Looking past the Gold Coast the world sees today

- Written by Andrew Leach, Wallace Fellow, Villa I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, and Professor of Architecture, University of Sydney

One of the most prominent images of the Commonwealth Games host city is of the bank of high-rise apartment buildings and hotels that loom over the beach of Surfers Paradise. Although the Games are taking place across the city, from its dense edge, past sprawling suburbs to its quasi-rural hinterland, one can be forgiven for conflating Surfers with the entire Gold Coast. More than anywhere else in Australia the Gold Coast hovers between being a traditional city and an urbanised territory — with all the stuff of a city but its density.

Frank Moorhouse once said the Gold Coast:

resembled a city that had been designed as an architect’s model of a high-rise city which had washed up on a stretch of beautiful beach where it grew magically into real dimensions.

There is something in this observation in each photograph taken of its most built-up moments.

A shiny new city masks a deep history

Surfers Paradise shares this apparent and sometimes odd superficiality with the holiday cities of Spain’s Costa del Sol and Florida’s Atlantic edge. Behind it, though, lies a deep history that has been written and overwritten in successive layers that have become thinner and thinner as time goes on.

Not far from the high-rises of Surfers Paradise is Kombumerri Park, in the canal estate of Broadbeach Waters. There, landscapers in 1965 discovered a burial site that had been in continual use from the eighth century to the colonial era, more than a millennium. It should surprise nobody that the waterways, swamps and arable land of Moreton Bay, on which the Gold Coast sits, sustained the region’s first people for tens of thousands of years before James Cook charted the coast in the 18th century.

Broadbeach and Lennons Broadbeach Hotel in 1960, five years before the discovery of an ancient burial ground at neighbouring Broadbeach Waters.

Photographer unknown. Gold Coast City Libraries Local Studies Collection, Author provided

Broadbeach and Lennons Broadbeach Hotel in 1960, five years before the discovery of an ancient burial ground at neighbouring Broadbeach Waters.

Photographer unknown. Gold Coast City Libraries Local Studies Collection, Author provided

But the Gold Coast as it stands today would seem vastly changed to anyone returning to the city after a mere ten years – in part a response to the massive task of hosting the Commonwealth Games, but largely because that is the pace of change here.

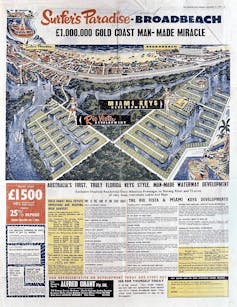

The announcement of Rio Vista and Miami Keys in The Courier Mail in 1957.

State Library of Queensland, Author provided

The announcement of Rio Vista and Miami Keys in The Courier Mail in 1957.

State Library of Queensland, Author provided

The Gold Coast was named as such in 1958. “South Coast” didn’t quite capture the ambitions of developers like Alfred Grant, who with the help of architect and planner Karl Langer laid out the first canal estates of Rio Vista and Miami Keys across the mid-1950s in today’s Broadbeach Waters. He inverted the so-called Radburn Plan – an American invention in which houses face each other across grass, turning their backs on the street – to create communities over water.

Plenty of decent and half-decent modernist buildings have been raised and razed over the last six or seven decades. But the urban-scale structures of the canal estates are the most enduring monuments to a vision for the Gold Coast. They capture the moment when rapid growth seemed inevitable, but had not yet begun.

In the 1960s, developer-mayor Bruce Small (“Think Big, Vote Small!”) set out to cement the image of the Gold Coast as one of uninhibited pleasure: a lifestyle city. His schemes, like Paradise City (another Langer project), were less the standalone townships he envisaged and more a blueprint for the first generation of the Gold Coast’s suburban sprawl. First extending west from the Nerang River, it now reaches as far as it can to both north and south.

More than a century earlier, British settlement of the area had also arrived from these opposite directions. Timber-fellers made their way north along the Pacific coast from Sydney and past Port Macquarie, putting the area into play with the regional and global trade in native Australian timbers. Soldiers and prisoners also travelled south from the penal settlement at Brisbane, sometimes with official blessing, but just as often not.

Violence could be met with violence as locals encountered these new visitors, just as trade and the exchange of goods and skills could be conducted peaceably. (Witness the traditional bark-roofed dwellings of those first “explorers”.) The arrival of the British Empire to Moreton Bay changed life there irredeemably – but set the tone for its history from the 1840s onwards.

One image of the Gold Coast’s agricultural history that sticks in my mind dates from 1865. It depicts Pacific Island workers in the fields of the Manchester Cotton Company in what remains today a low-density riverside suburb behind Surfers Paradise. The American Civil War had made a hole in the supply of raw materials for England’s textile industry, which enterprising farmers and local industrialists sought to plug by experimenting with new kinds of crops.

A drawing of Captain Towns’s ‘Townsvale’ cotton plantation, Veresdale, ca. 1865.

Artist unknown. Gold Coast City Libraries Local Studies Collection, Author provided

A drawing of Captain Towns’s ‘Townsvale’ cotton plantation, Veresdale, ca. 1865.

Artist unknown. Gold Coast City Libraries Local Studies Collection, Author provided

The experiment ultimately failed. But other crops took their place in a series of efforts to match the qualities of the land and climate with regional and international demand, even as timber continued to be extracted and waterways were tamed for transportation, the mitigation of flooding provoked by timber extraction, transformation of swamplands into farms, and forms of aquaculture.

These successive efforts gave rise to villages, each requiring basic infrastructure and communication, one with the next. Although the impression today is of the Gold Coast as a string of seaside towns melded together through infill growth, these agricultural towns are the basis for the city’s current extent and structure.

Transformed by tourism

Among the industries tried and tested on the Gold Coast, none matched the prominence or impact of tourism. Its importance has been both economic and cultural, decisively reorientating the city towards the beaches of today’s Broadwater, site of the Gold Coast Aquatic Centre, and, to the south, the Pacific beaches from Main Beach to Tugun.

The first house in coastal Southport was among the most remote outposts of a major sheep station, looking inland rather than towards the ocean. From the 1880s to the 1920s, though, Australia took to the beach with vigour. Southport’s early success as a township is a product of that national reorientation, just as the Gold Coast was later a product of the enthusiastic post-war embrace of the vacation.

A postcard of Southport Pier looking east from Star of the Sea Convent, ca. 1900.

Photographer unknown. Gold Coast City Libraries Local Studies Collection, Author provided

A postcard of Southport Pier looking east from Star of the Sea Convent, ca. 1900.

Photographer unknown. Gold Coast City Libraries Local Studies Collection, Author provided

The proliferation of motels, caravan parks and travellers’ lodges was already marked by the 1950s. By the 1960s these had started giving way to apartment towers of ten, 20, 40 floors in height.

It all happened quickly and with few controls. This gave the Gold Coast a reputation as a developers’ playground. It gave it, too, its distinctive shape.

The Pacific Highway, Surfers Paradise, in 1965, when the development boom was picking up pace.

Photographer: George Barnes/Gold Coast City Libraries Local Studies Collection, Author provided

The Pacific Highway, Surfers Paradise, in 1965, when the development boom was picking up pace.

Photographer: George Barnes/Gold Coast City Libraries Local Studies Collection, Author provided

Architect Bill Heather, in the late 1970s, likened the city to 19th-century Chicago: not in the scale of building, but in the rapidity of change. The cranes have, over the decades, come and gone, always, though, offering a visible sign of the Gold Coast’s economic health.

Over time, though, the trend has been to build higher and higher. Integrated resort towers fulfilled the desires of their investors and residents while altering one by one the city’s skyline. This, too, has played out at ground level, with the Gold Coast’s urban figure changing with each new subdivision, shopping centre and railway station.

The cameras trained on the Commonwealth Games expose this fascinating variety and depth, but this is easily overlooked if we see it as a simple dichotomy of a city core and its suburbs; Surfers Paradise and everywhere else.

This article is based on observations presented to the Commonwealth Club at the residence of the Australian Ambassador to Italy in Rome on April 12.

Authors: Andrew Leach, Wallace Fellow, Villa I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, and Professor of Architecture, University of Sydney

Read more http://theconversation.com/looking-past-the-gold-coast-the-world-sees-today-94504