As the High Court challenge to abortion clinic 'safe access zones' begins, there is much at stake

- Written by Tania Penovic, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law and Deputy Director, Castan Centre for Human Rights Law, Monash University

From October 9-11, the High Court of Australia will hear a challenge to the constitutional validity of Victorian and Tasmanian legalisation that provides for “safe access zones” around abortion clinics.

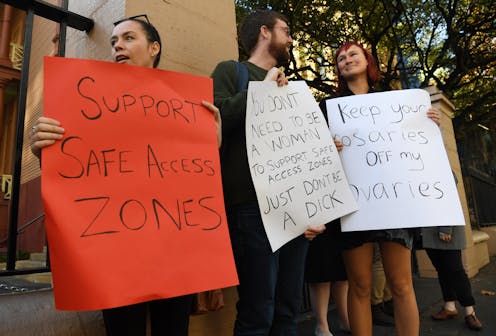

Safe access zones are sometimes called “bubble zones” because they create a bubble around abortion clinics. In Victoria and Tasmania, safe access zones are the area within a 150 metre radius of a clinic. Within these zones, certain conduct is prohibited, including the harassment of people accessing the clinic.

The purpose of safe access zones is to prevent patients, staff and others from being targeted by anti-abortion protesters. These laws are designed to protect the safety, well-being, privacy and dignity of people attending abortion clinics, and facilitate women’s access to health services without harassment and intimidation.

Read more: Explainer: what are abortion clinic safe-access zones and where do they exist in Australia?

Safe access zones now operate in Tasmania, Victoria, the ACT, the Northern Territory and New South Wales. A bill that establishes safe access zones is currently before the Queensland Parliament.

These laws do not prevent anti-abortion protesters from expressing their views. They can write to newspapers and politicians, and protest in other places. The only thing these laws prevent them from doing is protesting within a safe access zone.

Background to the cases

The laws that have been challenged in the High Court are those that operate in Victoria and Tasmania. The High Court will hear these two challenges together.

Kathleen Clubb is an active member of the US-founded anti-abortion group known as Helpers of God’s Precious Infants. Members of this group have protested outside East Melbourne’s Fertility Control Clinic six days a week for more than 20 years. In October 2017, Clubb was found guilty of “prohibited behaviour” within the safe access zone outside the Fertility Control Clinic. She was found to have engaged in communication about abortions which is reasonably likely to cause anxiety or distress.

Similarly, John Graham Preston was found guilty of engaging in prohibited conduct after protesting within the safe access zone outside Hobart’s Specialist Gynaecology Centre in July 2016.

Clubb and Preston are now challenging the constitutional validity of safe access zone legislation before the High Court. They argue that parts of the Victorian and Tasmanian safe access zone laws, respectively, are invalid on the basis that they violate the implied freedom of political communication under the Australian Constitution.

What is freedom of political communication?

Unlike the right to free speech under the US Constitution, the freedom of political communication under the Australian constitution is narrower. It only protects communication that is “political” – in other words, communication about political matters and representative government. Our High Court has taken a broad view of what amounts to political communication.

Further, unlike the US, freedom of political communication doesn’t act as a “trump card”, or an inviolable right. Laws can limit political communication in some circumstances, such as where the law is designed to protect public safety.

In the Clubb and Preston cases, the High Court will decide whether parts of the safe access zone laws limit political communication and if so, whether the limit is justified.

We argue that if the laws do limit political communication, they do so only to the extent necessary to protect the safety, privacy, well-being and dignity of patients and staff. Therefore, safe access zone laws permissibly limit political communication.

What is at stake?

The Victorian and Tasmanian laws protect people from unwelcome intrusions into their privacy by strangers who seek to interfere in deeply personal decisions.

In research undertaken over the past 18 months, we have looked at the impact of anti-abortion protests outside clinics and what has changed since safe access zones were established.

Anti-abortion protests outside clinics have included a range of unwelcome behaviour. This includes verbal abuse and the display of violent images. It has also included chasing women seeking access to clinics and barring access to clinic entrances.

Read more: Where Australian states are up to in decriminalising abortion

The impact of this behaviour is devastating for some patients and staff. We were told that the protesters created an undercurrent of anxiety and fear. Many women were extremely traumatised by the protests and needed additional medical care.

Health professionals told us that the protesters’ conduct has had an especially harmful effect on young women and those who had experienced sexual or physical violence. We have learned that protesters have deterred some women from seeking abortions and follow-up care.

Safe access zones have not stopped anti-abortion protests. These protests have continued outside safe access zones. But they have prevented the protesters from targeting individuals. If the laws are found to be constitutionally invalid, the targeting of women will resume.

The purpose of safe access zones is to protect the safety, privacy and dignity of people accessing clinics that provide lawful healthcare services. Because of the importance of their purpose we are hopeful the High Court will find these laws compatible with the Constitution.

The authors prepared written submissions in the Clubb proceeding on behalf of the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law seeking leave to appear as amicus curiae. The centre was granted leave with respect to those submissions.

Authors: Tania Penovic, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law and Deputy Director, Castan Centre for Human Rights Law, Monash University