The Tale of Genji, a 1,000-year-old Japanese masterpiece

- Written by Rebecca Hausler, PHD Candidate and Researcher in Japanese Studies, School of Languages and Cultures, The University of Queensland

In our series, Guide to the classics, experts explain key works of literature.

Celebrating its millennial anniversary in 2008, The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari) is a masterpiece of Japanese literature. Completed in the early 11th century, Murasaki Shikibu’s elegant and enchanting prose spans 54 chapters, features some 400 characters and contains almost 800 separate poems. Many consider it to be the world’s first novel, predating most European texts by several hundred years.

Murasaki Shikibu transformed her experiences of courtier life into an intricate narrative fusing fiction, history and poetry. This blending of forms defies simple categorisation under any one genre, though the striking interior life of its characters has led many to term it a psychological novel with prose that feels distinctively modern.

Captivating readers across the English-speaking world from the early 20th century onwards, she has often been compared to canonical artists such as Marcel Proust or Jane Austin for her ability to convey the splendour in the ordinary to her audience.

Consider this passage where a remorseful Genji seeks redemption from his deceased father for his misdeeds against him:

Coming to the grave, Genji almost thought he could see his father before him. Power and position were nothing once a man was gone. He wept and silently told his story, but there came no answer, no judgment upon it. (Chapter 12)

This beautifully captures both the infinite tragedy of losing a loved one, and the abyss of guilt that such unresolved conflicts inevitably impart on us. These words are just as poignant today as they would have been 1,000 years ago.

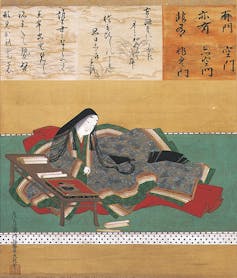

A 17th-century portrait of Murasaki Shikibu, author of The Tale of Genji.

Wikimedia

A 17th-century portrait of Murasaki Shikibu, author of The Tale of Genji.

Wikimedia

The author served Empress Shōshi in the Imperial court of Heian (794-1185), situated in modern-day Kyoto. Courtiers were often referred to only by rank, and women were usually known only in relation to their husbands, sons or fathers. Due to such customs her actual name is unknown. Thus Murasaki Shikibu was likely gifted this moniker by her readers; “Murasaki” after the story’s heroine, and “Shikibu” referring to her father’s ministerial position within the court.

Her father, Fujiwara no Tametoki, was a scholar of Chinese classic literature. Despite Chinese being a masculine genre of writing, he nourished his daughter’s keen interest and special talent for it, as well as the more traditionally Japanese feminine writing styles of waka, essays, diary and letters (kana).

Read more: Why you should read China's vast, 18th century novel, Dream of the Red Chamber

Scandal in the court

The Tale of Genji weaves a vivid depiction of aristocratic life in Heian Japan, which centres on the amorous exploits and political gameplay of the nobility. The titular “Shining” Genji is devastatingly handsome, with smooth-as-silk charisma, and a litany of musical, literary and academic skills that “to recount all his virtues would, I fear, give rise to a suspicion that I distort the truth” (Chapter 1).

Throughout the tale, however, he is revealed as an enigmatic but ultimately flawed hero. Rising to the rank of Honorary Retired Emperor (despite never actually reigning), the story of Genji’s success is a multigenerational saga filled with passion, deceit, jealousy, great rivalries and also great intimacies.

A scene from The Tale of Genji painted in the 11th century.

Wikimedia

A scene from The Tale of Genji painted in the 11th century.

Wikimedia

Potential readers should be forewarned, however, that many of Genji’s amorous conquests are likely to raise an eyebrow with contemporary audiences. Genji kidnaps and grooms a ten-year-old child bride, before fathering a secret love-child with his stepmother, all the while insistently pursuing a plethora of women in various extramarital affairs.

In a post-#metoo world, it is perhaps difficult to see Genji’s actions as anything but deplorable; however, by Heian standards Genji is lauded as a venerable hero. Controversial themes, including rape, have been condemned by contemporary readings. But the text allows and even encourages many different readings (for example in feminist and parodic fashions), presenting a challenge for contemporary readers and translators alike.

The challenge of translating Genji

The original Genji text in Japanese poses a number of issues for modern-day readers. Characters were rarely assigned proper names, with designations implied by way of their titles, honorific language, or even the verb form used. The writing also relies heavily on the reader’s pre-existing understanding of courtier life, poetry and history, which is often beyond the contemporary recreational reader.

The first complete English translation was published between 1925 and 1933 by esteemed orientalist scholar and translator Arthur Waley (who translated many other Chinese and Japanese texts such as Monkey and The Pillow Book). Waley’s translation prompted strong reactions from Japanese authors such as Akiko Yosano and Jun’ichirō Tanizaki. Both subsequently completed multiple translations of the work into contemporary Japanese (Yosano’s last translation was in 1939, with Tanazaki’s editions spanning 1939-1965).

There have been a number of recent translations in English, modern Japanese and several other European and Asian languages. Royall Tyler’s 2003 translation provides substantial footnotes, endnotes, illustrations and maps, which offer thorough explanations of the nuances of the text. This makes it suitable for novices as well as the academic reader.

The attention The Tale of Genji has received from translators in recent years speaks not only to the challenges in its translation but also to the beauty and importance of the work itself.

The Japanese celebration of cherry blossoms is an example of ‘mono no aware’, reflecting the tragic fleetingness of beauty.

Shutterstock

The Japanese celebration of cherry blossoms is an example of ‘mono no aware’, reflecting the tragic fleetingness of beauty.

Shutterstock

Read more: How Conrad’s imperial horror story Heart of Darkness resonates with our globalised times

Allure across time

The Tale of Genji is steeped in exquisite images of nature and heavily laden with tanka-style poetry. Descriptions of autumn leaves, the wailing of insects, or the subtle light of the moon work to heighten the complex and nuanced emotions of Murasaki Shikibu’s elegant characters as they traverse the difficult landscape of love, sex and the politics of court life. Such poetic language played a very important role in the communications and rituals of Heian courtier society.

The term mono no aware is often used when discussing The Tale of Genji. This somewhat untranslatable phrase portrays the beautiful yet tragic fleetingness of life. It has deep connections to Buddhist philosophies, emphasising the impermanence of things.

The Japanese celebration of the falling of the cherry blossoms is a good example of mono no aware. Murasaki’s poignant references to the natural world saturate the text and help us reflect on the illusory and sometimes unexplainable nature of life, love and loss.

As a counterbalance to such exquisite imagery, Genji also explores dark and divisive elements. Apart from familial sex, polygyny and sexualisation of children, it includes several key scenes of women experiencing spirit possession or mono no ke. These scenes depict women acting in strange and unpredictable fashions, and suggest that possession actually caused women to become ill and die.

These examples are just a taste of the vast subject matter and textual richness that The Tale of Genji offers readers. Adaptations, parodies and sequels have seen the tale reimagined into film, noh theatre, opera, manga and art. Genji is still very much alive.

Authors: Rebecca Hausler, PHD Candidate and Researcher in Japanese Studies, School of Languages and Cultures, The University of Queensland