The 'no' campaign is dominating the messaging on the Voice referendum on TikTok – here's why

- Written by Andrea Carson, Professor of Political Communication, Department of Politics, Media and Philosophy, La Trobe University

In the first week after the prime minister revealed October 14 as the Voice to Parliament referendum date, the “yes” and “no” campaigns recast their messages, resulting in unprecedented news coverage and public engagement with the debate.

Using data from Meltwater, a global media monitoring company, we are looking at the messaging and media coverage of the two campaigns. In the second report in our series, we identified more than one quarter of a million media mentions of the referendum on print, radio, TV and social media in week one – up 11.5% on the week before.

While that might sound like a lot – and it is – it still only constitutes 4.2% of all weekly media coverage in Australia. To put that in perspective, mentions of outgoing Qantas CEO Alan Joyce constituted 1.6% of total weekly coverage, while mentions of the AFL amounted to 2.2%.

What’s happening in the news

Australians woke up on September 3 to TV programs ringing out with John Farnham’s 1986 Aussie classic “You’re the Voice” as the soundtrack to the Uluru Dialogue’s new ad launching their “yes” campaign.

The night before, TV personality Rove McManus had hosted the ad launch in Melbourne. The packed crowd, some wearing T-shirts featuring the ad’s core message, “You’re the Voice,” cheered organisers Megan Davis and Aunty Pat Anderson and applauded songs from Paul Kelly, Jess Hitchcock, Mitch Tambo and The Farnham Band.

Farnham’s headline-grabbing gifting of his famous song – described by The Australian as a “titanic power ballad” – was celebrated by “yes” supporters. However, the ad (and even Farnham) faced a backlash from some of the “no” camp on talkback radio and social media. As La Trobe University historian Clare Wright, the instigator of engaging Farnham, posted:

Meanwhile, Opposition Leader Peter Dutton on Sky News competed with the Farnham scoop with his promise of a second referendum if the first one fails and the Coalition is elected.

Dutton’s pledged to return Australians to the ballot box to recognise First Australians in the Constitution, minus the Voice to Parliament mechanism. His timing was likely aimed at diverting attention from the “yes” campaign and eroding support for the constitutionally enshrined Voice by offering an alternative. He did this without the support of the Coalition’s Indigenous Australians spokesperson, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price.

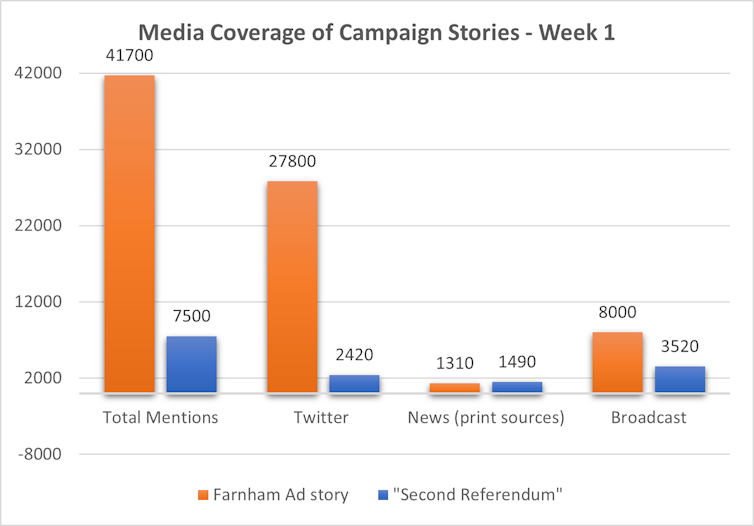

Tracking the impact of the two messages, we find the Farnham ad story far outpaced the “second referendum” in the free media sphere, as shown below.

What is happening in the polls

But despite the Farnham ad getting media traction (although not all positive), it has not stemmed the declining “yes” vote. That said, the next polls later this month will better capture the ad’s impact on voter intention.

Pooling the most recent commercial polls in a blog post on September 11, political scientist Simon Jackman calculates the “yes” campaign has fallen to 42.4% support nationally (with a margin of error of 2.2 percentage points), from 46% recorded in our first report.

To win, the “yes” campaign needs to get a majority of voters nationally and in a majority of states (four of six). This poll result is bad news for the “yes” side.

What’s trending on social media

The analysis of X (formerly Twitter) data shows the Farnham ad and “second referendum” stories also created a new high in public engagement about the Voice on the site this year.

This week, however, our focus is on the campaigns’ reach and engagement on TikTok.

According to TikTok’s 2023 data, its largest audience share is aged 18-24 and the second largest is aged 25-34. Together, these two age groups make up 71% of its global users.

While there are no public Australian age profiles of TikTok consumers, we know 8.3 million Australians aged over 18 use TikTok. Further, of Australia’s 26 million population, nearly one quarter (23.3%) are aged 18–34. With no reason to believe the Australian TikTok’s age profile is different to its global audience, TikTok is a logical space to reach younger voters with campaign messages.

We see the “no” campaigns recognise this and are having much greater engagement and visibility on TikTok than the “yes” campaign.

The right-wing activist group Advance Australia’s Fair Australia campaign topped the charts with the most views and engagements relating to the Voice coverage on TikTok (as seen in the Meltwater data) in week one. This is largely owing to Price’s TikTok, which garnered 1.2 million views and 83,100 likes.

To put this in a broader context, Fair Australia has attracted tens of millions of views of its Voice content since it started using TikTok in May.

While engagement does not necessarily impact voter behaviour, Fair Australia’s strategy is a direct attempt to influence younger voters who are far more likely to vote “yes”, according to some polls.

So far, Fair Australia is successfully engaging Australians on TikTok by combining volume (posting multiple TikToks a day) with three key elements:

authenticity (by prioritising Indigenous “no” supporters)

use of personal narratives

humour – especially by young adults for young adults.

In contrast, the two formalised “yes” campaigns, Uluru Statement (43,000 likes) and Yes23 (49,000) fail to get close to the top-viewed TikToks.

More generally, their content is noticeably different, relying heavily on news snippets and didactic speeches from prominent “yes” figures. While the “yes” campaigns have amassed 92,000 likes combined since they were created this year, they are well behind Fair Australia’s 860,000 likes.

Certainly, this is just one snapshot of an aspect of the campaign and tells us only so much. The major “yes” campaigns have strong followings on other social media sites (Facebook, Twitter and Instagram), and other “yes” supporters are individually posting to these platforms with varying success.

However, the formal “yes” campaigns lag noticeably behind on TikTok, a key social media platform for reaching young people.

This may be because the “yes” organisers feel confident about their strong appeal to the youth vote and are committing resources elsewhere. In any case, the “no” camp is pitching to this social media-savvy youth audience and is getting noticed.

Authors: Andrea Carson, Professor of Political Communication, Department of Politics, Media and Philosophy, La Trobe University