NAPLAN only tells part of the story of student achievement

- Written by Rachael Jacobs, Lecturer in Arts Education, Western Sydney University

Since it was introduced in the 1800s, standardised testing in Australian schools has attracted controversy and divided opinion. In this series, we examine its pros and cons, including appropriate uses for standardised tests and which students are disadvantaged by them.

The National Assessment Program – Literacy And Numeracy (NAPLAN) had its 10th birthday this year, but few well-wishers came to the party.

Administered in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9, NAPLAN measures the performance of educational programs, schools and each student’s literacy and numeracy achievements against benchmarks. In short, the aim of NAPLAN is to ensure that students’ and the nation’s literacy and numeracy skills are improving. This year, 10 years of data revealed that little has changed since NAPLAN began.

After millions of dollars of investment, as well as the abundance of data that NAPLAN has created, we are still not seeing amazing leaps and bounds in achievement. The nation is effectively standing still.

NAPLAN is good at measuring differences and change over time

NAPLAN gives us a picture of several aspects of students’ learning. These include: their performance under test conditions, their basic use of punctuation, grammar, spelling, numeracy skills and writing an exposition or narrative text.

NAPLAN has provided data to help us quantify the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students’ literacy and numeracy, and provide indicators of where the gap is closing.

We can see the differences in boys’ and girls’ achievements, and the significant difference that a parent’s level of education makes to results.

NAPLAN can, importantly, track a student’s improvement, or lack thereof, from one exam to the next. It can also highlight changes, although it can’t specify the factors involved in it.

Finally, NAPLAN can identify areas of disadvantage or need, for example geographical areas, state or territory differences or demographics.

NAPLAN cannot measure creativity or engagement

Despite all that NAPLAN can measure, it only tells part of the story of literacy and numeracy achievement. Results may not show growth of learning in schools with students from low socio-economic backgrounds or culturally and linguistically diverse students, because it only measures a narrow skill set on one particular day of the year. It does not represent student achievements across the year, nor across the breadth of the curriculum which schools use to evaluate their programs.

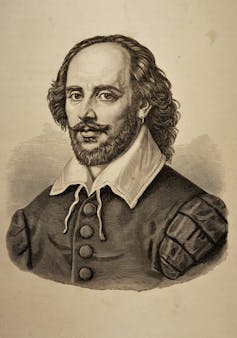

The Bard of Avon’s creative use of language and love of making up words would likely earn him a poor score on a NAPLAN test.

Shutterstock

The Bard of Avon’s creative use of language and love of making up words would likely earn him a poor score on a NAPLAN test.

Shutterstock

It also does not measure engagement in learning. Engagement can look like students’ enjoying reading, willingness to engage in numeracy tasks or whether they are using these skills outside a test situation.

This leaves little room for creative play with the style of writing prescribed, promoting very structured teaching of the texts. It’s far easier to provide students with a simplistic structure and key language features, rather than encourage a creative response with more complexity. An assessor may not value the difference in writing style, as it is not reflected in the marking criteria. One wonders how Shakespeare would have performed on NAPLAN. Our prediction is that his phrase “the world’s my oyster”, would have placed him in the bottom two bands.

NAPLAN’s influence on learning

This narrow version of literacy, numeracy and writing isn’t reflected in the rich learning that occurs in classrooms. NAPLAN places children as young as eight in an exam environment, and asks them to think in a way they aren’t used to. Classroom life in year 3 is usually more accustomed to collaborative learning, using problem-solving and discovery methods are essential for knowledge and understanding.

In contrast, NAPLAN reflects little of the ways that children understand and interpret the world. Two weeks before NAPLAN, many years 3 and 5 teachers start teaching to the test by developing exam skills, practising answering multiple choice questions, teaching the structure and language features of an exposition and/or narrative text. Teachers feel they must simulate the exam environment, practice and even guess the questions that might be asked.

This narrows the curriculum as well as the types of literacy and numeracy activities that students usually engage in as part of their learning. It takes up classroom time that could be spent teaching literacy and numeracy skills meaningfully, by reading quality children’s literature, creating various text types, engaging in process drama pedagogies or trying creative tasks.

Standardised tests like NAPLAN also diminish the joy of learning. Teachers have reported that 90% of students feel stressed before the test. In fact, a 2016 study found that students in high school do not see the relevance of NAPLAN to their education. Year 7 students even felt it stopped their learning.

Dangerously, NAPLAN frames mistakes as bad. Mistakes are essential if schools are going to encourage original thoughts. Lateral and creative thinking is required to conquer challenges like climate change, global inequality and rising global conflicts. Students will need to take risks, understand that problems may have multiple solutions and they mustn’t only look for a singular right answer.

Creative alternatives

Teachers are not to blame for any of these issues. Throughout the teaching year, teachers use creative strategies to improve students’ outcomes. Philosophy has been found to make a significant and impressive difference. Sydney Theatre Company’s School Drama program has been found to improve literacy outcomes as well as empathy, confidence, motivation and engagement. These approaches are not available to every child in every school. This should be a priority, but education is like a large ship - slow to turn around. Wide-scale reform that prioritises creativity and philosophical thinking takes time.

NAPLAN, on the other hand, is high-stakes testing. Schools are required to administer it with additional funding tied to results of underachieving students and that may not accurately represent data for the whole school population if all students do not complete the tests. Using a centrally created test puts enormous pressure on every student, teacher and principal to perform. It discards teachers’ contextual knowledge about the students and the learning environment. Results are published as a comparative analysis of schools on the My School website.

Despite 10 years of minimal breakthroughs and a plethora of evidence that shows that NAPLAN may do more harm than good, there is no sign it’s going anywhere except online.

Governments love NAPLAN. It contains all of their favourite buzz-words: transparency, accountability, data and quality. In the process, look at what it denies our students: innovation, creativity, risk, originality and joy. These are far less attractive to politicians, more difficult to measure in a national multiple choice test, but far more relevant to children’s future achievements.

Authors: Rachael Jacobs, Lecturer in Arts Education, Western Sydney University

Read more http://theconversation.com/naplan-only-tells-part-of-the-story-of-student-achievement-86144