Diaries, petticoats and copious research: a rare glimpse into Mirka Mora's artistic process

- Written by Sabine Cotte, PhD candidate, Conservation of Cultural Materials, University of Melbourne

In February 1983, Melbourne artist Mirka Mora spent two weeks in Perth, painting an almost 21-metre long frieze of six zinc panels. Drawing on imagery as diverse as shipwrecks, cherubs, local flora, black swans and harp-playing quokkas, the mural was made in public during the city’s festival. People flocked to the forecourt of the Perth Concert Hall to watch Mora in action.

At the time, she was already famous: her painted tram had run the streets of Melbourne for five years; she had just painted the foyer of Melbourne’s Playbox Theatre and was teaching her techniques of soft sculpture, embroidery and painting on textile. Her flamboyant personality was well known, ever since her bohemian days of working and partying with her artist friends in the restaurants she ran with her husband Georges.

One of the six paintings in the Mirka Mora Perth Festival Mural 1983; synthetic polymer paint on tin, 6 panels, each 120 x 280 cm (approx.) Detail.

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Paul Swain, 2015.

One of the six paintings in the Mirka Mora Perth Festival Mural 1983; synthetic polymer paint on tin, 6 panels, each 120 x 280 cm (approx.) Detail.

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Paul Swain, 2015.

Less known is Mora’s incredible professionalism, her scholarly way of researching her major works and her meticulous preparation for them. Her diaries from this time offer an insight into this important artist’s work. Mora had no formal training in fine arts, having left school at the age of 13 during the second world war, when her family was arrested and subsequently gone into hiding in the French countryside.

She compensated for this by extensive reading in art history, philosophy and literature, and studying arts treatises and artists’ writings. As she likes to say, “books are the best teachers”, and they are the main source of inspiration for her own imagery. Her intellectual curiosity is wide: she has sought inspiration from medieval bestiaries, the symbolism of colours in the African outdoors, Greek mythology and Christian iconography. For the Perth mural, she studied the local history and scenery, observing the West Australian landscape, its colours and plants, and noting the main features of the region.

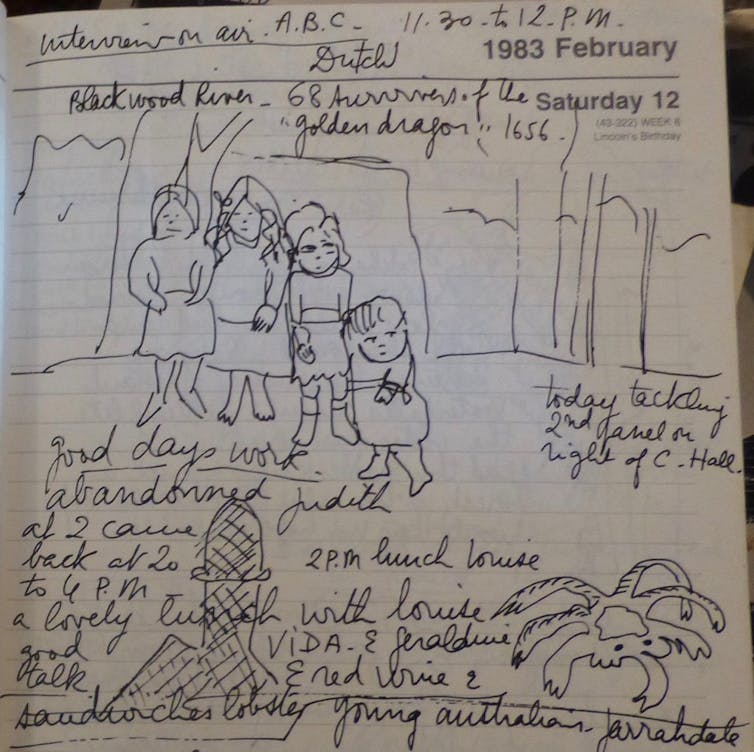

A page of Mirka Mora’s diary with sketches of prospective images for the final painting.

Sabine Cotte

The story of the creation of this painting is a fascinating one. Its subsequent fate is also intriguing. When I came across it while researching Mora’s techniques for my PhD, it was at first impossible to find; she recalled only that a lady involved in contemporary art had bought the panels after the festival.

A page of Mirka Mora’s diary with sketches of prospective images for the final painting.

Sabine Cotte

The story of the creation of this painting is a fascinating one. Its subsequent fate is also intriguing. When I came across it while researching Mora’s techniques for my PhD, it was at first impossible to find; she recalled only that a lady involved in contemporary art had bought the panels after the festival.

It took some perseverance to finally locate them. The lady was Veda Swain, director of Greenhill galleries in Adelaide and Perth; she’d had the paintings shipped to her home in Adelaide, where they were stored and kept in perfect condition for the next 30 years. Thanks to her son Paul Swain’s generosity, they have now been donated to Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne.

Mirka Mora at work on the Perth painting.

Author provided

Mirka Mora at work on the Perth painting.

Author provided

Mora painted this work in ten days, with the help of a local artist, Judith van Heeren. She used enamel - a thin and runny paint - which is difficult to apply to vertical metal walls. Still, she easily mastered it due to her previous experience; she had used enamel on board in the late 50s (including a self portrait famously done with a pot of paint left by Sydney Nolan at Heide) and when painting the tram.

Sailing is a big part of WA life, so Mora mixed past and present sailing events in her painting. The infamous wreck of the Pericles near Cape Leeuwin interested her, as she liked the image of the 100 ladies on board - who all survived - floating and being rescued from the water. But the panels also feature the Perie Banou yacht on which WA sailor Jon Sanders circumnavigated Antarctica solo for the first time in 1981, and the Reliance yacht, defender in the 1903 America’s Cup. All these gracefully float between winged cherubs, luxuriant vegetation, a portrait of Sister Ursula Frayne, founder of the first private school in WA in 1849, and the rings of a giant, double-headed snake.

Detail of the Pericles and the floating ladies, Mirka Mora Perth Festival Mural 1983; synthetic polymer paint on tin, 6 panels, each 120 x 280 cm (approx.)

Heide Museum of Modern Art, gift of Paul Swain, 2015.

Detail of the Pericles and the floating ladies, Mirka Mora Perth Festival Mural 1983; synthetic polymer paint on tin, 6 panels, each 120 x 280 cm (approx.)

Heide Museum of Modern Art, gift of Paul Swain, 2015.

She organised the composition in a long sequence, framed by a decorative frieze, inspired by the medieval Bayeux tapestry. Historic events and characters are blended with local landmarks such as the Perth Concert Hall, beautiful West Australian black swans, a bottle of olive oil from Cooladerra farm, quokkas and Aboriginal wandjinas, requested by the writer Lady Mary Durack, who came to visit several times

Detail of one panel, with Sister Ursula Frayne, fantastic creatures and vegetation. Mirka Mora Perth Festival Mural 1983; synthetic polymer paint on tin, 6 panels, each 120 x 280 cm (approx.)

Heide Museum of Modern Art, gift of Paul Swain, 2015.

Detail of one panel, with Sister Ursula Frayne, fantastic creatures and vegetation. Mirka Mora Perth Festival Mural 1983; synthetic polymer paint on tin, 6 panels, each 120 x 280 cm (approx.)

Heide Museum of Modern Art, gift of Paul Swain, 2015.

In her diary, historic references, book extracts, personal observations and technical notes are interspersed with small sketches that show her visual and literary mind at work.

“Beautiful scarlet, white and yellow-flowered eucalypti overhang red gravel roads. Characteristic of Perth - black oak, stunted gums give the dark native bush a generally somber appearance,” she wrote on Feburary 10.

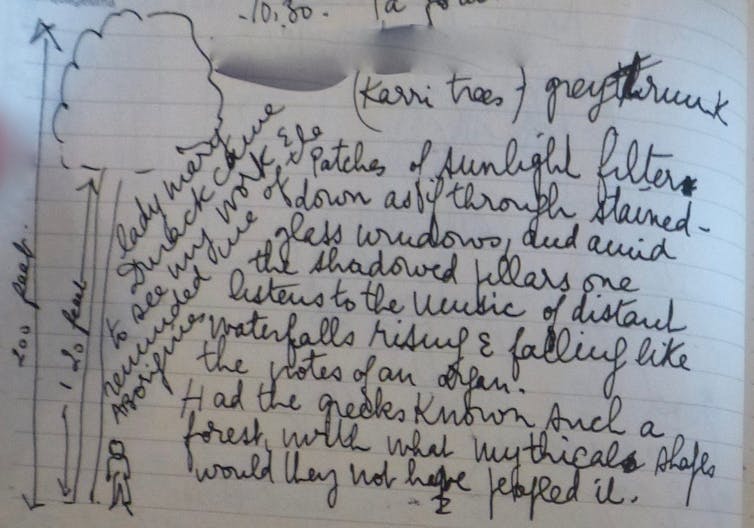

“Sound of aeolian song of the wind in the branches of the karri … its voice is heard in spiritual, mysterious echoes like the music of muffled bells far up in an old cathedral tower,” she wrote two days later.

A page of Mirka Mora’s diary with a sketch of a karri tree and comments on the landscape.

Sabine Cotte

Working in public added an extra dimension to Mora’s work. On the plane to Perth, she made friends with two men, exchanging drawings for whiskies. While there, she drew attention with her original sense of dress, including Victorian petticoats and culottes and a big straw hat. One day, she left her shoes behind at a restaurant and continued painting barefoot. Another, she painted a mermaid on the street from a paint pot knocked over by the wind. It threw the city council into a terrible dilemma over its cleaning.

A page of Mirka Mora’s diary with a sketch of a karri tree and comments on the landscape.

Sabine Cotte

Working in public added an extra dimension to Mora’s work. On the plane to Perth, she made friends with two men, exchanging drawings for whiskies. While there, she drew attention with her original sense of dress, including Victorian petticoats and culottes and a big straw hat. One day, she left her shoes behind at a restaurant and continued painting barefoot. Another, she painted a mermaid on the street from a paint pot knocked over by the wind. It threw the city council into a terrible dilemma over its cleaning.

She was so driven by her work that one day she left her hotel across the road wearing only a pair of Victorian underwear (drawers that reached below the knee, with separate legs joined only at the waist). She had painted for an hour before realising that she had graced passers-by with the occasional glimpse of her bare bottom, and had to rush back to put a skirt on.

Mirka Mora with one of her painted soft sculptures, March 2014.

Sabine Cotte

Mirka Mora with one of her painted soft sculptures, March 2014.

Sabine Cotte

People gave her funny presents such as an antique porcelain Punch (no Judy), a pair of buttoned up shoes and a bottle of wine (carried by a big dog). Mora says that she “liked to share and to think that while people are watching they are also learning something”.

It is easy to forget that being a successful woman artist was the exception at this time. Mora’s approach to the public, her accessibility and her clever use of material culture have helped build her reputation and personal myth, but they also define a place for her within feminist art movements of the 1980s.

Authors: Sabine Cotte, PhD candidate, Conservation of Cultural Materials, University of Melbourne