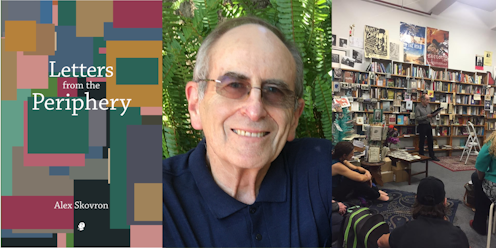

If you have ever been to the launch of a small-press poetry book at Collected Works bookshop (now defunct), or at one of the Readings bookstores, or at a bar or café in Melbourne, you may have seen a small, fit-looking, bespectacled man. He has a ready grin and eyes that invite you in – often to a conversation you’ll remember for its warmth, intelligence, wit and passion for literature.

You will have encountered Alex Skovron, who has this year won the Patrick White Literary Award for his achievements in poetry and prose and his lifelong support for writers and writing in Melbourne and beyond.

This prize is awarded to a writer who might not have received the recognition that is due when that writer’s full contributions and achievements are considered. Writers do belong to a community, even if it is fractured, fractious, garrulous and competitive at times. The community is best characterised, though, by acts of generosity towards each other, and Skovron has been a behind-the-scenes master of generosity towards other writers.

Author of seven books of poetry and three works of fiction, Skovron has previously won the Anne Elder and Mary Gilmore awards for a first book of poetry, the Wesley Michel Wright Prize for poetry (twice), John Shaw Neilson Poetry award (twice) and Australian Book Review (now Peter Porter) Prize for a single poem. His novella, The Poet, was co-winner of the Christina Stead Prize in 2005.

Skovron worked as an editor for two Australian encyclopedia projects during the 1970s, then from 1980 with publishers Macmillan, Hutchinson, Dent and finally, Houghton Mifflin. Alongside this work, his quiet and sustained impact on poets and poetry in Melbourne has been immense.

Hundreds of poets, especially the young and emerging, have been edited, mentored and encouraged by Skovron. It is common to pick up a new book of poetry in Melbourne and find his name there on the acknowledgements page. He has offered reliable and consistent support to others for decades.

Born in Poland in 1948 and arriving in Australia via Israel as a ten-year-old, Skovron’s cultural and intellectual reach has always been global.

His work has been translated into French, Chinese, Dutch, Polish, Spanish, Czech, Macedonian and German. He has worked with his Czech translator, Josef Tomáš on book-length translations into English of two 20th-century Czech poets and his latest book, Letters from the Periphery, includes his translation of the first canto of Dante’s Inferno.

Read more:

Guide to the Classics: Dante’s Divine Comedy

It is a shame poetry is not more widely read, enjoyed and appreciated in Australia. Skovron’s poetry has been wonderfully enriching, entertaining and provocative to its readers since his first published book, The Rearrangement, in 1988. His poems work attentively with shifts in tone and attitude, surprising line endings, pauses and rushes of thoughts and connections always towards an elegance toughened by life experience.

One poem, chosen almost at random, showcases these qualities:

For Light

If one is to be awoken by a cliché the clatter of breakfast dishes is as good as any, or the aroma of coffee freshly brewed, or that uncanny mood of holiday immensity, when the worldwas twelve, or a summer’s garden when the world

was good. Worst is the midnightphonecall, or the way the disentangled mindcan brood a black density into being – in the darknesses before seeing, lusting for light.

(from Towards the Equator: New & Selected)

His touch is light, his material is the experiences he knows and we do too and his feel for the drama lying in store for the most ordinary of us (living our clichéd lives) is somehow both seriously disturbing and finally settling.

He has been a poet who appreciates the largely unappreciated and passed-over aspects of workplaces, homes, marriages, streets and minds. So it is perhaps fitting he has now been recognised with a national award at 75. Perhaps at that moment in a life when a poet might think he has already passed unrecognised from most people’s view.

His poetry and his fiction surprisingly often turn to the Kafkaesque figure of an isolated everyman living slightly desperately but with an almost limitless potential for irony and humour.

One more poem offers a witty glimpse of this figure:

Homo Singularis

He would drive his car on the wrong sideof the seat, tried to obtain a licence to killtime, at work he displayed considerable skillat incompetence, at home he had to hidethe dismissal notes under the mattress he screwedto the carpeted floor with nails. Rude

he was to a fault, nosey to boot,inconsiderate to snails, he locked himself into booksof stamps and common prayer, funnelled his looksinto singles bars and hardly ever stepped footinside a song. Even his poems were too long.

(from Infinite City: 100 Sonnetinas)

To add to the detailed fun Skovron has with his compositions, we might notice the last line of this poem is its eleventh – in a book devoted to ten-line poems.

I would like to read, one day, Alex’s poem about this man receiving an award such as this.

Authors: Kevin John Brophy, Emeritus Professor of Creative Writing, The University of MelbourneRead more