Grand design: why the AFL structure is unique – and has enabled competitive balance

- Written by Daryl Adair, Associate Professor of Sport Management, University of Technology Sydney

Since 2017, Victoria has commemorated AFL Grand Final Friday as a public holiday, with a parade of the two competing teams through a festive Melbourne (apart from interruptions in 2020 and 2021 due to COVID-19).

Saturday’s match between Geelong and Sydney is especially anticipated because it welcomes back the grand final to the MCG after a two-year absence due to local COVID restrictions. So, the packed stadium and associated entertainment promise to demonstrate renewal in the wake of the pandemic. It is also a celebration of a unique game, Australian made and owned, with a goal of competitive balance.

Made in Australia

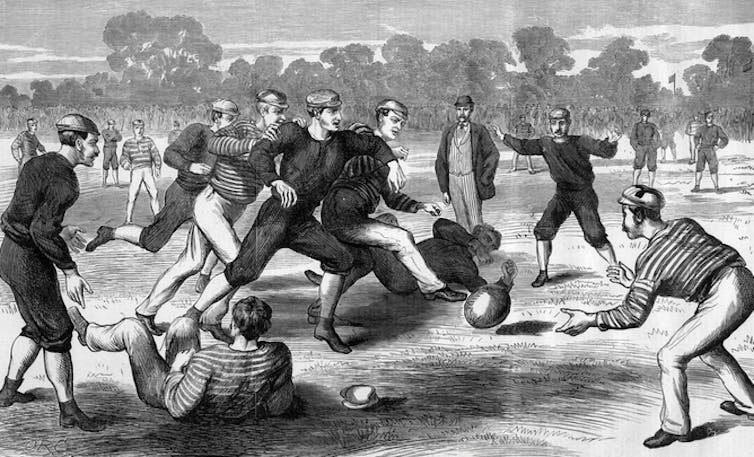

Australian Rules football, as the name suggests, is a substantial part of this country’s cultural fabric. It began as a pragmatic effort to keep Melbourne cricketers fit during cold winters in the 1850s. Rather than an invention, this game was more of an adaptation, as the colonists who drew up the initial rules (1859) took inspiration from various informal “kicking” and “handling” ball sports in Britain.

In that respect, although this Australian brand of footy evolved to become unique, it was not conceived as a challenge to imperial orthodoxy. Soon after, Association Football (1863) and Rugby Football (1871) were formalised in Britain, then transplanted around the empire.

The unorthodox aspect to this story is that, despite the import of soccer and rugby, the Australian game not only survived, it began to flourish in many parts of the country. That was unexpected: the colonists typically saw themselves as British subjects, paying homage to the cultural pastimes of the homeland. This game, made in Australia, was not part of the apron strings of empire.

But it was a colonial project. Indigenous people were often not welcomed to the sport in its development phase, and at the game’s elite level were all but absent until the last quarter of the 20th century. Despite this marginalisation, some believe the white man’s game of the 19th century was inspired by an Aboriginal cultural practice, Marn Grook.

It’s an unproven position, but a commonly touted explanation of how and why football was indeed “made in Australia”.

Read more: The long and complicated history of Aboriginal involvement in football

Owned by Australians

Globally, sport is being shaped by seemingly irresistible money and power. Competitions like soccer’s English Premier League epitomise private ownership and the demonstration of extraordinary wealth.

Most often, these owners are billionaires from abroad, for whom sinking money into a football club can be an indulgence. When Liverpool FC won the Football Association (FA) Cup in 2021, the trophy was held aloft by the club’s principal owner, the American John W. Henry, who flew in to mark the occasion.

In Australia, private ownership of football clubs is varied. Every A-League club and about one-third of NRL clubs are privately held, with a mix of local and foreign owners. Super rugby clubs have not experienced private ownership, though Rugby Australia is considering private equity investment to help alleviate its weak financial position.

In contrast, no AFL club is owned by entrepreneurs, nor is the league seeking to sell its well-funded competition to entrepreneurs. There were fledgling experiments with private owners at clubs, such as with the Sydney Swans and Brisbane Bears, but none lasted.

Today, AFL clubs are either member-based organisations or, in the case of very new clubs, run by the league until they reach a level of maturity.

Fan avidity is core to the success of the AFL. The league has long attracted large crowds, averaging around mid-30,000s since 1997. Additionally, some 1.19 million people are members of AFL clubs. Even though 25% of these fans don’t have attendance packages, they have a connection with a club and the sport.

In most clubs, full members have voting rights, though the corporate structure of these organisations has meant much more board control than democratic sway.

Whatever the case, these member-fans have more influence than followers of privately owned clubs, where entrepreneurs have operational control over their investment.

Structured for Australia

In England, soccer clubs participate in leagues that have long lacked regulations to establish competitive balance. Without equalisation measures like salary caps and draft systems, the winners of the Premier League title commonly reflect the financial power of club owners.

This is anathema to the AFL. For decades the league has endeavoured to limit the power of money over the competition by setting salary caps on players and soft caps on high-performance staff, and by distributing operational funds to clubs on a needs basis. The result of this is higher grants to “weaker” clubs.

Additionally, the AFL has borrowed from American sport a player draft system. The best young talent is first made available to poorly performed teams. Compared to the English Premier League, these design levers have provided hope for fans that their AFL team has a chance for success.

And it has largely worked. For example, between 1990 and 2010, 14 of the 16 clubs in that era tasted premiership victory.

This is not to suggest there are no structural problems. The AFL is contracted to showcase the grand final at the MCG, an arrangement that may disadvantage teams from outside Melbourne. There is also the question of fairness in the annual competition schedule, with critics asserting problematic variability across seasons.

Finally, on grand final day itself there is consternation that too few members end up with tickets while too many go to “corporate” guests, with the ratio roughly 70:30.

Of course, outside the ground, some 4 million Australians will tune into the free-to-air broadcast. May the best team win.

Authors: Daryl Adair, Associate Professor of Sport Management, University of Technology Sydney