Mary Jane Cain, land rights activist, matriarch and community builder

- Written by Heidi Norman, Professor, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney

For the communities of Coonabarabran in New South Wales and her grasslands Gomeroi people, Mary Jane Cain is a revered figure. Cain lived from 1844 to 1929. In the late 1880s, she successfully advocated for Aboriginal land security – a rare coup for an Aboriginal woman at the time. In 1920, she penned a 23-page manuscript detailing her life, her observations of new land owners and their workers, and a list of Gomeroi words.

She was born when frontier violence was at its zenith. Decades long guerrilla warfare had raged as the Gomeroi people resisted pastoral invasion and violent recriminations. Some estimate as few as 10% of the Aboriginal populations survived these killing times.

Mary Jane Cain’s mother, Jinnie Griffin, a “full blood” whose life likely spanned pre and post-contact, had married an Irishman, Eugene Griffin. They moved between Mudgee and Coonabarabran where they operated, for a time, as travelling sales people. After being held up by bushrangers, they spent decades working on pastoral runs – Jinnie as a shepherd and Eugene as a dairyman. At the time of Mary Jane’s birth, they’d been working on Toorawindi property for some years.

The advent of gold mining in 1852 marked a significant shift on the pastoral frontier. As Cain wrote in her 1920 manuscript, all the white people working on one station “left to go mining”. Renewed interest in Aboriginal people as shepherds and stock workers contributed to an easing in frontier violence on Gomeroi lands. This created opportunities for Aboriginal families to get back to their country, but in very different circumstances – as workers, generally without pay.

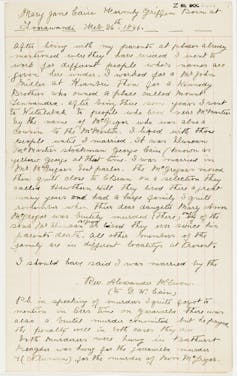

A page of Mary Jane Cain’s hand written manuscript.

State Library of NSW.

A page of Mary Jane Cain’s hand written manuscript.

State Library of NSW.

By the 1880s Cain had begun agitating for Aboriginal land rights. The 1890s depression caused a further wave of displacement of Aboriginal workers. In this context, the Aboriginal Protection Board emerged, partly in response to rising numbers of Aboriginal people now relegated to the fringes of towns. The board introduced ways to control Aboriginal populations including containment on reserves.

Mary Jane had married Aboriginal stockman Joe Cain in 1865 at Weetalabah station, where they were both living and working, in the home’s “best parlour”. By the 1880s she was living closer to town and shepherded her goats to the mountains and back each day. Her husband Joe became unwell and as she wrote to the Crown, she needed to secure land to support him and her nine children. She petitioned for land at Forky Mountain, about six miles from Coonabarabran, where she could run her goats.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Ruby Lindsay, one of Australia's first female graphic designers

The politics of land

In February 1892, Cain secured 400 acres. Further land grants in 1902, 1906 and 1911 saw her recover 600 acres that became home to displaced Aboriginal families up until the late 1950s. These families made homes from kerosene tins lined with glued sheets of newspaper, grew vegies, milked their cows, hosted pantomimes and lived lives recalled with enormous fondness. Over this site, Mary Jane Cain was Queen.

Cain’s grandchildren all recalled “multiple letters” from Cain addressed “to the Queen” (Victoria) requesting the land at Forky Mountain and her trips to Sydney to meet with government officials to petition for her land. Her descendants emphasised that Queen Victoria granted Cain land to manage as a place “for the dark people to live on”.

Mary Jane Cain, right, and grandsons George and James.

The sun dancin' : people and place in Coonabarabran (Aboriginal Studies Press, 1994).

Mary Jane Cain, right, and grandsons George and James.

The sun dancin' : people and place in Coonabarabran (Aboriginal Studies Press, 1994).

While Aboriginal reserves and missions are often viewed as sites of segregation and genocidal violence, Mary Jane Cain’s story highlights the economic, social and political context that saw reserves, at least initially, self-selected and defended by Aboriginal families; where Aboriginal worlds survived and where political organisation occurred.

In NSW, of the 85 Aboriginal reserves created in the period 1885 to 1895 more than half (47) were initiated by Aboriginal families. The new interest in taking up reserves coincided with a downturn in the two dominant economies – pastoralism and gold mining. Land likely represented an option for Aboriginal security in the wake of decades of colonial violence and disease that caused loss of land, people and livelihood.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Elsie Masson, photographer, writer, intrepid traveller

‘Queen Mary Jane’

Cain’s grandchildren, Julia and Violet Robinson, Ethel Sutherland, Joe Cain and Emily Chatfield share generous and proud stories of “Queen” Mary Jane: she was a great cook, hand stitched marvellous outfits from hessian and old sugar bags and ran a large, immaculately scrubbed, loving home.

They loved her dearly and worked hard to fetch her goats from the mountains; they say she dressed beautifully and descriptions of her “sharp features” suggest they thought her beautiful. She was generous and kind, loaned money to those in need, and welcomed all to Burra Bee Dee (as the Aboriginal reserve was known from 1912). She was Queen of the reserve and Queen in the eyes of her family.

“Queen” was clearly a title Mary Jane was comfortable with: her 1920 manuscript is annotated at page 23 “by M.J. Cain, Queen 1920”. Available studio photos show a regal figure and flanked by her grandsons in military uniform, her own clothing and stature match this formal authority.

Visiting missionaries to Burra Bee Dee in 1909 were also reminded and duly acknowledged her Queen status. They fondly reported on the performances, poetry recital, dancing and the singing, at the end of a long evening, of God Save the King. Mary Jane Cain implored a further and final recital in her honour: God Save the Queen. They obliged.

She also held a powerful place in white society. After her death in 1929, the Coonabarabran Times described Mary Jane as being,

known and loved by all from a very great distance round this district and outside it … and a word against her, … would have evoked the undying hostility from the oldest and most respected families of the North Western slopes and Central West.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Hop Lin Jong, a Chinese immigrant in the early days of White Australia

Cain’s keen sense of justice is evident in one entry in her 1920 manuscript where she refers to organising a petition in 1864 “which everyone signed” in defence of two brothers and “a young [‘half caste’] man … whom they hired” who had been wrongly arrested and charged for cattle stealing.

She writes that: “I presented the petition to Thomas Gordon Danger who was at that time member of Parliament”, which had the effect of reducing their sentence and “them liberated at five years”.

Mary Jane Cain Bridge over the Castlereagh River in NSW.

Wikimedia Commons

Mary Jane Cain Bridge over the Castlereagh River in NSW.

Wikimedia Commons

Aboriginal people negotiated the rapid change to their worlds as the grasslands country came to be intensively farmed. At Burra Bee Dee and through the oral history of Mary Jane Cain’s descendants we hear the stories of matriarchs who acquired the skills of the new world – literacy, shepherding and stock work, knowledge of political systems and how to effect change – and who built ways to sustain Aboriginal worlds in dramatically altered circumstances.

Today, after several years of careful community work, the history of Burra Bee Dee is beautifully documented with signage and photos detailing where families lived. The adjacent cemetery is a site of return for many generations to come. The bridge over the Castlereagh river bears Mary Jane’s name, the local rotary club has installed a plaque in her honour and her life has inspired an art exhibition. Still, the story of this matriarch and queen to her people deserves to be more widely told.

Professor Heidi Norman is a descendant of the Gomeroi people. Her Nan’s uncle (Charles Ruttley) married Mary Jane’s daughter (Eliza Josephine).

Authors: Heidi Norman, Professor, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney