In Open Cut exhibition, protest art challenges visitors to take action

- Written by Kirrily Jordan, Research Fellow, Australian National University

Can art translate to political action? An exhibition dealing with “development” in the Northern Territory, Open Cut, suggests there is power in storytelling through the visual arts. In a recent survey of those who’d seen the Sydney show, most people said they would take some further action on the issues raised by the artworks, sometimes in surprising ways.

Artists Jacky Green and Therese Ritchie and scholar Seán Kerins collaborated with Indigenous peoples of the southwest Gulf Country on Open Cut. They tell a story about the impact of settler-colonial “development” on Aboriginal land and people, asking who benefits and who bears the costs.

Jacky Green, The Christmas Father, 2017, 99 x 92cm, acrylic on canvas. Here the ‘Christmas Father’ from the mining company hands out ‘Toyota motorcars, just like lollies’ to Traditional Owners in exchange for signing agreements. Jacky Green

Green’s paintings show how he experiences the impacts of mining on Garawa, Gudanji and Yanyuwa country. He depicts the destruction of land, culture and sacred sites, and what he sees as flawed agreement processes where miners throw “lollies” (like cash or food) to Traditional Owners in return for their cooperation. A timeline situates Green’s work in a story dating back to colonial efforts to clear people off land to make way for the pastoral industry. It suggests those same colonial processes are ongoing, with government approvals for mining projects largely ignoring the needs of the region’s Indigenous peoples.

Read more: Friday essay: can art really make a difference?

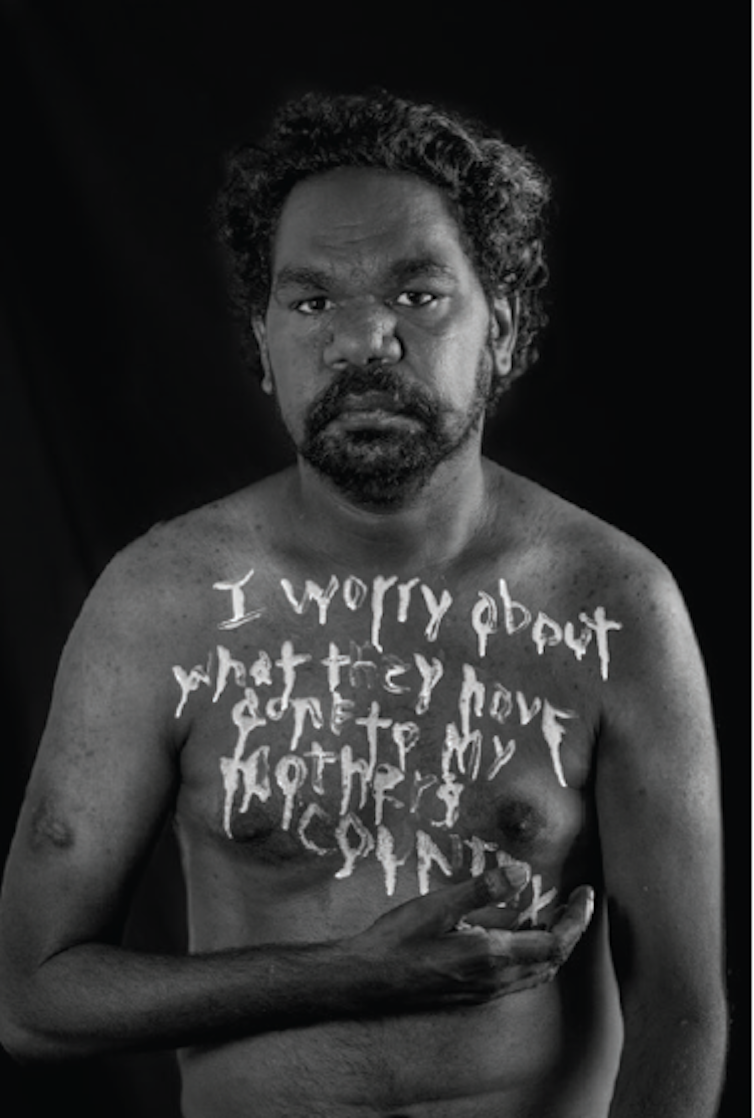

Not all traditional land owners are against mining. But Ritchie’s photographic portraits show how it is experienced by many Garawa, Gudanji and Yanyuwa people. In slogans painted across their arms and chests, English words like ‘“sulphur dioxide” and “inter-generational despair” mix with Garawa words such as Nancy McDinny’s Mikur Narri Kurayrritjerr Yarji Nurrungi (Stop mining. We don’t want no more).

Therese Ritchie, Ian Davey, 2017, digital print on Ilford Monofibre Silk, 84 x 56cm. ‘I worry about what they have done to my mother’s country.’ Therese Ritchie

Therese Ritchie, Ian Davey, 2017, digital print on Ilford Monofibre Silk, 84 x 56cm. ‘I worry about what they have done to my mother’s country.’ Therese Ritchie

Art has long played a role in political protest. But opinions remain divided on whether it has the power to bring about social change. Is it “preaching to the converted?” Does it have any effect beyond the gallery walls?

Of the 25 visitors we spoke to, 18 people said they were now better informed about the issue. Some had known nothing about it before. For most, though, the exhibition extended existing knowledge. Many people found the photographs particularly moving because they “put a human face to the issue”. The combination of photos and textual information seems to have been especially informative, with people who read the timeline more likely to say they had learnt something new.

Read more: Indigenous communities are losing out in the development of northern Australia

Can art provoke action? Nineteen people said they were likely to take action as a result of seeing Open Cut, not always in predictable ways. Most said they would talk about it with friends. A nursing student said it inspired her to do a placement with Aboriginal people. Two public servants said it would directly impact their work, paying more attention to related legislation, or asking policy-makers to see the exhibition. As one visitor told us:

The first thing is I’ll distribute the exhibition catalogue to the relevant ministers.

One person was ready to take direct action, saying he’d go to the remote community of Borroloola and stand with people protesting on the ground.

Jacky Green gives a floor talk in front of Seán Kerins & Therese Ritchie’s timeline, Developing the North, in Darwin 2017. Author provided

So what is the role for art in social change? Some theorists argue that to create social change we must reorient our culture as well as our institutions. Art can change culture by bringing attention to injustices and imagining an alternative future.

Therese Ritchie, Nancy McDinny, 2017, digital print on Ilford Monofibre Silk, 84 x 56cm. Therese Ritchie

Others point to a role for the arts because of human psychology. Scholar Stephen Duncombe argues that because people tend to reject facts that don’t fit their preexisting frames, “truth and power belong to those who tell the better story”. Art can create the stories that will get people on board.

According to philosopher Martha Nussbaum, art can position people we don’t know within our “circle of concern,” so that we are more likely to act in their interests.

There is enormous value to Open Cut beyond its instrumental purpose. But the artists clearly hope it will have a practical effect, helping Garawa, Gudanji and Yanyuwa peoples in their pursuit of justice. In the current climate, art that encourages critical reflection on “justice” and “development” may be more needed than ever.

I would like to thank Jacky Green, Therese Ritchie and Seán Kerins, as well as artists Nancy McDinny and Stewart Hoosan, for allowing me to survey visitors to the exhibition and for their insights into the works.

Open Cut is showing at Sydney’s The Cross Arts Projects until March 31. It will open at Brunswick’s Counihan Gallery, Brunswick on June 9.

Authors: Kirrily Jordan, Research Fellow, Australian National University