Are you at risk of being diagnosed with gestational diabetes? It depends on where you live

- Written by Rae Thomas, Associate professor, Bond University

Sarah lives in London. She is pregnant with her first child. Her mother had gestational diabetes and Sarah is told this puts her into a higher risk category for the condition, thus she should have a test.

At 26 weeks, she has a 75g fasting glucose test to see if she has gestational diabetes. The test requires fasting, drinking the equivalent of two cans of soft drink, and takes several hours.

The next week her doctor tells her the initial fasting blood test showed a blood glucose level of 5.5 millimoles per litre (mmol/l), and that the two-hour level was 7.5mmol/l. This means she is under the cut-off and so not diagnosed with gestational diabetes. She is delighted.

Read more: How to rein in the widening disease definitions that label more healthy people as sick

Donna lives in Brisbane and is pregnant with her first child too. In Australia all women are tested for gestational diabetes and Donna is told to have a routine test for diabetes at 26 weeks.

She takes the same test which shows she has the same blood glucose level as Sarah. But because Donna lives in Australia she is diagnosed with gestational diabetes. Donna is devastated.

Donna was allocated a dedicated care provider when she was 15 weeks pregnant. But now she is considered “high risk” and is transferred to “standard care” where she has a different health provider every visit. She also has more medical appointments than before and sees a dietitian.

Since 2014, more Australian women have been diagnosed with gestational diabetes than in previous years and compared to women in other countries. But it’s not because they’re less healthy – it’s because the threshold for diagnosis has changed.

What is gestational diabetes?

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a diagnosis some pregnant women receive when they have elevated blood sugar (glucose) in pregnancy. A diagnosis can occur in several ways.

Some are diagnosed with diabetes while pregnant but have blood glucose levels high enough to be similar to diabetes diagnosed outside of pregnancy.

Some women diagnosed with gesational diabetes may still have lower blood sugar levels than those with diabetes who aren’t pregnant.

Echo Grid

Some women diagnosed with gesational diabetes may still have lower blood sugar levels than those with diabetes who aren’t pregnant.

Echo Grid

Others have glucose levels higher than normal and so are diagnosed with developing diabetes while pregnant but wouldn’t fulfil the usual criteria for diabetes if they weren’t pregnant. These two different women would be diagnosed with gestational diabetes.

Some women may have been diagnosed with diabetes before they were pregnant. These women would be diagnosed with pregestational diabetes.

These diagnostic pathways differ and the health risks to the mothers and babies diagnosed in these different pathways also differs, but all women are treated the same: their blood glucose levels are monitored and their diet restricted.

Why does gestational diabetes worry clinicians?

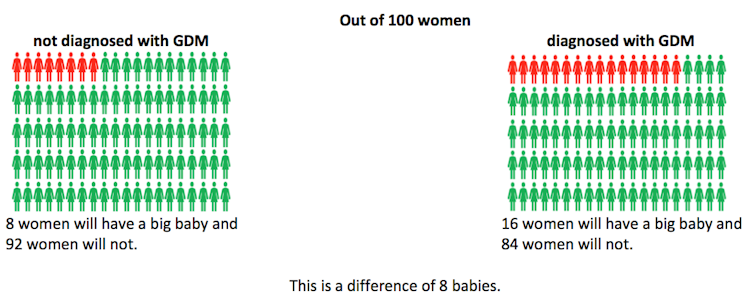

Several health problems can occur for mothers diagnosed with high glucose levels in pregnancy and their babies, including a higher risk of having a “big” baby. The average baby weighs just over 3kg but “big” babies are over the 90th percentile and weigh around 4kg.

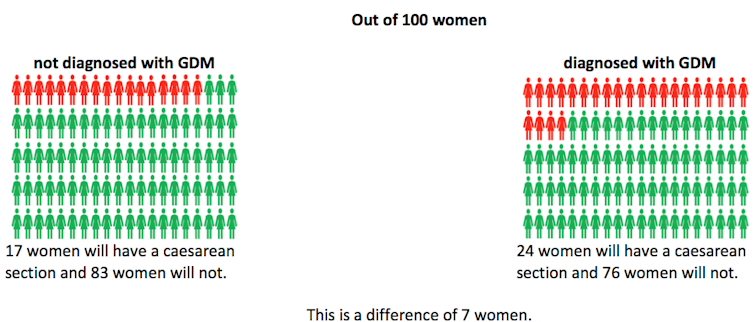

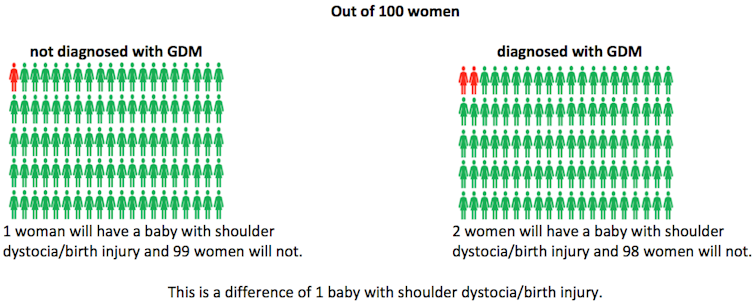

Other risks include having a pre-term delivery, having a cesarean section and babies having low glucose levels at birth. Rarely, babies can have a stuck shoulder during birth.

Chance of having a big baby

Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome study cohort., Author provided

Chance of having a cesarean section

Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome study cohort., Author provided

Chance of having a cesarean section

Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome study cohort, Author provided

Chance of the baby sustaining a shoulder or other birth injury

Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome study cohort, Author provided

Chance of the baby sustaining a shoulder or other birth injury

Shoulder dystocia is where one of the baby’s shoulders becomes stuck behind the mother’s pelvic bone during childbirth.

Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome study cohort, Author provided

Women diagnosed with gestational diabetes also often report feelings of self-blame, anxiety, confusion and stress of managing a new dietary regime.

Why is Donna diagnosed and not Sarah?

There is currently no internationally uniform definition of gestational diabetes. Experts disagree about the degree of glucose intolerance that poses a sufficiently increased risk to mother or baby.

A multinational study published in 2009 was supposed to clarify the uncertainty but the results showed that increased glucose levels were a continuous risk for poor outcomes in pregnancy. There was no clear cut-off; the more glucose intolerant, the more risk to mother and baby.

An international group recommended a cut-off but different countries have adopted different testing regimes and cut-offs.

In Australia, the diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes changed in 2014 with the aim to improve diagnostic accuracy and prevent harmful health outcomes for women and their babies.

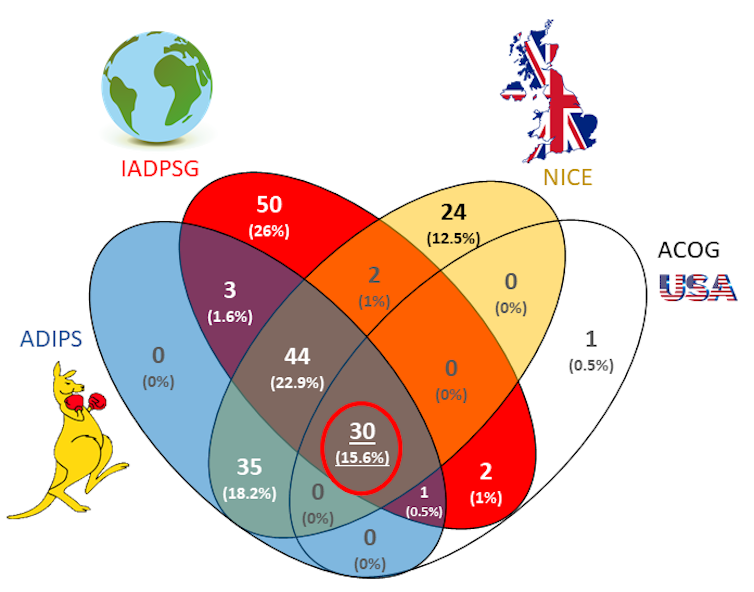

This figure shows you how complicated it is. The glucose results of 1,248 Brisbane women from the HAPO study were matched to four different international criteria for gestational diabetes. Although 191 women would have met one or more criteria, only 30 (15%) met criteria for all four.

Shoulder dystocia is where one of the baby’s shoulders becomes stuck behind the mother’s pelvic bone during childbirth.

Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome study cohort, Author provided

Women diagnosed with gestational diabetes also often report feelings of self-blame, anxiety, confusion and stress of managing a new dietary regime.

Why is Donna diagnosed and not Sarah?

There is currently no internationally uniform definition of gestational diabetes. Experts disagree about the degree of glucose intolerance that poses a sufficiently increased risk to mother or baby.

A multinational study published in 2009 was supposed to clarify the uncertainty but the results showed that increased glucose levels were a continuous risk for poor outcomes in pregnancy. There was no clear cut-off; the more glucose intolerant, the more risk to mother and baby.

An international group recommended a cut-off but different countries have adopted different testing regimes and cut-offs.

In Australia, the diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes changed in 2014 with the aim to improve diagnostic accuracy and prevent harmful health outcomes for women and their babies.

This figure shows you how complicated it is. The glucose results of 1,248 Brisbane women from the HAPO study were matched to four different international criteria for gestational diabetes. Although 191 women would have met one or more criteria, only 30 (15%) met criteria for all four.

Abbreviations: ADIPS Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society; IADPSG International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups; NICE National Institute for Clinical Excellence; ACOG American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Adapted from McIntyre HD, Gibbons KS, Lowe J, Oats JJN. Colour and pictures added., CC BY-NC-ND

Testing processes can also differ. Australia has universal screening, with a one-step process where all women have a test for diabetes, and those who test positive are diagnosed.

New Zealand has a two-step confirmatory process where women who test positive on an initial test (around 25% of women) go onto have a second confirmatory test. Only women with a positive result in the second test are diagnosed with gestational diabetes.

In some countries, such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, only women with at least one risk factor for gestational diabetes will be offered testing.

Rising rates in Australia

Rates of gestational diabetes diagnoses in Australia have increased from 2% in 1990 to nearly 14% in 2017.

Some of this is due to the increasing age of women becoming pregnant, more women being overweight, more testing, and better recording. But much of the rise has occurred since 2014 when the Australian definition changed.

Read more:

Weight gain during pregnancy: how much is too much?

The percentage of women diagnosed with gestational diabetes in Mackay in Far North Queensland increased from 9.8% to 19.6% in the first year of the change.

In a Melbourne hospital, researchers found the percentage of women diagnosed with gestational diabetes increased from 5.9% in 2014 under the old criteria, to 10.3% in 2016 under the new criteria.

In both studies, there was little to no change in health outcomes for mothers or babies.

Abbreviations: ADIPS Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society; IADPSG International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups; NICE National Institute for Clinical Excellence; ACOG American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Adapted from McIntyre HD, Gibbons KS, Lowe J, Oats JJN. Colour and pictures added., CC BY-NC-ND

Testing processes can also differ. Australia has universal screening, with a one-step process where all women have a test for diabetes, and those who test positive are diagnosed.

New Zealand has a two-step confirmatory process where women who test positive on an initial test (around 25% of women) go onto have a second confirmatory test. Only women with a positive result in the second test are diagnosed with gestational diabetes.

In some countries, such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, only women with at least one risk factor for gestational diabetes will be offered testing.

Rising rates in Australia

Rates of gestational diabetes diagnoses in Australia have increased from 2% in 1990 to nearly 14% in 2017.

Some of this is due to the increasing age of women becoming pregnant, more women being overweight, more testing, and better recording. But much of the rise has occurred since 2014 when the Australian definition changed.

Read more:

Weight gain during pregnancy: how much is too much?

The percentage of women diagnosed with gestational diabetes in Mackay in Far North Queensland increased from 9.8% to 19.6% in the first year of the change.

In a Melbourne hospital, researchers found the percentage of women diagnosed with gestational diabetes increased from 5.9% in 2014 under the old criteria, to 10.3% in 2016 under the new criteria.

In both studies, there was little to no change in health outcomes for mothers or babies.

A diagnosis depends, at least in part, on where you live.

Adi Saputra

So although there were significant increases in the number of women diagnosed with gestational diabetes, there are seemingly negligible health benefits.

However there were substantial health care costs. The Melbourne hospital above spent A$560,000 more caring for the additional women diagnosed with gestational diabetes under the criteria change.

Applying the same formula to the Australian population data, we estimate the net increase in Australian health costs due to the change in gestational diabetes criteria to be around A$28 million per year.

Guidelines and clinical practices are often revisited every two to five years, especially when there is emerging evidence of benefits or harms. It’s time to review how we define gestational diabetes and the impact on women, their babies and the Australian health system.

Read more:

The risks associated with gestational diabetes don't end after pregnancy

A diagnosis depends, at least in part, on where you live.

Adi Saputra

So although there were significant increases in the number of women diagnosed with gestational diabetes, there are seemingly negligible health benefits.

However there were substantial health care costs. The Melbourne hospital above spent A$560,000 more caring for the additional women diagnosed with gestational diabetes under the criteria change.

Applying the same formula to the Australian population data, we estimate the net increase in Australian health costs due to the change in gestational diabetes criteria to be around A$28 million per year.

Guidelines and clinical practices are often revisited every two to five years, especially when there is emerging evidence of benefits or harms. It’s time to review how we define gestational diabetes and the impact on women, their babies and the Australian health system.

Read more:

The risks associated with gestational diabetes don't end after pregnancy

Authors: Rae Thomas, Associate professor, Bond University