a strikingly prescient morality tale about banking

- Written by Julian Meyrick, Professor of Creative Arts, Flinders University

In our Great Australian Plays series, we nominate the best of Australian drama.

There is no single event foreshadowing the darker mood of the 1980s, as the election of the Whitlam Labor government presaged the expansive atmosphere of the 1970s. Margaret Thatcher, “the Iron Lady”, became UK Prime Minister in 1979. The neo-conservative Ronald Reagan was elected US President in 1981. Thereafter came a firestorm of social and economic changes: the deregulation of financial markets; the rise of Islamic fundamentalism; the dismantling of trade barriers; the collapse of Eastern bloc communism; the re-opening of China to the West; Fukuyama’s End of History.

No one could accuse 1970s Australian drama of being simplistic or trouble-free. But its spirit is rambunctious. Its love affair with the popular theatre of the past ensures that even its most serious offerings have a bright and breezy feel. This quality disappears entirely in the 1980s, to be replaced by a grim preoccupation, a tonal umbra flecked with fury, phantasmagoria and perturbation. Realism and anti-realism – the two stalwarts of our play classification system thus far – writhe in their genre categories, as if possessed by an alien intelligence. Individual plays of the period are neither one style nor the other, or both simultaneously, or a new, disturbing mutation.

Read more: When the cultural cringe abated: Australian drama in the 1970s

In the 1980s, people held their breath, waiting to see if nuclear conflict would reduce the planet to atomic dust. There is a similar feel to its drama, a muted despair and a latent fear.

Stephen Sewell’s Dreams in an Empty City (1986) was written in the middle of the decade and exemplifies these traits. It is apocalyptic in feel, epic in scope and unforgiving in length. A so-called “state of the nation” play, it is eager to tackle big ideas and problems, and unapologetic about the resulting speechifying. It is political drama at its most thrilling and perilous. Hence it’s now-to-us obvious topic: international banking.

How little has changed

When I selected Sewell’s play for this series, in December last year, Australian banks were in the media spotlight for manipulation of the benchmark bill swap rate. Now their immoral behaviour is the focus of a full-blown Royal Commission. Dreams in an Empty City was thus a drama ahead of its time. In 1986, the banks had not yet achieved the general repugnance and distrust they now lay claim to. Or perhaps Sewell recognized the age we have been living in all the while. It points to how little has really changed in 32 years that the play might have been written last week.

Read more: Evidence from the banking royal commission looks like history repeating itself

Its complicated plot defies detailed summary. Three main storylines can be identified, which wind in and out of each other like a knot garden. The first is a high-stakes feud between Simon Wilson, an ageing, silver-tail financier, and Derek Wiesland, an uncouth, criminal billionaire of the sort Australia regularly produces. This narrative, which has a number of subplots to it, is one in which two men attempt to destroy each other for strictly business reasons, thus demonstrating, in Wilson’s words, “moral death, the capacity for passionless violence, the terror of meaningless”. (Dreams is exceedingly existential in some of its dialogue).

The second storyline revolves around an ex-priest-turned-actor, Chris O’Brian, who discovers there is a contract out on his life. Chris is the emotional heart of the action. Renouncing pre-emptive violence, yet refusing to run, he has no choice but to await his fate and try to find out the reason for it. He lives with Karen, a one-time socialist, and many of their conversations involve a lugubrious thrashing-through of ethical questions, both personal and political. Chris is starring in a play where he is a South American priest caught up in a scenario of self-sacrifice and redemption. (Dreams eschews light irony in favour of full-strength symbolism).

As it turns out, Chris himself is also looking for redemption: for a murder he committed years previously in Thailand. The skeletal hand of the past is felt everywhere in Sewell’s play, reminding audiences of Karl Marx’s famous saying that “the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living”. (You can watch part of a major speech by Chris performed by a young actor here).

The third and final storyline is about banking itself. At its centre is Interbank Australia, a subsidiary of an American investment firm so large that if were to fail, it would crash the banking system and the economy around it (sound familiar?). Interbank’s biggest debtor is Derek Wiesland, who it discovers has been inflating the value of his property portfolio in order to borrow more money, in order to buy more property, in order to borrow more money… etc.

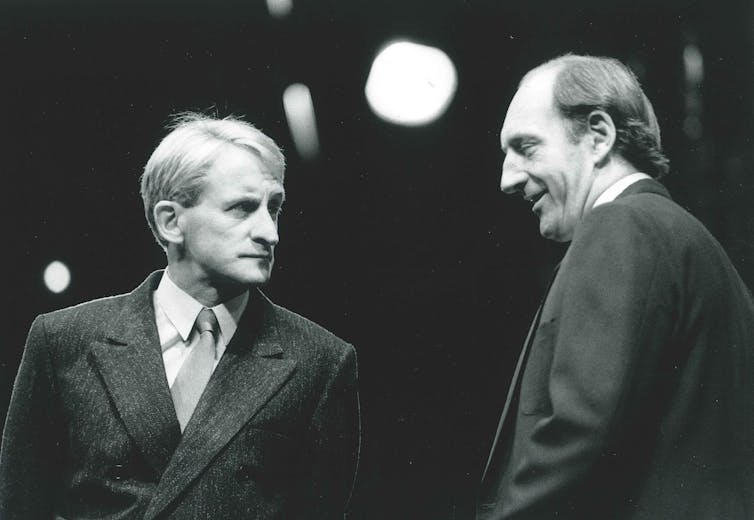

John Gaden as Wilson and Warwick Moss as Wiesland in the 1986 production.

David Wilson

John Gaden as Wilson and Warwick Moss as Wiesland in the 1986 production.

David Wilson

Instead of being contrite, Wiesland, a potty-mouthed thug with no time for bankers’ hypocrisies, insists his debt is Interbank’s problem, and it should buy back his buildings on terms favourable to him. As it turns out, Interbank has no choice but to do this, because the US company who own them is going down the gurgler thanks to their own poor loan strategy (familiar again?).

Thus a foul and insolvent entrepreneur is propped up by a duplicitous bank. Between them, they decide there is only one way out of their dilemma – to heat up the Australian property market, attract mums-and-dads investors, and pass on their losses to them.

What brings these three storylines to the point of convergence is a decision by Chris’s brother, Mark, who ran the O’Brian family building company before it was taken over by Wiesland, to reveal to Wilson the extent of Wiesland’s debts. The three men are thus feloniously linked. Some months previously, Wilson set up an offshore tax fraud scheme for Wiesland – Caracalla Ltd – which Mark abetted, secretly putting Chris’s name on company deeds.

Chris’s murder is necessary to either hush him up, lest the tax fraud scheme be exposed, or revenge Mark’s betrayal of an unforgiving employer. Whichever way, Chris is a dead man, and for no other reason, ultimately, than the people around him are totally corrupt. The name Caracalla, it is revealed, is taken from the Roman Emperor who killed his brother to gain power, and then destroyed all images of him, to hide his crime.

Money and morality

The dialogue of Dreams in an Empty City is as layered as its narrative, and deftly switches between different registers. The two most important are talk about money, and talk about morality. In respect of the first, Sewell shows an astounding ability to parse the language of banking and present it to audiences in such a way that its complexity is acknowledged, even as its consequences are rendered accessible.

Stephen Sewell has an astounding ability to parse the language of banking.

Maja Baska NIDA

Stephen Sewell has an astounding ability to parse the language of banking.

Maja Baska NIDA

Here, for example, is Interbank Australia’s floor manager, Harry (a good American) chatting to a friend he runs into at an Embassy dinner. It’s early in the play, before trouble starts:

George: What kind of loan policy you got?

Harry: I’m not in loans but I think it’s the same policy as back home: energy and real estate.

George: So what sent Continental to the wall?

Harry: They were cowboys. You could tell ‘em you had an oil well in your wisdom tooth and they’d give you a loan.

George: Al reckons International was up to the same thing.

Harry: No. I don’t believe it. There was something else.

George: What?

Harry: (after a slight pause) The bastards were into tax avoidance – the same thing Chase was up to.

George: What Cayman Islands?

Harry: Yeah, the works.

George: You blow the whistle on them?

Harry: I took it as far as I could.

George: So you end up here.

Harry: In a word, yes.

George: Tax avoidance – everyone’s in to it. You’d be a dope not to.

Harry: It’s wrong.

George: Why?

Harry: You and I end up paying for it – the ordinary people. When the government can’t afford to fix the roads, it’s not because we’re cheating on our tax.

George: For the roads – the bastards are paying defence contractors six hundred bucks for an ashtray. Don’t make me laugh, Harry: it’s crooked from the top down.

Sewell is a playwright who loves words. For state of the nation drama, less is not more. More is more. Dreams in an Empty City exudes verbal superfluity, a compulsion to give audiences in excess of what they paid for. This prolixity is not gratuitous, however, but is motivated by an obsessive desire to communicate. The play wears its heart on its sleeve, even as its story traverses strange intellectual and emotional pathways.

An example of the dialogue around morality comes at the end, when Wilson, who has engineered Chris’s death, offers to save him if he will agree to become his heir. Wilson is dying of cancer, and lost his only son years before. During the course of the play he befriends Chris, attracted to the ex-priest’s agonized integrity as necessary to a fully human existence. Being who he is, however, Wilson tries to lure Chris to his own debased view of life:

Wilson: Let me show you what I know! (He begins to pull the curtain aside) Let me show you the power of evil! The city, Chris; one of the most beautiful cities in the world. A city sprung from greed and ambition, built from human flesh, every building the grave of a labourer whose life was less important than the profit its construction meant. The city, Chris, thrown up by finance and speculation, conceived in bribery, corruption and murder. A sparkling, empty edifice of dreams and nightmares. Listen to it, Chris, listen to it sigh: listen to its misery, its glory, its hunger. Feel the hum as power flows through it, organizing it, animating it, connecting every part of it from the magnate in his penthouse to the single mother in her room. The city, Chris, the city of death glistening in the light of its own conceit…

If audiences discern echoes of Satan’s temptation of Jesus in the desert, they’d be correct. Dreams in an Empty City is saturated in Christian eschatological imagery; of blood, guilt, sacrifice, the beauty of innocence, the horror of sin and, ultimately and most importantly, the rejection of violence.

The dramatic use of religious symbolism is reminiscent of The Cake Man ten years prior. But whereas Robert Merritt blends Christianity and Dreamtime story, Sewell blends Christianity and modern economic and political theory.

Read more: The great Australian plays: The Cake Man and the Indigenous mission experience

The discombobulation is similar, but the dramatic results strikingly contrast. In mood and mode, The Cake Man is warm, elegiac and bittersweet. Dreams in an Empty City is as cold and bare as bones in a crypt. As Interbank’s manager Nat Boas (a bad American), admits at the end of the play, when asked why she has unscrupulously precipitated global financial collapse, “because banking’s the only industry that runs on trust, and bankers are the last people you should”.

A provocative statement in 1986. Today, more like the unvarnished truth.

Authors: Julian Meyrick, Professor of Creative Arts, Flinders University