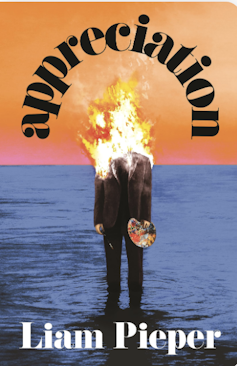

Vanity, money and ‘angry masculine impastos’: Liam Pieper’s Appreciation is a mordant tale of a tragically flawed artist

- Written by Georgia Phillips, Lecturer, Creative Writing, University of Adelaide

A nuanced exploration of the value and personal cost of art-making runs through Melbourne writer Liam Pieper’s jaunty new satirical novel Appreciation.

Set in the near present, the novel is about Oli – a gay painter from the country who has learned to capitalise on this fact in public appearances – while also reflecting on “toxic masculinity” in a vague, rote-learned way. Oli paints over-sized, Basquiat-inspired paintings, with “angry masculine impastos” and “rough impressionist wheatfields”. They have names in an Aussie battler idiom: “Daffo”, or “Thresher”.

Review: Appreciation – Liam Pieper (Penguin)

In the outer orbit of Oli’s universe lurks a flock of art “appreciators”. They are portrayed by Pieper as more interested in the long-term appreciating value of the works they’re bidding on than their artistic merits.

The struggle for artistic survival is the main conundrum at the heart of this mordant romp. Artists compete for a modest elite of buyers who in turn, despite their tastes (or lack of them), hold the keys to the wealth and enduring relevance of a select few (Oli being one of them).

Appreciation is Pieper’s fourth novel, (he has also ghostwritten bestsellers). His first, The Toymaker, a work of historical fiction, won the Christina Stead fiction award. His third, Sweetness and Light, deals with similar themes to Appreciation, including drug abuse, relationship breakdown, and an examinination of how larger systemic forces underpin personal relationships and the myths we make about ourselves.

Meeting the artist

Appreciation opens with a postmodern meta-reflection on the nature of story, before introducing our hero.

Oli has “just enough distinct elements to him”. He is in his early 40s. He drives a Toyota Hilux. He is a little too cavalier about his health, his life, and those around him. He has an incredible tolerance to recreational drugs and alcohol. Despite his recklessness, Oli is good-looking enough that nobody “has ever told him that the story of how he got his tattoo is not interesting”.

As Pieper writes, Oli

has a way of shuffling into the room like a very old dog, turning his attention on you, and in doing so lighting up your day.

Yet Oli is painfully conceited. At the start of the novel, he gazes at himself in the mirror, in a scene evoking the Baroque painter Caravaggio’s Narcissus. Like the painting, in which Narcissus is entranced by his own reflection, the novel continues in this self-regarding loop, with Oli embarking on a journey of scrutinising his own image.

Read more: Who was Narcissus?

Oli quickly trades his reflection in the mirror for perusing his social media platforms. As he scrolls, he harvests jolts of validation from followers who’ve deluded him into thinking “somewhere out there, he is loved”.

Several pages later, we discover how deep-seated Oli’s insecurities are when – despite his success, wealth and endless baggies (of cocaine) – he confesses his favourite sensation is being watched. Oli has no shortage of unlikable or even ugly qualities. Still, he does not eclipse the unlikability of Ottessa Moshfegh’s unnamed protagonist in My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018), a young woman who tries to chemically sleep for a year.

Read more: My Year of Rest and Relaxation: 'sad-girl' fetishism or 'cuttingly funny' feminist satire?

There is something to be said for Pieper’s exploration, in this novel, of the value of ugliness in contemporary art and its ability to challenge our existing conceptions of what we consider “good”. However, throughout the work, mentions of Oli’s art and art-making emerge as afterthoughts. This echoes the sense that his rise to fame has been less about his paintings, and more about personal brand-building.

Oli has forfeited so much – and received so much – for his artistic success he can no longer comprehend the true shape of what’s on the easel, or in the mirror before him.

Irony

Oli’s world is populated by two kinds of characters. There are those who are profiting off his success and working for him, such as his agent, Anton. And there are those who are trying to profit off his work through “appreciation”, such as buyers or The Paperman: a critic and arts editor of an influential broadsheet newspaper.

Anton, an old drug-dealer-cum-friend, plays a somewhat paternal role in Oli’s life, overseeing nearly all aspects of his livelihood. It is Anton who arranges Oli’s television appearance on a program “beloved by a left-leaning audience for its soothing politics”, which ultimately leads to his downfall.