how does preferential voting work in the House of Representatives?

- Written by Stephen Morey, Senior Lecturer, Department of Languages and Linguistics, La Trobe University

At the May 18 federal election, voters in every electorate of Australia’s House of Representatives will have a choice of multiple candidates. Preferential voting means that we rank candidates in the order that we prefer them.

So, how does preferential voting work?

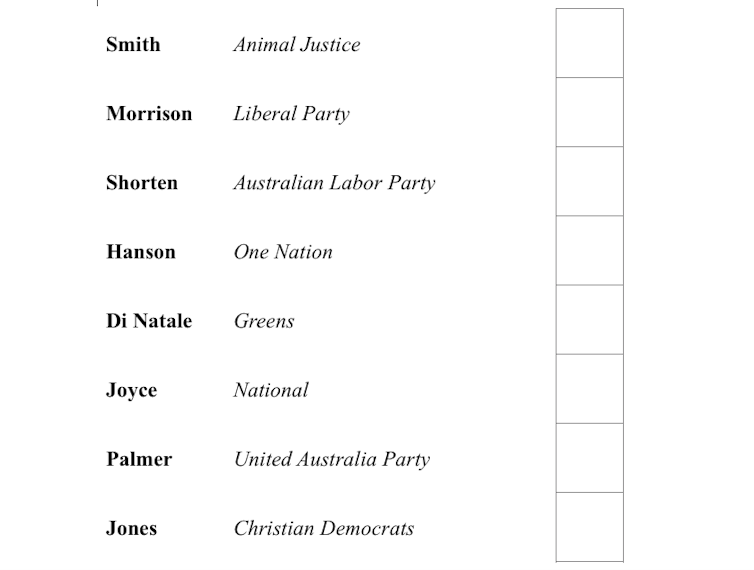

Voters must number every box on the ballot paper. You can number them in any order, but you must number each of them. So if there are eight candidates, you must number one to eight inclusive.

Read more: How much influence will independents and minor parties have this election? Please explain

You don’t have to follow how-to-vote cards

Supporters of political parties hand out “how-to-vote” cards that advise voters how to fill out their preferences, but you certainly don’t have to follow them. You can still vote “1” for that party’s candidate, but change the order of your later preferences.

For example, suppose you want to vote for the candidate of the Liberal Party, and it recommends that you vote “1” Liberal and “2” for the candidate of the United Australia Party (UAP), led by Clive Palmer. If you don’t like the UAP, you can still vote Liberal “1”, and mark your other preferences in any order you choose.

As long as each candidate receives a different preference, your vote is formal (valid). And as long as you vote “1” for the Liberal party candidate, your vote is still a full vote for the Liberals.

What a valid vote looks like

Let’s take an imaginary electorate that has the following candidates.

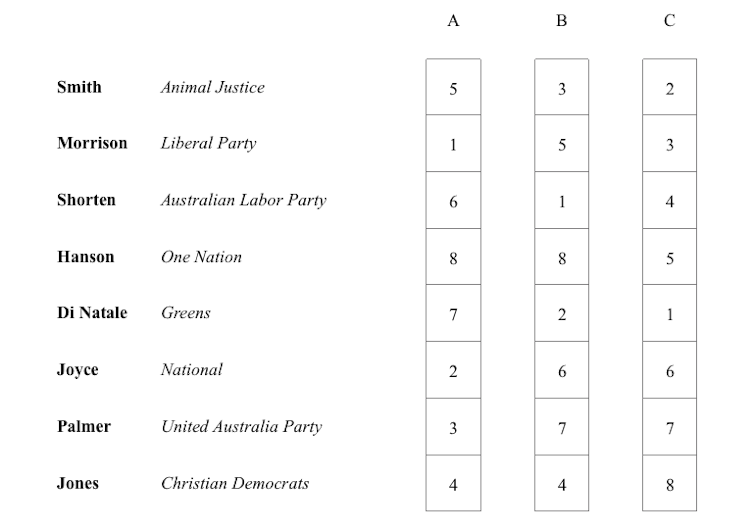

Below are a number of possible ballots:

in column A we show a ballot for the Liberal Party candidate that next preferences the National Party, then the United Australia (Clive Palmer’s party), and then the Christian Democrats. Note that all eight boxes must be marked

in Column B we show a ballot for the ALP candidate

in Column C a ballot for the Greens candidate that next preferences the Animal Justice candidate, and then the Liberal candidate.

Below are a number of possible ballots:

in column A we show a ballot for the Liberal Party candidate that next preferences the National Party, then the United Australia (Clive Palmer’s party), and then the Christian Democrats. Note that all eight boxes must be marked

in Column B we show a ballot for the ALP candidate

in Column C a ballot for the Greens candidate that next preferences the Animal Justice candidate, and then the Liberal candidate.

All those ballots are formal, because they mark all the numbers on the ballot paper in sequence.

If a ballot paper repeats a number or does not number each of the boxes, then it is informal and cannot be counted. So all voters are advised to be careful, and number each of the boxes on the ballot.

Read more:

More grey tsunami than youthquake: despite record youth enrolments, Australia’s voter base is ageing

Key mistakes to avoid

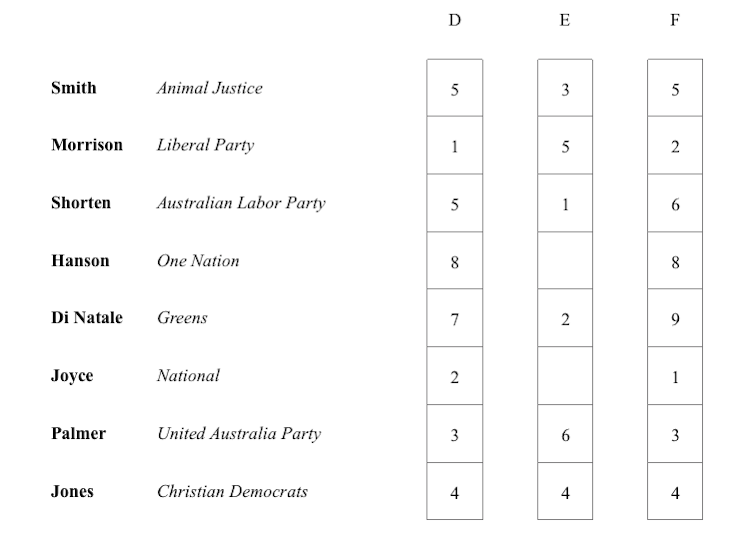

Here are some examples of informal ballot papers that cannot be counted.

in Column D, the numeral “5” is repeated, so the ballot is informal

in Column E, two boxes are unmarked, so that ballot is also informal

in Column F, there is gap in what should be a sequence of consecutive numerals, so that ballot is also informal.

All those ballots are formal, because they mark all the numbers on the ballot paper in sequence.

If a ballot paper repeats a number or does not number each of the boxes, then it is informal and cannot be counted. So all voters are advised to be careful, and number each of the boxes on the ballot.

Read more:

More grey tsunami than youthquake: despite record youth enrolments, Australia’s voter base is ageing

Key mistakes to avoid

Here are some examples of informal ballot papers that cannot be counted.

in Column D, the numeral “5” is repeated, so the ballot is informal

in Column E, two boxes are unmarked, so that ballot is also informal

in Column F, there is gap in what should be a sequence of consecutive numerals, so that ballot is also informal.

Why do we have preferential voting?

The basis for preferential voting is that the winning candidate must receive at least 50%, plus one vote, to be elected. In other words, the winning candidate is supported by at least half the voters.

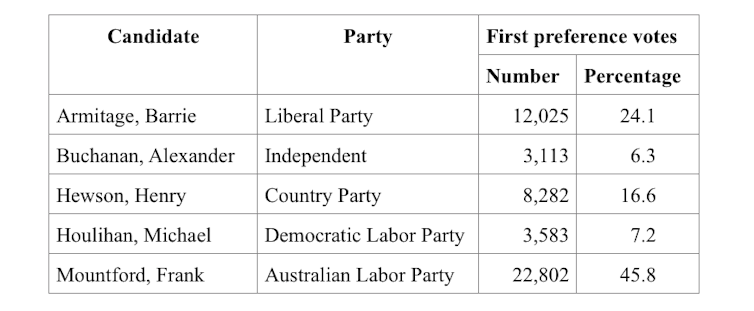

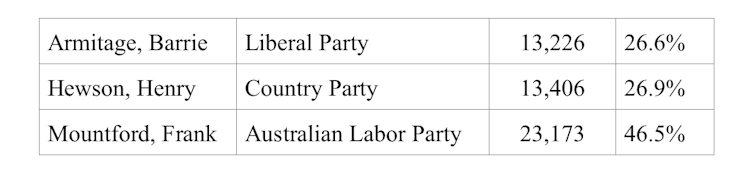

The candidate who has the highest number of votes at the first stage of the count (first preferences) does not necessarily win. It can happen that a candidate with fewer first preferences, nevertheless goes on to win. The most notable case was at the 1972 election in the federal division of McMillan, in rural Victoria:

Why do we have preferential voting?

The basis for preferential voting is that the winning candidate must receive at least 50%, plus one vote, to be elected. In other words, the winning candidate is supported by at least half the voters.

The candidate who has the highest number of votes at the first stage of the count (first preferences) does not necessarily win. It can happen that a candidate with fewer first preferences, nevertheless goes on to win. The most notable case was at the 1972 election in the federal division of McMillan, in rural Victoria:

Although the Labor candidate had received the highest number of first preference votes, he did not reach 50% and was not elected.

Because of that, the candidate with the smallest number of votes, Buchanan, was excluded from the count, and the second preference of each of his ballot papers was transferred, with the same effect as first preferences, to the candidate marked “2”.

This left four candidates in the count. If, at this point in the count, the cumulative total of one of the candidates continuing in the count had exceeded 50% of all ballots, that candidate would be declared elected.

That did not happen, so the continuing candidate with the fewest votes, Houlihan, was excluded. That led to the transfer of Houlihan’s ballots to the candidates marked as the next available preference.

Read more:

A matter of (mis)trust: why this election is posing problems for the media

When both Buchanan and Houlihan had been excluded and their ballots transferred, the third count was as follows:

Although the Labor candidate had received the highest number of first preference votes, he did not reach 50% and was not elected.

Because of that, the candidate with the smallest number of votes, Buchanan, was excluded from the count, and the second preference of each of his ballot papers was transferred, with the same effect as first preferences, to the candidate marked “2”.

This left four candidates in the count. If, at this point in the count, the cumulative total of one of the candidates continuing in the count had exceeded 50% of all ballots, that candidate would be declared elected.

That did not happen, so the continuing candidate with the fewest votes, Houlihan, was excluded. That led to the transfer of Houlihan’s ballots to the candidates marked as the next available preference.

Read more:

A matter of (mis)trust: why this election is posing problems for the media

When both Buchanan and Houlihan had been excluded and their ballots transferred, the third count was as follows:

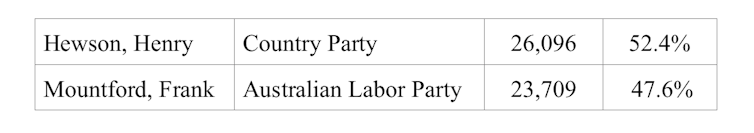

Because Barrie Armitage was now the lowest-polling candidate, he was excluded from the count, and his ballots were transferred to the two continuing candidates, according to the next available preference on each ballot. The final result was:

Because Barrie Armitage was now the lowest-polling candidate, he was excluded from the count, and his ballots were transferred to the two continuing candidates, according to the next available preference on each ballot. The final result was:

Note that the winning candidate is not necessarily the same as the candidate that received the most first preference votes. The preferential system ensures that the candidate elected is the one preferred by the majority in each electorate.

In the case of McMillan in 1972, Henry Hewson was the candidate preferred by the majority. The full details of this count can be found on the excellent Psephos website

In Australia, thanks to preferential voting, our House of Representatives members are each elected by an absolute majority of the voters in the electorate they represent.

Note that the winning candidate is not necessarily the same as the candidate that received the most first preference votes. The preferential system ensures that the candidate elected is the one preferred by the majority in each electorate.

In the case of McMillan in 1972, Henry Hewson was the candidate preferred by the majority. The full details of this count can be found on the excellent Psephos website

In Australia, thanks to preferential voting, our House of Representatives members are each elected by an absolute majority of the voters in the electorate they represent.

Authors: Stephen Morey, Senior Lecturer, Department of Languages and Linguistics, La Trobe University