It's time for Australia to develop its own guided missiles — otherwise, we'll need to keep asking for the codes

- Written by Graeme Dunk, PhD Candidate, Australian National University

Step by step, Australia is inching its way towards more autonomy in defence.

On Wednesday, Defence Minister Peter Dutton was reported to have signalled greater access to US missile technology will be a key test of the US-Australia alliance at a closed meeting of the American Chamber of Commerce in Australia.

In March Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced the defence department would select an industry partner to develop a A$1 billion guided weapons manufacturing capability.

But, more than in earlier times, it’s the details that will matter.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Peter Jennings says a key lesson from the collapse of the US operation in Afghanistan is that its allies can no longer assume it will be just “over the horizon ready to defend our strategic interests”.

It was, he said, “a tough message for Australia, which has become habituated to think that defence spending at a little over 2% of gross domestic product and a defence force about two-thirds the size of a Melbourne Cricket Ground crowd is enough to defend the country”.

Japan seems to be also rethinking its strategy.

Four options: the best is expensive

There are four options for improving self-reliance in guided weapons.

The first is simply to buy more of what we currently have. It isn’t bad as a short-term approach, but we can’t guarantee we will have what we need, when we need it. Weapons can date and we can slip down the queue for replenishment — just think of COVID-19 vaccine supply.

The second option is to assemble in Australia, rather than simply import.

Read more: It's one thing to build war fighting capability, it's another to build industrial capability

This is better than the first option, and would create jobs. But jobs are hardly going to be the most pressing issue when the firing starts. And we are unlikely to get all of the intellectual property (the knowledge about how to build and repair) we might need to upgrade when circumstances change.

The third option is to use Australian industry to improve and replace some capabilities of current weapons with locally-developed alternatives.

Targeting software and counter-counter-measure software could be examples.

Read more: Australia's plan for manufacturing missiles to be accelerated

This option is better than the previous two options, but still relies on us having access to foreign (often US) intellectual property, which might be problematic.

The best option is to design and build our own guided weapons. This would be expensive, and it would require significant time, but it would actually make us self-reliant. We would own the intellectual property and own the codes.

We would be able to upgrade to take account of developments in technology and to account for changes in the adversary. We wouldn’t have to wait in line to be given an upgrade.

We will probably need all four options

This is not to suggest we need to develop every type of guided weapon type we would use. There are some where the integration issues would be profound if not close to impossible (the joint strike fighter is an example).

It isn’t that we need sovereignty in guided weapons, what is that we need smart sovereignty — smart in the sense that we focus our efforts and our money where we can get the most useful sovereignty.

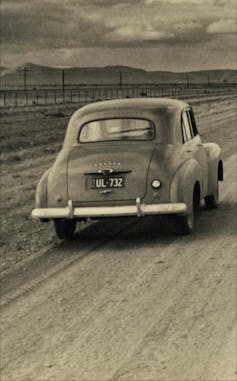

The Holden was the first car Australia made, rather than assembled.

State Library Victoria

The Holden was the first car Australia made, rather than assembled.

State Library Victoria

In some cases the sensible thing will be to buy and/or fabricate, just as Australia buys foreign cars and in the early days of manufacturing assembled foreign cars.

In others cases it will be to develop additional weapons locally. Each approach will be the best in different circumstances. We will probably need some of each, simultaneously.

But we need to take charge of our own destiny where we can, rather than just rely on a helping hand that may or may not come when we need it, or in the way we will need it.

We certainly can’t go toe-to-toe with our most likely regional adversary on our own. We don’t have anything like the capability.

But what we can do is target the development of local weapons to those that are likely to be of the most use against that adversary. Deployable, mobile, hypersonic anti-access/area denial guided weapons are among those that would help.

Waiting might leave us unable to choose

Irrespective of the option we choose, we will need to test the guided weapons we use domestically. This means developing in parallel a domestic capability for the modelling, simulation and analysis that will be critical to success.

Australian industry has the capability, but time is running short. The pandemic has shown us that the money can be found where the need is critical.

The future might not be kind to us but at the moment we still have time to choose the path to take. Later, that path might be dictated for us.

Authors: Graeme Dunk, PhD Candidate, Australian National University