Research Check: can ‘Lightning Process’ coaching program help youths with chronic fatigue?

- Written by John Malouff, Associate Professor, School of Behavioural, Cognitive and Social Sciences, University of New England

Chronic fatigue syndrome involves experiencing a disabling level of fatigue for at least three months, where medical tests fail to show a biological cause. Adults, adolescents, and children can experience chronic fatigue syndrome. About 1% of youths develop the syndrome, which greatly affects their mood and decreases school attendance.

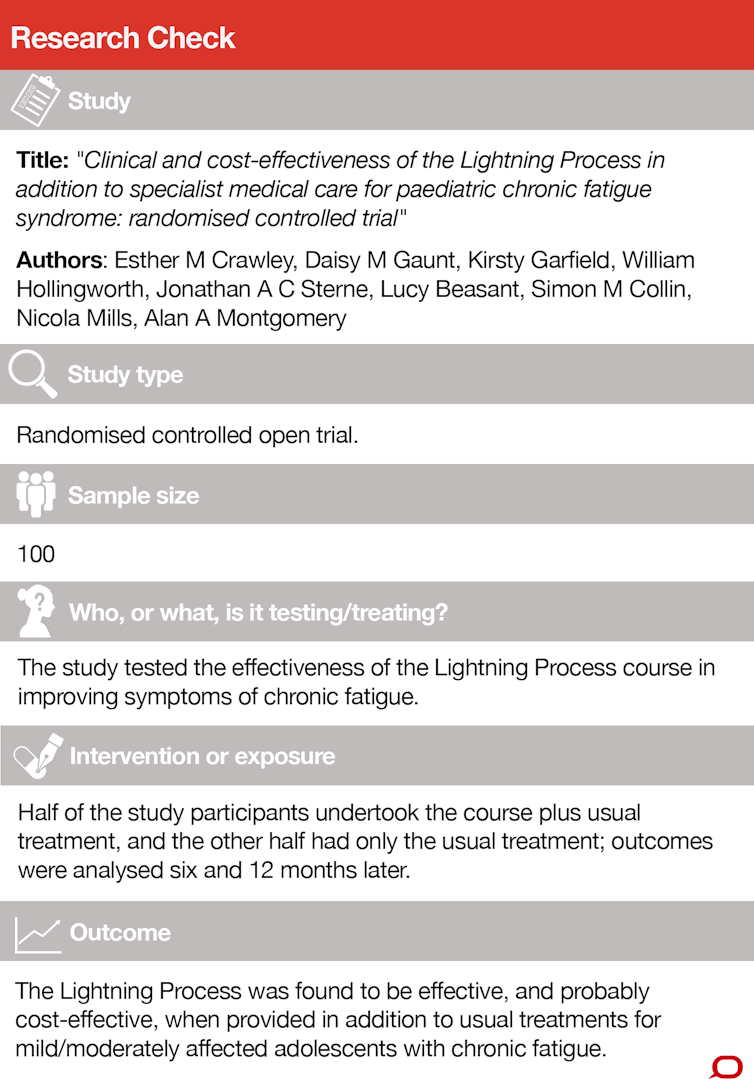

A research article published recently in the journal Archives of Disease in Childhood reported the effects of an intervention called the “Lightning Process”. The study found the Lightning Process added significantly to the effects of the usual treatment in the UK for chronic fatigue syndrome in youths.

The results immediately attracted media attention. But while the study did show a positive outcome, there are a few limitations that may have affected these results and should be mentioned.

Read more - Explainer: what is chronic fatigue syndrome?

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

What is the Lightning Process?

The Lightning Process is a psychological intervention developed by British osteopath Phil Parker. The 12-hour intervention, provided over three days, was developed for chronic fatigue syndrome, as well as other disorders.

The intervention, which can cost up to a few thousand dollars, involves three components that were outlined in the study:

Instruction on the stress response, on how the mind and body interact, and on how thoughts can have positive or negative effects;

Group discussion about these topics and about what trainees can change;

Individual identification of a relevant goal each participant wants to achieve, and the thinking that might help the person achieve the goal, such as walking more.

The Lightning Process has generated controversy because of claims of its effectiveness in the absence of solid evidence. It has also attracted criticism because it is a psychological intervention for a medical problem, which some sufferers perceive as undermining the severity of their symptoms.

What exactly did the study find?

The study was the first randomised controlled trial (meaning half the people in the study were allocated to receive the intervention, and half were not) of Lightning Process for chronic fatigue syndrome in youths aged 12 to 18. It compared the usual treatment in the UK, which involves gradually increasing activity level, to the usual treatment plus 12 hours of Lightning Process.

The results showed better outcomes for the group receiving Lightning Process. These better outcomes involved fatigue, physical functioning, anxiety, and school attendance over periods of six to 12 months. Participants in the usual treatment group also improved significantly over time, but not as much as those who received the Lightning Process.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

What is the Lightning Process?

The Lightning Process is a psychological intervention developed by British osteopath Phil Parker. The 12-hour intervention, provided over three days, was developed for chronic fatigue syndrome, as well as other disorders.

The intervention, which can cost up to a few thousand dollars, involves three components that were outlined in the study:

Instruction on the stress response, on how the mind and body interact, and on how thoughts can have positive or negative effects;

Group discussion about these topics and about what trainees can change;

Individual identification of a relevant goal each participant wants to achieve, and the thinking that might help the person achieve the goal, such as walking more.

The Lightning Process has generated controversy because of claims of its effectiveness in the absence of solid evidence. It has also attracted criticism because it is a psychological intervention for a medical problem, which some sufferers perceive as undermining the severity of their symptoms.

What exactly did the study find?

The study was the first randomised controlled trial (meaning half the people in the study were allocated to receive the intervention, and half were not) of Lightning Process for chronic fatigue syndrome in youths aged 12 to 18. It compared the usual treatment in the UK, which involves gradually increasing activity level, to the usual treatment plus 12 hours of Lightning Process.

The results showed better outcomes for the group receiving Lightning Process. These better outcomes involved fatigue, physical functioning, anxiety, and school attendance over periods of six to 12 months. Participants in the usual treatment group also improved significantly over time, but not as much as those who received the Lightning Process.

Half of the youths in the trial received usual treatment, half had the usual treatment plus the Lightning Process.

from www.shutterstock.com

How well done was the study?

The study procedures were published prior to the start of the study, making it hard to change methods to produce a desired finding. Participants were assessed using mostly well-validated measures before the intervention and for many months after.

The study had three notable weaknesses in its methods. These weaknesses limit how much can be made of the findings.

First, both the therapists and the clients knew which treatment they received. Hence, the zeal of the therapists or the desire of participants to please the researchers could have helped produce results in favour of the Process. Placebo effects may also have occurred: when participants think they’re getting a new, experimental treatment, placebo effects can lead to real or imagined improvements.

Second, the school attendance reports came from the young people themselves. It would have been more valuable to gather this information from official records.

Third, the Process participants received 12 extra hours of treatment. Hence, it’s not clear whether they improved more due to the content of that extra treatment or due to receiving more treatment.

What questions might be answered in the future?

The study showed a general problem in treating chronic fatigue: most of the potential participants with chronic fatigue syndrome who were contacted about entering the study chose not to enter. Also, some who entered the study failed to complete the intervention. No treatment works for someone who does not receive it. Attracting more young people with chronic fatigue to treatment remains a challenge.

The study did not compare Lightning Process with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for chronic fatigue. Of all treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome, CBT has the most evidence of producing positive effects. A meta-analysis of many studies showed that CBT tends to lead to moderate benefits. The Process intervention has instructional, cognitive, and behavioural components that are commonly included in CBT. So the Lightning Process could produce similar outcomes, given that many of these components overlap.

What comes next?

The study findings are important enough to suggest that more research on the Lightning Process is warranted. But the findings are from a single study, with a single set of researchers. As such, they do not justify a conclusion that someone with the disorder ought to seek this specific treatment.

Half of the youths in the trial received usual treatment, half had the usual treatment plus the Lightning Process.

from www.shutterstock.com

How well done was the study?

The study procedures were published prior to the start of the study, making it hard to change methods to produce a desired finding. Participants were assessed using mostly well-validated measures before the intervention and for many months after.

The study had three notable weaknesses in its methods. These weaknesses limit how much can be made of the findings.

First, both the therapists and the clients knew which treatment they received. Hence, the zeal of the therapists or the desire of participants to please the researchers could have helped produce results in favour of the Process. Placebo effects may also have occurred: when participants think they’re getting a new, experimental treatment, placebo effects can lead to real or imagined improvements.

Second, the school attendance reports came from the young people themselves. It would have been more valuable to gather this information from official records.

Third, the Process participants received 12 extra hours of treatment. Hence, it’s not clear whether they improved more due to the content of that extra treatment or due to receiving more treatment.

What questions might be answered in the future?

The study showed a general problem in treating chronic fatigue: most of the potential participants with chronic fatigue syndrome who were contacted about entering the study chose not to enter. Also, some who entered the study failed to complete the intervention. No treatment works for someone who does not receive it. Attracting more young people with chronic fatigue to treatment remains a challenge.

The study did not compare Lightning Process with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for chronic fatigue. Of all treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome, CBT has the most evidence of producing positive effects. A meta-analysis of many studies showed that CBT tends to lead to moderate benefits. The Process intervention has instructional, cognitive, and behavioural components that are commonly included in CBT. So the Lightning Process could produce similar outcomes, given that many of these components overlap.

What comes next?

The study findings are important enough to suggest that more research on the Lightning Process is warranted. But the findings are from a single study, with a single set of researchers. As such, they do not justify a conclusion that someone with the disorder ought to seek this specific treatment.

We shouldn’t change treatment off the back of one study. Especially one with limitations.

from www.shutterstock.com

If other studies with different researchers find something similar, then we might consider the intervention empirically supported for use in paediatric chronic fatigue syndrome.

A trial comparing Lightning Process to CBT would be valuable. Parents of young people suffering from chronic fatigue would like solid evidence about which treatment is most likely to help. - John Malouff

Peer review

I agree with the Research Check that this study has limitations, but I would perhaps be stronger in my criticisms of the study, as I think there are a few that haven’t been mentioned.

The treatment options the participants received were not standardised, and so because of the variety of treatment options available it’s difficult to evaluate what treatment worked best. All individuals also received a different number of sessions, which would have also impacted on the results from the study.

One point I would also raise is that the criteria used for diagnosing those in the study with chronic fatigue were very broad and did not take into account other criteria that are recognised in diagnosing chronic fatigue.

For these reasons, I think more research is needed before we can say this treatment has a benefit. Participants in the study should follow a standardised treatment and should not know which group they belong to in order to avoid a placebo effect. I would also make the suggestion researchers consider using a better method for establishing these individuals do suffer with chronic fatigue. - Lynette Hodges

Statement from the study author, Esther Crawley

I did a press briefing because it was important to me that the limitations and implications of this study were clear. For example, it was important to me that children with CFS/ME [chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis] and their parents understood that we have only tested LP [Lightning Process] in addition to specialist medical care. And that we could not say anything about adults with CFS/ME. I wanted it to be clear that many eligible children did not take part and some said this was because they didn’t want LP. I think most of these points were picked up by the press and on the whole, I was pleased with the reporting.

We shouldn’t change treatment off the back of one study. Especially one with limitations.

from www.shutterstock.com

If other studies with different researchers find something similar, then we might consider the intervention empirically supported for use in paediatric chronic fatigue syndrome.

A trial comparing Lightning Process to CBT would be valuable. Parents of young people suffering from chronic fatigue would like solid evidence about which treatment is most likely to help. - John Malouff

Peer review

I agree with the Research Check that this study has limitations, but I would perhaps be stronger in my criticisms of the study, as I think there are a few that haven’t been mentioned.

The treatment options the participants received were not standardised, and so because of the variety of treatment options available it’s difficult to evaluate what treatment worked best. All individuals also received a different number of sessions, which would have also impacted on the results from the study.

One point I would also raise is that the criteria used for diagnosing those in the study with chronic fatigue were very broad and did not take into account other criteria that are recognised in diagnosing chronic fatigue.

For these reasons, I think more research is needed before we can say this treatment has a benefit. Participants in the study should follow a standardised treatment and should not know which group they belong to in order to avoid a placebo effect. I would also make the suggestion researchers consider using a better method for establishing these individuals do suffer with chronic fatigue. - Lynette Hodges

Statement from the study author, Esther Crawley

I did a press briefing because it was important to me that the limitations and implications of this study were clear. For example, it was important to me that children with CFS/ME [chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis] and their parents understood that we have only tested LP [Lightning Process] in addition to specialist medical care. And that we could not say anything about adults with CFS/ME. I wanted it to be clear that many eligible children did not take part and some said this was because they didn’t want LP. I think most of these points were picked up by the press and on the whole, I was pleased with the reporting.

Authors: John Malouff, Associate Professor, School of Behavioural, Cognitive and Social Sciences, University of New England