We just Black matter: Australia's indifference to Aboriginal lives and land

- Written by Chelsea Bond, Senior Lecturer, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit (ATSIS Unit), The University of Queensland

This article is the second in the Black Lives Matter Everywhere series, a collaboration between The Conversation, the Sydney Democracy Network and the Sydney Peace Foundation. To mark the awarding of the 2017 Sydney Peace Prize to the Black Lives Matter Global Network, the authors reflect on the roots of and responses to a movement that has re-ignited a global conversation about racism. The 2017 Sydney Peace Prize will be presented on November 2 (tickets here).

We say “Black Lives Matter” but shit, the fact that matter is, we just Black matter to them, this shit keep happening.

In a uniquely Aboriginal articulation of the global Black Lives Matter movement, Batdjala rapper Birdz sings not of Rice, Garner, Martin or Bland. Instead he sings of Mulrunji, Elijah, Yock, Hickey and the Bowraville children – each of whom died in seemingly different circumstances.

What ties them together, however, is the indifference to their deaths and the apparent disposability of Black lives in Australia.

Birdz performs his song Black Lives Matter for NAIDOC Week live on triple j.Much of the media attention in Australia surrounding the US-led Black Lives Matter movement has focused on police brutality and the murder of young African-American men on public streets, captured on smartphones and dashboard cameras.

Meanwhile, the murders of Aboriginal people in Australia have been less visible. If mentioned at all, Aboriginal deaths at the hands of the state are variously framed as “suspicious”, “unknown”, “accidental” or “inevitable”, despite the presence of CCTV footage, protests, perpetrators, witnesses, coronial inquiries and a royal commission.

Further reading: Deaths in custody: 25 years after the royal commission, we’ve gone backwards

Where murder is not even considered manslaughter, where Black witnesses are deemed “unreliable”, where royal commission recommendations aren’t implemented, where coroners refuse to exercise their power to make recommendations, and where White murderers of Black children enjoy the privilege of being unnamed for their own protection, it is blatantly clear whose lives really matter in Australia.

And there really is nothing mysterious about the deaths of Aboriginal people in Australia, either.

The settlers have long insisted that our death was destined, that our race was doomed, and that we, as a people, were vanishing. Our disappearance was inevitable because it was necessary to sustain terra nullius, the foundational myth of Australia. Black deaths rationalised White invasion and land expansion in Australia.

A print ad for GenerationOne that was released in March 2010.

GenerationOne/Coloribus

A print ad for GenerationOne that was released in March 2010.

GenerationOne/Coloribus

In a little over 100 years of White presence, they did not feel it was necessary to include us in their Constitution. Having been so successful in their work, they were anticipating our imminent departure – not to another land, but rather to be buried in our own lands.

In our dying, rather than in our living, our bodies mattered most to the colonial project.

Black lives matter: in death and deviance

White indifference to Black suffering has a long tradition in Australia. It remains ever-present, even in the supposedly benevolent contemporary policy agendas of “Indigenous Advancement” and “Closing the Gap”.

We are told by the Australian government:

The Australian government made Indigenous affairs a significant national priority and has set three clear priorities to make sure efforts are effectively targeted – getting children to school, adults into work and building safer communities.

Clearly, what is actually targeted here are Black lives and the unsafe Black body – which, we are told, are incapable of working or attending school. We see the gaze transfixed not on the systems that create disadvantage, but on remedying the behaviours of Black people through compliance to systems that have always failed us – and, let’s be honest, have deliberately excluded us.

Focusing on Black lives in this instance both lays blame on, and makes claims of, Black deviance from White norms, values, standards and expectations. The deviation from Black lives to White lives sanctions a “new” targeting of Black lives by the state, and necessitates the continuation of White control over us and our lands.

Black deviance (statistical or otherwise) has been a useful narrative device for the settlers.

Black deviance supports claims of White benevolence, in which White people are simultaneously positioned as our aspirational goal and saviours. It suggests to us that Black lives matter to them. Yet in emphasising our deviance, the sins of a system that White people uphold and benefit from remains unnamed and unnoticed.

Only last month we witnessed the routine deployment of Black deviance to sustain White virtue in the Queensland Department of Education and Training’s own marketing.

The Black lives we see are not her students, but they need not be. Black lives only matter when they prop up claims of White intellectual and moral superiority, and it is in a state of deviance that our bodies, that our troublesome children and their neglectful parents, are suddenly hyper-visible.

But Black deviance doesn’t just make settlers look good: it rationalises them taking greater control over the lives and lands of Aboriginal people. Let’s not forget that it was via mythologies of Black deviance that the Northern Territory Emergency Response (otherwise known as the Intervention) was introduced and the Racial Discrimination Act suspended.

Despite the Intervention’s inherently racist nature, it was framed as a benevolent act to Black women and children. Through the narratives of Black deviance and allegedly neglectful #IndigenousDads, attention was shifted away from the actual abuse of Aboriginal children within the youth justice system in the Northern Territory.

Further reading: Ten years on, it’s time we learned the lessons from the failed Northern Territory Intervention

Black deviance has worked well for the Australian health system too, in rationalising the enduring and appalling health inequalities that Indigenous peoples suffer. Much like the education system, the health system asserts a public moral stance of benevolence to avoid scrutiny over its ongoing refusal to care properly for Aboriginal people.

The coronial inquiry into the tragic death of Ms Dhu in police custody ruled that it was also medical staff who “disregarded her welfare and right to treatment during her three visits to hospital in as many days”.

The failure of the health system to provide care to Aboriginal people is nothing new. And access to basic health care has been a long and hard-fought battle led by Indigenous activists across Australia over many decades. It was not until 1989, after two centuries of invasion, that the first National Aboriginal Health Strategy was devised.

Since 2013, the current National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan has had, as its vision, a health system free of racism for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. But a cursory glance at coronial inquiries into Aboriginal deaths in hospitals in recent years reveals any number of preventable deaths that came about through an indifference to Black lives and Black suffering.

From the excessive use of restraints to the refusal to provide appropriate health care, the names of the deceased remain unknown to most Australians – as do the crimes of the healthcare professionals responsible, thanks to the health and justice systems that protect them.

Even in death, descriptions of Aboriginal victims at the hands of the state frequently focus on Black deviance as a mitigating factor.

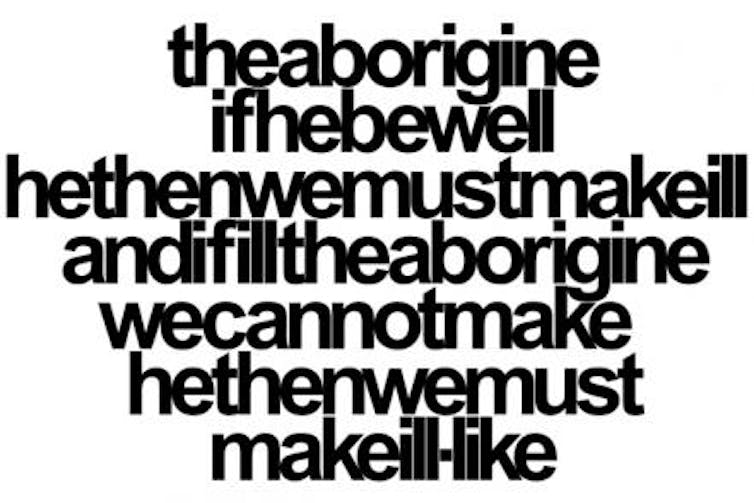

Vernon Ah Kee/Milani Gallery

Black deviance operates as an alibi for racism and White supremacy. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, where Black deviance was successfully deployed to deflect attention away from the role of police brutality.

The inquiry found that not one of the 99 Aboriginal deaths investigated was a result of “unlawful, deliberate killing of Aboriginal prisoners by police and prison officers”.

Instead, we were told that 37 of these deaths were attributable to disease, while 30 were self-inflicted hangings and 23 were caused by “other forms of trauma, especially head injuries”. Another nine were associated with dangerous alcohol and drug use.

Consequently, much of the attention around Black deaths in custody has focused on the apparently inevitable deaths of sick Aborigines rather than the violence of the state. But when police officers threaten Aboriginal men with tying a noose around their neck and publicly mock Aboriginal people who have died in custody as a result of alleged “self-inflicted hangings”, it is little wonder that Aboriginal people are sceptical.

Black lands matter

White benevolence really does feel brutal for Blackfullas in this country. So, it is hardly surprising that the Black Lives Matter movement, with its emphasis on countering racism and White supremacy, has a certain appeal for Blackfullas.

Co-founder Alicia Garza explains that the movement seeks to tackle the “deep-seated disease” of racism through a deeper conversation around citizenship:

We really need to be talking about this question of citizenship, which I think is huge. I feel like what Black folks are fighting for in this moment is what we’ve been fighting for the whole time - which isn’t citizenship, like papers, but it’s citizenship like dignity. Like humanity. Right? And access.

Alicia Garza, Patrisse Khan-Cullors and Opal Tometi, the women who created the hashtag that galvanised a movement , discuss Black Lives Matter.Despite the promise of Black Lives Matter, it has not been taken up as a central political movement by Blackfullas in Australia. Perhaps it is because, as a people who are both Black and First Nations, we cannot embrace an emancipatory agenda that is silent about the significance of the relationship between Black lands and Black lives.

Blackfullas are not seeking a revitalised citizenship that recognises our dignity and humanity – we are insisting upon our sovereignty as First Nations peoples.

We refuse to talk about our lives independently of our land. We remind them every day that we are still here in this place – and it is their presence on our lands that poses the real problem, not our lives.

We refuse to appeal to the benevolence of the colonisers for our lives to matter, because we know that their existence on this continent remains legally predicated upon our non-existence.

That’s why I’m with Birdz on this one:

Shit. The fact that matter is, we just Black matter to them.

You can read the first article in the series here.

Vernon Ah Kee/Milani Gallery

Black deviance operates as an alibi for racism and White supremacy. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, where Black deviance was successfully deployed to deflect attention away from the role of police brutality.

The inquiry found that not one of the 99 Aboriginal deaths investigated was a result of “unlawful, deliberate killing of Aboriginal prisoners by police and prison officers”.

Instead, we were told that 37 of these deaths were attributable to disease, while 30 were self-inflicted hangings and 23 were caused by “other forms of trauma, especially head injuries”. Another nine were associated with dangerous alcohol and drug use.

Consequently, much of the attention around Black deaths in custody has focused on the apparently inevitable deaths of sick Aborigines rather than the violence of the state. But when police officers threaten Aboriginal men with tying a noose around their neck and publicly mock Aboriginal people who have died in custody as a result of alleged “self-inflicted hangings”, it is little wonder that Aboriginal people are sceptical.

Black lands matter

White benevolence really does feel brutal for Blackfullas in this country. So, it is hardly surprising that the Black Lives Matter movement, with its emphasis on countering racism and White supremacy, has a certain appeal for Blackfullas.

Co-founder Alicia Garza explains that the movement seeks to tackle the “deep-seated disease” of racism through a deeper conversation around citizenship:

We really need to be talking about this question of citizenship, which I think is huge. I feel like what Black folks are fighting for in this moment is what we’ve been fighting for the whole time - which isn’t citizenship, like papers, but it’s citizenship like dignity. Like humanity. Right? And access.

Alicia Garza, Patrisse Khan-Cullors and Opal Tometi, the women who created the hashtag that galvanised a movement , discuss Black Lives Matter.Despite the promise of Black Lives Matter, it has not been taken up as a central political movement by Blackfullas in Australia. Perhaps it is because, as a people who are both Black and First Nations, we cannot embrace an emancipatory agenda that is silent about the significance of the relationship between Black lands and Black lives.

Blackfullas are not seeking a revitalised citizenship that recognises our dignity and humanity – we are insisting upon our sovereignty as First Nations peoples.

We refuse to talk about our lives independently of our land. We remind them every day that we are still here in this place – and it is their presence on our lands that poses the real problem, not our lives.

We refuse to appeal to the benevolence of the colonisers for our lives to matter, because we know that their existence on this continent remains legally predicated upon our non-existence.

That’s why I’m with Birdz on this one:

Shit. The fact that matter is, we just Black matter to them.

You can read the first article in the series here.

Authors: Chelsea Bond, Senior Lecturer, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit (ATSIS Unit), The University of Queensland