100 years later, why don't we commemorate the victims and heroes of "Spanish flu"?

- Written by Peter Hobbins, ARC DECRA Fellow, University of Sydney

At Sydney’s enormous Rookwood Cemetery, a lichen-spotted headstone captures a family’s double burden of grief.

The grave contains the remains of 19-year-old Harriet Ann Ottaway, who died on 2 July 1919. Its monument also commemorates her brother Henry James Ottaway, who “died of wounds in Belgium, 23rd Sept 1917, aged 21 years”.

While Henry was killed at the infamous Battle of Passchendaele, Harriet’s headstone makes no mention of her own courageous combat with “Spanish flu”.

Harriet’s story typifies the enduring public silence around the pneumonic influenza pandemic of 1918–19. Worldwide, it killed an estimated 50-100 million people – at least three times all of the deaths caused by the First World War.

Read more: Why historians ignored the Spanish flu

After the disease came ashore in January 1919, about a third of all Australians were infected and the flu left nearly 15,000 dead in under a year. Those figures match the average annual death rate for the Australian Imperial Force throughout 1914–18.

Arguably, we could consider 1919 as another year of war, albeit against a new enemy. Indeed, the typical victims had similar profiles: fit, young adults aged 20-40. The major difference was that in 1919, women like Harriet formed a significant proportion of the casualties.

Read more: World politics explainer: The Great War (WWI)

Deadly flu spread rapidly

There was no doubt about the medical and social impact of the “Spanish flu”. Although its origins remain contested, it certainly didn’t arise in Spain. What is known is that by early 1918, a highly infectious respiratory disease, caused by a then-unknown agent, was moving rapidly across Europe and the United States. By the middle of that year, as the war was reaching a tipping point, it had spread to Africa, India and Asia.

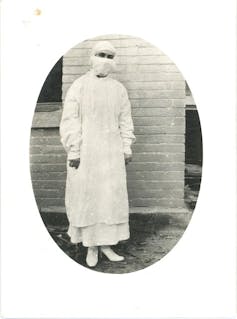

About a third of the entire world’s population was infected with Spanish flu.

Macleay Museum, Author provided

About a third of the entire world’s population was infected with Spanish flu.

Macleay Museum, Author provided

It also took on a much deadlier profile. While victims initially suffered the typical signs and symptoms of influenza – including aches, fever, coughing and an overwhelming weariness – a frighteningly high proportion went rapidly downhill.

Patients’ lungs filled with fluid – which is why it became known as “pneumonic influenza” – and they struggled to breathe. For nurses and doctors, a tell-tale sign of impending death was a blue, plum or mahogany colour in the victim’s cheeks.

This, sadly, was the fate of young Harriet Ottaway. Having nursed a dying aunt through early 1919, in June she tended her married sister Lillian, who had come down with pneumonic influenza.

Despite taking the recommended precautions, Harriet contracted the infection and died in hospital. Ironically, Lillian survived. But in the space of less than two years she had lost both a brother to the Great War and her younger sister to the Spanish flu.

An intimate impact worldwide

Indeed, as Harriet’s headstone reminds us, this was an intimate pandemic. The statistics can seem overwhelming until you realise what it means that about a third of the entire world’s population was infected.

Whatever your heritage, your ancestors and their communities were almost certainly touched by the disease. It’s a part of all of our family histories and many local histories.

Read more: How infectious diseases have shaped our culture, habits and language

It wasn’t just victims who were affected. Across Australia, regulations intended to reduce the spread and impact of the pandemic caused profound disruption. The nation’s quarantine system held back the flu for several months, meaning that a less deadly version came ashore in 1919.

But it caused delay and resentment for the 180,000 soldiers, nurses and partners who returned home by sea that year.

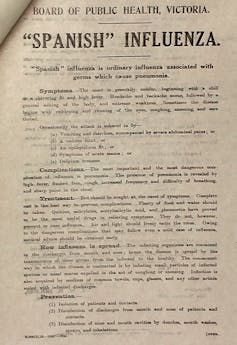

Leaflets like this one from Victoria tried to warn people of the dangers of Spanish flu.

Board of Public Health, Victoria/Public Records Office of Victoria

Leaflets like this one from Victoria tried to warn people of the dangers of Spanish flu.

Board of Public Health, Victoria/Public Records Office of Victoria

Responses within Australia varied from state to state but the crisis often led to the closure of schools, churches, theatres, pubs, race meetings and agricultural shows, plus the delay of victory celebrations.

The result was not only economic hardship, but significant interruptions in education, entertainment, travel, shopping and worship. The funeral business boomed, however, as the nation’s annual death rate went up by approximately 25%.

Yet for some reason, the silence of Harriet’s headstone is repeated across the country. Compared with the Anzac memorials that peppered our towns and suburbs in the decades after the Great War, few monuments mark the impact of pneumonic influenza.

Nevertheless, its stories of suffering and sacrifice have been perpetuated in other ways, especially within family and community memories. A century later, these stories deserve to be researched and commemorated.

Read more: Speaking with: Peter Doherty about infectious disease pandemics

Despite the disruption, fear and substantial personal risk posed by the flu, tens of thousands of ordinary Australians rose to the challenge. The wartime spirit of volunteering and community service saw church groups, civic leaders, council workers, teachers, nurses and organisations such as the Red Cross step up.

They staffed relief depots and emergency hospitals, delivered comforts from pyjamas to soup, and cared for victims who were critically ill or convalescent. A substantial proportion of these courageous carers were women, at a time when many were being commanded to hand back their wartime jobs to returning servicemen.

In resurrecting stories such as the sad tale of Harriet Ottaway, it’s time to restore our memories of the “Spanish flu” and commemorate how our community came together to battle this unprecedented public crisis.

Authors: Peter Hobbins, ARC DECRA Fellow, University of Sydney