To stop risky developments in floodplains, we have to tackle the profit motive – and our false sense of security

- Written by Brian Robert Cook, Associate professor, The University of Melbourne

In the aftermath of destructive floods, we often seek out someone to blame. Common targets are the “negligent local council”, the “greedy developer”, “the builder cutting corners”, and the “foolish home owner.” Unfortunately, it’s not that simple, as Sydney’s huge floods make clear.

In flood risk management, there’s a well-known idea called the “levee effect.” Floodplain expert Gilbert White popularised it in 1945 by demonstrating how building flood control measures in the Mississippi catchment contributed to increased flood damage. People felt more secure knowing a levee was nearby, and developers built further into the flood plains. When levees broke or were overtopped, much more development was exposed and the damages were magnified. “Dealing with floods in all their capricious and violent aspects is a problem in part of adjusting human occupance,” White wrote.

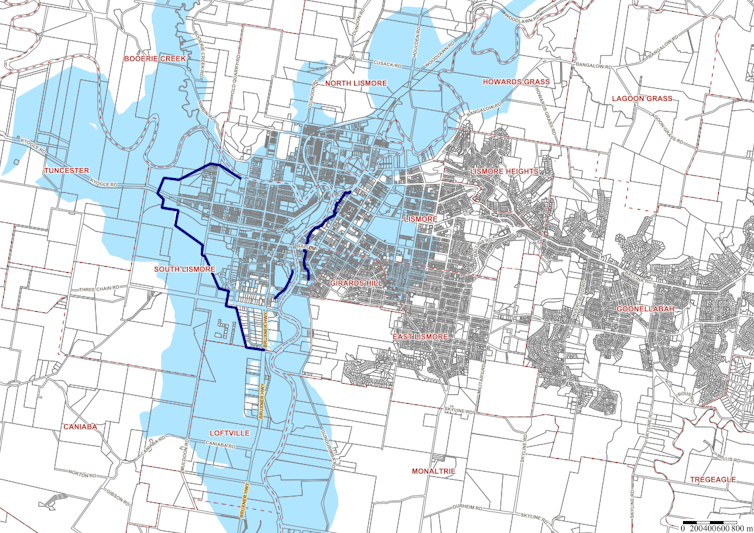

The levee effect shows why it’s so hard to reduce flood risk, even in areas hit hardest by this year’s record-breaking floods. The NSW town of Lismore had a 10 metre levee, experience dealing with many floods, and a flood risk management plan. It was devastated regardless.

To tackle flood risk, we have to respond to the social, political, economic, and environmental factors that drive development and occupation of floodplains.

Social factors: we love living near water

Around the world, people like to live near water – even if it might flood. Waterfront properties and those with river views command significantly higher prices. In addition, Australians view home ownership as a rite of passage, a key marker of adulthood as well as an economic investment. People will prioritise home ownership over concerns about living in a floodplain – especially when the house is part of a government approved development.

Political economy factors: money can drive decision making

Developing flood-prone areas generates profits, not just in monetary terms, but also through social and political capital. When developments are proposed, flood risk is assessed using the 1% annual exceedance probability line. This line, colloquially known as the 100-year flood event, defines land with a 1% chance of experiencing a flood each year.

The act of drawing this line creates more valuable and less valuable lands. Land owners on the boundary have an incentive to argue for change, sometimes based on how the 1% line is modelled. Developers can – and have – argued certain blocks should be acceptable for development. This can be appealing to local councils eager to encourage economic development and expand their tax base. When boundaries shift and less valuable land is converted into residential land, developers are rewarded with higher profits – while communities and future homeowners take a step closer to the next flood.

In some cases, like Lismore, developers building inside the 1% line are permitted to install mitigation measures, such as by infilling land, raising floor levels, building embankments, and installing large pumps. They are usually required to also build an additional 500 mm of freeboard above the 1% flood level.

Job done? Not quite. When a developer successfully argues for the redesignation of ‘flood-prone’ to ‘developable’, this sets a precedent that strengthens future development proposals. More developments create more risk, causing new flood control measures to be proposed, which are justified on the basis of encouraging more investment and development. The cycle continues.

When a developer converts flood-prone land into homes, they own the consequences a flood might bring to them. But when that building is sold, liability for flood damages is transferred to the new owner. It is common to portray such owners as naive or irresponsible, but they’re purchasing a home approved by the council on the basis of expert modelling.

The home owner pays their rates, like everyone else, and has every right to assume professionals have determined the safety of the development. When large-scale floods hit, those owners are as entitled as anyone to government assistance and relief.

This final act of goodwill – extremely difficult for any government to refuse – effectively shifts the costs of disaster mitigation, relief, and recovery to the Australian taxpayer. As John Handmer has argued, “flood risk is characterised by private sector profit while the costs are borne by the public sector, individuals and small business.”

Environmental factors: warping nature means more reliance on engineering

Floods are valuable, natural processes. In many farming regions, a bumper crop follows floods due to additional moisture and deposited nutrients.

But when parts of the environment are turned to concrete, the ability of the land to absorb flood waters drops and engineering protections become even more necessary.

Dams, embankments, storm drains, and pumps which protect developments are only effective to a point. Such structures effectively eliminate small scale floods, which would have otherwise helped to recharge aquifers, raise the level of “green water” stored in soils, deposit sediments, aid soil fertility, and prevent compaction and subsidence.

As a result, engineering solutions stop small-scale flooding and its accompanying benefits, while failing to prevent large-scale floods – and giving a false sense of security to floodplain residents.

What can be done?

To some degree, we’re all implicated in a system encouraging some people to profit by building flood-prone housing. When houses flood, it is the public who subsidises these developments with disaster relief and structural flood mitigation.

As climate change shifts the traditional boundaries of flood-prone areas, we face the pressing need to confront the forces driving us to develop floodplains.

A key first step is to harden boundaries and limit opportunities to ‘nibble’ into floodplains. Holding developers and builders accountable to home owners even after the sale would be beneficial, though such arrangements are virtually unprecedented.

Evacuation or abandonment of floodplains is inevitable. Lismore’s voluntary house purchase scheme is aimed at removing flood-prone structures inside the area prone to 1 in 20 year floods. Despite efforts like this, floodplain withdrawal has only succeeded a handful of times – and those gains are often quickly erased.

For now, Australians living in flood-prone areas should consider making their homes more flood-resilient to limit the impacts of small and medium floods, given these are likely to expand geographically due to climate change.

Nationally, Australia must tackle the hidden incentives causing encroachment if we are to avoid settling in areas where we cannot safely live.

Authors: Brian Robert Cook, Associate professor, The University of Melbourne