping them of ill-gotten funds, and barring them and their families from local schools and hospitals.

Magnitsky was a Moscow lawyer and tax auditor who died in custody in Russia at the age of 37.

Alexander Zemlianichenko/AP

Magnitsky was a Moscow lawyer and tax auditor who died in custody in Russia at the age of 37.

Alexander Zemlianichenko/AP

The US was the first country to pass such laws in 2012 to sanction Russian officials and Chechen warlords, sending a strong signal to the Kremlin that action could and would be taken for human rights breaches.

Since then, the US has used the Global Magnitsky Act to impose sanctions on more than 200 individuals and entities from two dozen countries, including Saudi Arabia, China, South Sudan, Myanmar, Iraq and Cambodia.

Robertson’s response to the failure of the international human rights framework is to promote powerful Magnitsky laws as a “plan B” to coordinated international action.

Bad People – and How to Be Rid of Them, by Geoffrey Robertson.

Penguin Books Australia

Bad People – and How to Be Rid of Them, by Geoffrey Robertson.

Penguin Books Australia

How international courts have been weakened

Robertson charts the rise of human rights immediately after the horrors of the second world war, and then despairs of the growing trend of nations retreating from the jurisdiction of international courts or refusing to comply with their rulings.

Robertson describes how the United Nations succeeded in establishing a coherent human rights regime, but failed to carve out effective accountability mechanisms to enforce breaches. Instead, enforcement relies on individual nations’ leaders being motivated to legislate human rights into their domestic laws.

Although the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights has been broadly accepted, punishment for war crimes and crimes against humanity has been inconsistent and complex.

Consequently, Robertson argues the International Criminal Court (ICC) does not serve as a deterrent to perpetrators of most human rights abuses.

Eroded confidence in international law

The book provides a useful history of the ICC and the way the US, China and Russia have limited its operations by using their veto powers when legal action is proposed against them or their allies.

In the past four years, for instance, Russia has vetoed ICC action 14 times, China five times and the US twice. Robertson suggests the mere threat of a veto by superpowers behind the scenes have seen other initiatives withdrawn.

As a result, Robertson laments the once-powerful ICC is now confined to punishing rebel warlords and leaders of pariah countries.

More than 70 years after the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the growing threats of isolationist foreign policies and anti-democratic regimes are pulling at the threads of our international human rights framework. Shifting geopolitical balances and the populist politics of Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Narendra Modi, Donald Trump and the Brexit campaign have eroded confidence in a global system of law and order.

Read more: Australia must do more to ensure Myanmar is preventing genocide against the Rohingya

Australia is not immune from this trend. In February 2020, the ICC prosecutor described Australia’s offshore detention regime as “cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment”.

But, the ICC decided not to prosecute the Australian government, despite saying its actions appeared “to constitute the underlying act of imprisonment or other severe deprivations of physical liberty” forbidden under international law.

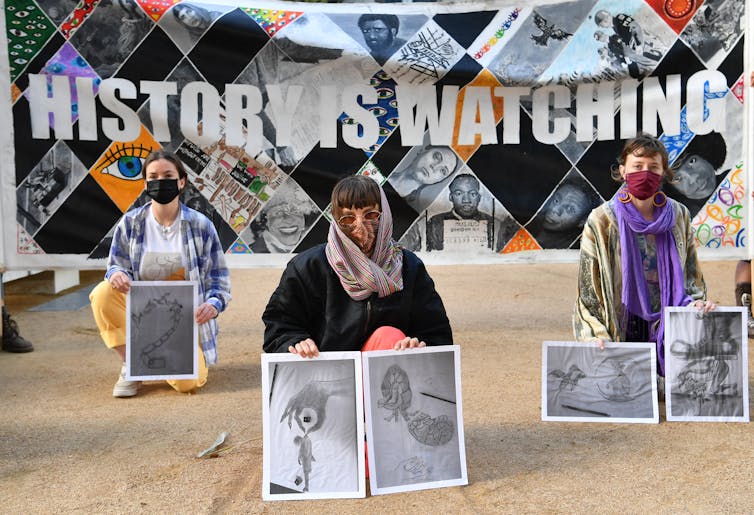

A protest against the continued detention of asylum seekers in Australia.

Darren England/AAP

A protest against the continued detention of asylum seekers in Australia.

Darren England/AAP

The problem with Magnitsky laws

Robertson’s solution is to impose sanctions against individuals, corporations and other entities.

He argues Magnitsky laws are not an alternative to coordinated international criminal justice, but an assertion of the fundamental values that countries insist should be respected by other nations.

The problem is these types of sanctions can be abused for political reasons. We have already seen the tit-for-tat actions of nations that bring sanctions against the citizens of their enemies, such as the Russian counter-sanctions against US citizens in 2013, including former Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff.

Read more: Canada's growing challenges with economic sanctions

Among democratic nations, it is unlikely Magnitsky laws would ever be used against friendly allies. Can you imagine any of Australia’s allies sanctioning an Australian official for a First Nations’ death in custody or for the over-representation of First Nations people in the country’s criminal justice system?

If enforcement of human rights breaches is seen as political or inconsistent, then Magnitsky laws may not be the universal panacea Robertson suggests. However, this doesn’t mean the push for individual accountability is not justified. As he writes,

human rights are not rights in any meaningful sense unless they are capable of enforcement.

Robertson leaves us with a sensible pathway to a better world through laws that hold individuals accountable for their evil deeds. Magnitsky sanctions might, at least, make murderers, crooks and abusers think twice before implementing their plans.

Geoffrey Robertson will be speaking across Australia in the coming weeks, with engagements in Melbourne on May 22 and Sydney on May 25 and 26, to be followed by Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth.

Authors: George Newhouse, Adjunct Professor of Law, Macquarie University