the Terracotta Warriors & Cai Guo-Qiang

- Written by Alison Carroll, Senior Research Fellow, Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne

The oft-quoted saying “may you live in interesting times” has been (rightly or wrongly) interpreted as a Chinese curse. The exhibition Terracotta Warriors & Cai Guo-Qiang at the National Gallery of Victoria has a similar subtle duality: the implication of threat in what might seem benignly interesting.

This is reflected in the warriors themselves, 2200-year-old figures of supreme beauty made to accompany their Emperor into death, and mirrored by very contemporary works (some made in the last few weeks) of inspiring ethereality, formed using that most mercurial and potentially deadly Chinese invention – gunpowder.

Installation view of Standing archer on display as part of Terracotta Warriors: Guardians of Immortality and Cai Guo-Qiang: The Transient Landscape at NGV International.

© Sean Fennessy

Installation view of Standing archer on display as part of Terracotta Warriors: Guardians of Immortality and Cai Guo-Qiang: The Transient Landscape at NGV International.

© Sean Fennessy

The eight individual (and individualised) serene and commanding warriors who march down the main hall of the gallery’s temporary exhibition space come from the burial site of Chinese Emperor Qin Shihuang who died in 210 BCE. These figures are answered by contemporary artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s murmuration or sweep of birds (again individually made, similarly in clay,) flying miraculously in unison.

That each individual warrior (some 8000 apparently exist, most still buried) and each bird is given this respect and value within the group reflects an understanding espoused by Confucius some hundreds of years before the warriors were made.

Installation view of Kneeling archer on display as part of Terracotta Warriors: Guardians of Immortality and Cai Guo-Qiang: The Transient Landscape at NGV International.

© Sean Fennessy

Installation view of Kneeling archer on display as part of Terracotta Warriors: Guardians of Immortality and Cai Guo-Qiang: The Transient Landscape at NGV International.

© Sean Fennessy

It’s an element that challenges the Western notion of the supremacy of the individual above and beyond the group. It explains the potential power of Chinese culture – the capacity to move a huge civilisation in a direction that benefits every person.

This exhibition reveals this reality, albeit subtly. The Emperor was just one person, albeit at the apex, within this system and was expected to behave with moral honour and rectitude – or bring down the wrath of heaven on the whole empire.

Each warrior and starling retain this sense of themselves as a part of a wider whole. For a Westerner to see this, and reflect, is to better understand our own culture.

Installation view of Kneeling archer (detail) on display as part of Terracotta Warriors: Guardians of Immortality and Cai Guo-Qiang: The Transient Landscape at NGV International.

© Sean Fennessy 20190523_NGV_

Installation view of Kneeling archer (detail) on display as part of Terracotta Warriors: Guardians of Immortality and Cai Guo-Qiang: The Transient Landscape at NGV International.

© Sean Fennessy 20190523_NGV_

As leaders of society in Confucian China, scholars espoused the ideal of controlling one’s vital energy towards the good for all; in art, scholar-artists directed this inner energy, called qi (or chi), into a single perfect brushstroke. The warriors have this “less-is-more” inner strength, taut in their bodies yet appearing calm, faces determined yet full of life, hands ready for action but so soft you can almost feel the flesh.

Cai harnesses this inner force through gunpowder: the explosive energy resulting in the final flourish, like the brushstroke of old finally laid down with such controlled bravura.

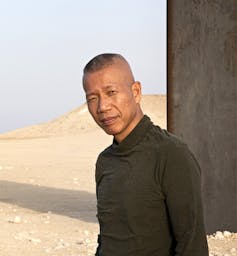

Cai Guo-Qiang, Qatar, 2016.

Photo by Wen-You Cai, courtesy Cai Studio

Cai Guo-Qiang, Qatar, 2016.

Photo by Wen-You Cai, courtesy Cai Studio

It takes time to see the restraint and admire its qualities. Western art has traditionally admired the opposite, of “more-being-more”, especially art made at the height of Western colonial power.

Cai talks of the essential tension in his work between harmony and chaos, words so central to Chinese concepts of “world balance”, as articulated by Confucius and still resonant today. I interviewed Cai in 2013 in Brisbane for the film series A Journey Through Asian Art. He talked then as now of the seeming calmness of the gunpowder contrasted with its ignited energy, reflecting on the invisible forces that “inform the spirit of Chinese art and culture”.

The Cai work at NGV has a subtitle of “The Transient Landscape”, and indeed, besides the murmuration of birds, he has evoked the inexorable forces of the natural world in his room mural of dying peonies, with a funereal “grave” of singed terracotta flowers in its centre.

In another room, a landscape of Mt Li, the sacred peak where the Qin Emperor was buried, is further suggested as a rise on the horizon delineated in that spare, harsh gunpowder flash.

Installation view of Terracotta Warriors: Guardians of Immortality and Cai Guo-Qiang: The Transient Landscape at NGV International, 24 May – 13 October 2019. © Cai Guo-Qiang.

Photo © Sean Fennessy

Installation view of Terracotta Warriors: Guardians of Immortality and Cai Guo-Qiang: The Transient Landscape at NGV International, 24 May – 13 October 2019. © Cai Guo-Qiang.

Photo © Sean Fennessy

The exhibition is fleshed out, if that is the right term for a show exploring burial and death, by further ancient objects from various museums in Shaanxi, the exhibition partner. These include the small, slender, even elfin female figure, also made in terracotta during the (next) Han dynasty. In her own case, in the last room, she seems to be smiling to herself, perhaps at the display of pomp and circumstance of these men around her.

The contrasts here, or binaries if you wish, are revealing and many: life and death, harmony and chaos, energy and control, art and politics. But perhaps this last couplet is not so antithetical, especially in these interesting times.

The first major exhibition of ancient Chinese art in Australia, shown in Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide in 1977, came in the wake of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s official recognition of the People’s Republic and two visits there. This was a political act of significance internationally.

The 1982-3 exhibition of Terracotta Warriors shown in all the mainland state capitals, which again had Prime Ministerial support, (from Malcolm Fraser), was timed to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Australia and China. Of course, there is nothing wrong with this – how many Euro-American grand exhibitions reinforce diplomatic relations, passing without comment?

Qin Shihuang’s terracotta warriors, Pit 1, Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE) (detail)

© Shaanxi History Museum (Shaanxi Cultural Heritage Promotion Center) and Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum

Qin Shihuang’s terracotta warriors, Pit 1, Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE) (detail)

© Shaanxi History Museum (Shaanxi Cultural Heritage Promotion Center) and Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum

At the end of 2018, the Victorian Government announced a Memorandum of Understanding with China. Chinese Premier Xi Jinping acknowledged the discussion of culture (or civilisation) as a political force a few weeks ago in Beijing saying, “… it is foolish to believe that one’s race and civilisation are superior to others and it is disastrous to wilfully reshape and even replace other civilisations”.

Xi, like Whitlam and Fraser before him, sees the links between history, politics and culture. Confucius surely would have nodded in agreement.

As ever, if the art is without perceived value no amount of political encouragement will lift its success.

Installation view of Cai Guo-Qiang’s Murmuration.

(Landscape) 2019 (detail) Realised in Dehua, Fujian

province and Melbourne, commissioned by the NGV.

Proposed acquisition supported by Ying Zhang in

association with the Asian Australian Foundation, 2019

NGV Foundation Annual Dinner and 2019 NGV Annual

Appeal, on display at NGV International © Cai Guo-

Qiang.

© Tobias Titz Photography

Installation view of Cai Guo-Qiang’s Murmuration.

(Landscape) 2019 (detail) Realised in Dehua, Fujian

province and Melbourne, commissioned by the NGV.

Proposed acquisition supported by Ying Zhang in

association with the Asian Australian Foundation, 2019

NGV Foundation Annual Dinner and 2019 NGV Annual

Appeal, on display at NGV International © Cai Guo-

Qiang.

© Tobias Titz Photography

The late Edmund Capon, long-term recent director of the Art Gallery of NSW, wrote the catalogue for the 1982-3 Warriors exhibition, a text remarkable for its expertise in ancient Chinese culture. He championed a return Warriors show in Sydney in 2010, and untiringly advocated for understanding of Chinese culture in person, on film, and through his museum work.

This exhibition is about life and death. Its aim and scope are as big as humanity can conjure. I like to think Edmund is sitting in true ancestor mode (with his arms resting on his knees), grinning at this – the first NGV Winter Masterpiece exhibition from Asia – and the fact that a new generation of people, especially in Melbourne, get to see it. These are interesting times indeed, but, one hopes, in the best way.

Terracotta Warriors & Cai Guo-Qiang is on at the National Gallery of Victoria until October 13.

Authors: Alison Carroll, Senior Research Fellow, Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne