All the hype around Libra is a red herring. Facebook's main game is Calibra

- Written by Priya Dev, Blockchain Researcher & Lecturer Data Analysis, Australian National University

Amid the hype around Facebook’s plan to launch its own cryptocurrency, Libra, there’s one big question. How is the company going to profit from it?

The project relies on developing blockchain technology. But blockchain’s whole raison d'être is to challenge the way corporate capitalism and businesses like Facebook make money.

Facebook has also established, with several dozen equally capitalistic partners, the Libra Association, a nonprofit organisation based in Switzerland, to spearhead the venture.

Read more: The lowdown on Libra: what consumers need to know about Facebook’s new cryptocurrency

After years of copping criticism for questionable business practices, has Facebook decided to take an altruistic turn?

Probably not. It’s more likely that blockchain, and even Libra, is a means to a end; it’s about Facebook wanting to be not only the world’s biggest social media platform but also the globe’s go-to marketplace, putting Amazon, eBay, Apple and Google in the shade.

To appreciate why this suggestion isn’t also hyperbole, we need to talk not so much about Libra but its companion technology, the “custodial wallet” called Calibra.

Blockchain, but not blockchain

First, let’s do a quick recap of some fundamentals.

In 2008, a person or group calling themselves Satoshi Nakamoto proposed a method for transacting over the internet without a trusted third party such as a bank. It uses a distributed ledger known as a blockchain and cryptography to maintain a tamper-proof record of ownership of electronic cash – hence the term cryptocurrency.

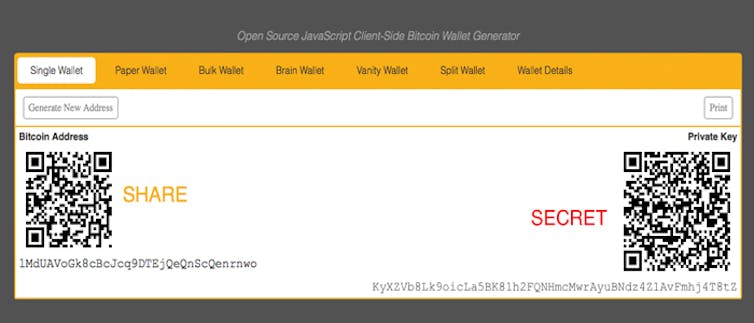

Blockchain’s core innovation is to do away with the need for trusted entities like banks. So how do people safely send or receive cryptocurrency? Well, they can use a “cryptocurrency wallet”. A cryptocurrency balance is recorded against a blockchain address. Proving ownership depends on a secret code (or “private key”) known only to the owner. The “wallet” is essentially software that allows people to manage their private keys and authorise transactions.

Facebook has other ideas for its cryptocurrency. The Libra Association says it wants to “make sending money as easy and cheap as sending a text message”. Tapping addresses and secret codes into a wallet interface every time wouldn’t be that easy. These codes can be long – up to 64 characters, compared to 16 for a credit card.

Cryptocurrency Keys.

https://en.bitcoinwiki.org/index.php?curid=271198

Cryptocurrency Keys.

https://en.bitcoinwiki.org/index.php?curid=271198

So Facebook will instead provide a “custodial wallet” – Calibra. It will be the custodian of your cryptocurrency, much like a bank is custodian of your money, and thus manage your wallet for you.

Facebook can certainly argue that this makes it much easier to use Libra – and it wants to make Libra easy to use so you can buy items through Facebook and its other platforms, such as Whatsapp and Instagram.

But this aspect has little to do with the original ideals behind blockchain. It makes Calibra more like a bank, with a record of your electronic payments. It will know everything you buy or sell through its wallet; and it will share “Calibra customer data with managed vendors and service providers — including Facebook”.

How Facebook monetises data

Why is this important? Because Facebook is in the business of gathering your personal data.

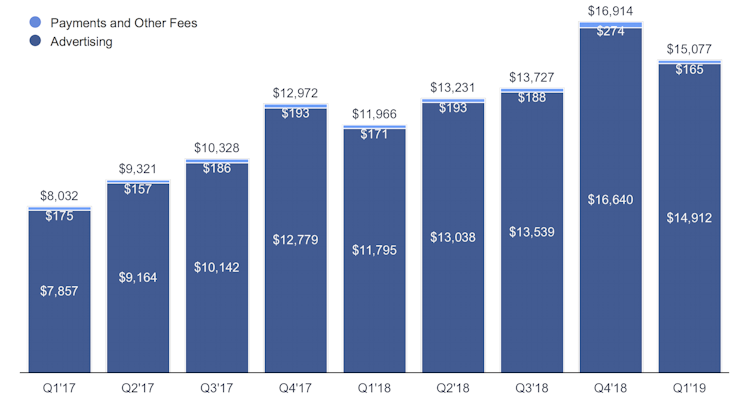

It now uses this information to make about 99% of its income from selling advertising – US$14.9 billion in the first quarter of 2019 alone.

Facebook revenue, in millions.

Facebook

Facebook revenue, in millions.

Facebook

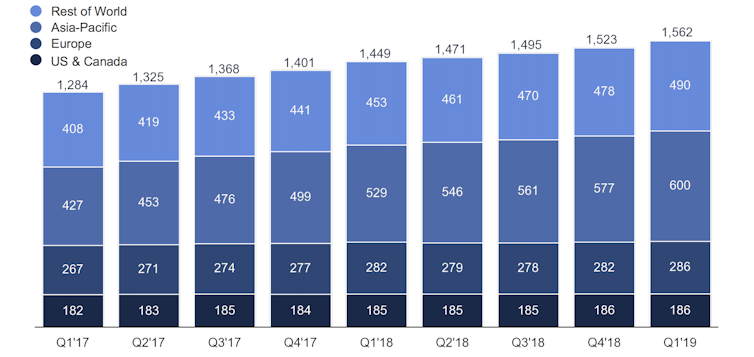

Its value as an advertising delivery mechanism comes not just from its sheer number of users (1.56 billion daily users, and 2.37 billion monthly users) but from what it knows about them.

Facebook daily active users, in millions.

Facebook

Facebook daily active users, in millions.

Facebook

This goes way beyond basic personal details like your birthdate. Almost everything about Facebook is designed to get you to reveal personal information. You do this through what you post and the posts you like or respond to. You do this even when not directly using Facebook. Lots of online stores report back to Facebook when you visit them, for example.

Read more: Explainer: what is surveillance capitalism and how does it shape our economy?

Identifying key personality traits can be used to predict purchasing behaviour – or political preference, as demonstrated in the Cambridge Analytica controversy. The British-based political consultancy bragged it effectively swung the US 2016 election to Donald Trump by using Facebook to harvest user data and then directing customised political messages to users’ newsfeeds.

Read more: We need to talk about the data we give freely of ourselves online and why it's useful

While there is some scepticism about Cambridge Analytica’s electoral impact, it is generally agreed the process of “micro-targeting” can be very effective for marketers.

So the more information Facebook has about you, the more money it can potentially make by influencing you.

Becoming bigger than Amazon

There’s more.

Facebook’s value as an advertising powerhouse has made its founder, Mark Zuckerberg, extremely wealthy – worth an estimated US$73 billion. But that’s less than half of Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, who’s worth US$158 billion.

Both companies are in the business of helping merchants sell products. But Amazon’s position as an online marketplace is more lucrative than Facebook’s role as a shop window. Amazon can take a cut from every sale. Its retail business makes up about 80% of its US$950 billion value, which is greater than Facebook’s total value of US$550 billion.

What if Facebook could be both the shop window and the cash register? What if it no longer just introduced users to merchants but also became the digital marketplace supporting those merchants? What if it could collect not just social data but also buyer history data?

This is what Libra, and more critically, Calibra, could mean for Facebook.

Libra’s an important part of this picture. But it’s Calibra that could deliver the data Facebook needs to become possibly the most valuable, and powerful, online company in the world.

Authors: Priya Dev, Blockchain Researcher & Lecturer Data Analysis, Australian National University