Barbara Hanrahan: an Australian feminist artist you need to know

- Written by Melinda Rackham, Adjunct Research Professor, UniSA Creative, University of South Australia, University of South Australia

A palpable cast of women inhabit Barbara Hanrahan’s oeuvre, joined frequently by their “daddys”, sweethearts, valentines and husbands.

Given her father died the day after her first birthday, leaving Hanrahan (1939-91) to grow up with her maternal grandmother, mother and great aunt in Adelaide’s then working-class suburb Thebarton, it is no surprise the matriarchy dominates.

Innocent and audacious, her characters jostle, quiver and hum in this significant salon-hung survey at Flinders University Museum of Art.

180 works on paper — woodcuts, linocuts, screenprints, lithographs, etchings, dry points and rarely-seen drawings, paintings and collage — produce a shrine to Hanrahan’s bold visual language.

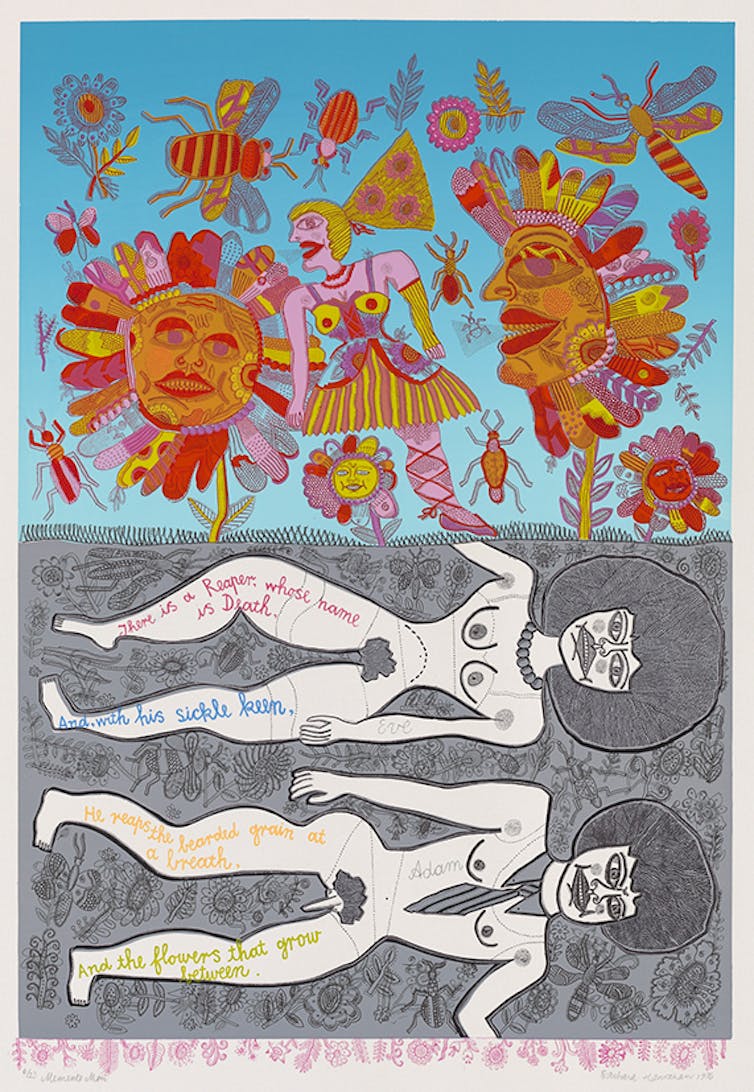

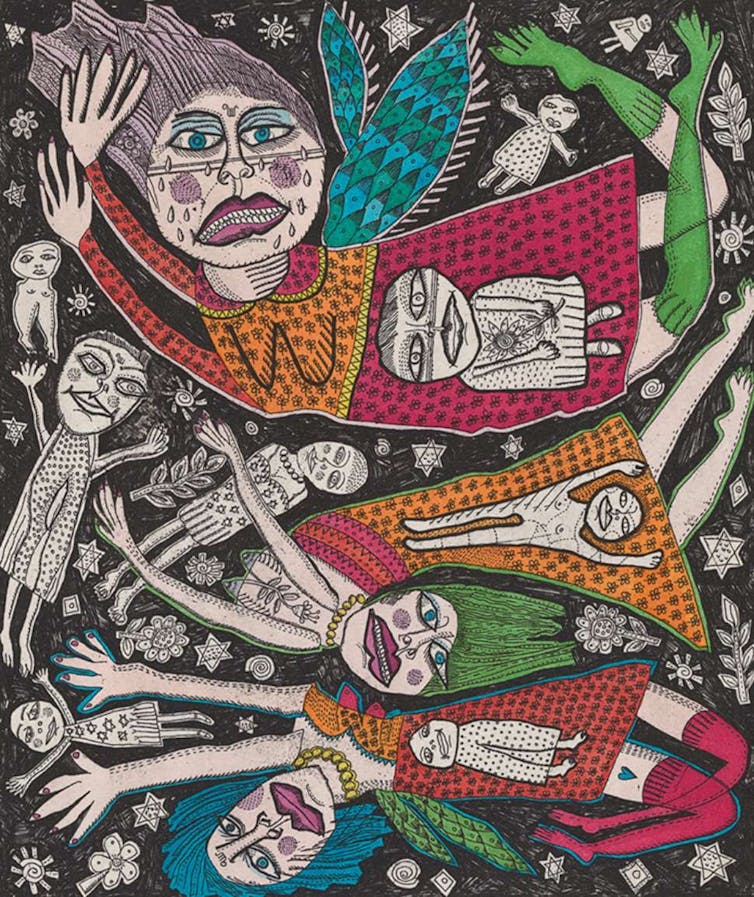

Barbara Hanrahan, Memento mori, 1976. Screenprint, colour inks on paper 60.4 x 42.4 cm (image), ed 6/23. Private collection, Adelaide.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Barbara Hanrahan, Memento mori, 1976. Screenprint, colour inks on paper 60.4 x 42.4 cm (image), ed 6/23. Private collection, Adelaide.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Their breadth and depth, texture and translucency demand an embodied engagement.

You have to get up close, stretch and bend, almost breathe the same air as the artworks you are observing.

This show asks to be savoured, to be given time to absorb the spice of conical breasted, gartered and corseted ladies; the biting sadness of torrential tears; the sour aftertaste of society’s hypocritical expectations; the sweetness of childhood memories.

An independent woman

Encouraged by her mother’s work as a commercial artist in a department store, Hanrahan originally trained as an art teacher.

After graduating in 1960, she enrolled in night classes at the South Australian School of Art, making her first linocuts, etchings and lithographs.

Independently minded and influenced more by the drama of German expressionism than Australian printmakers such as Margaret Preston, Adelaide Perry and Ethel Spowers, Hanrahan set off to swinging London a few years later to pursue her creative dreams.

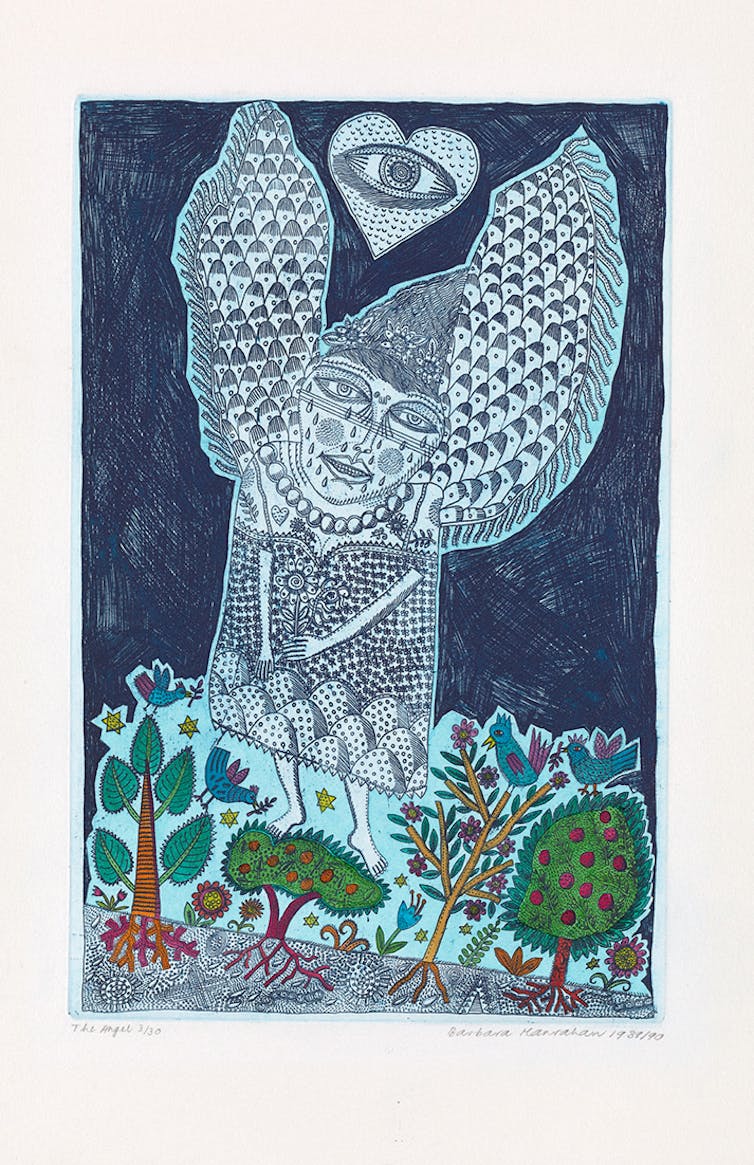

Barbara Hanrahan, The angel 1989-90. Hand-coloured etching, colour inks on paper, 34.8 x 22 cm. Private collection, Adelaide.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Barbara Hanrahan, The angel 1989-90. Hand-coloured etching, colour inks on paper, 34.8 x 22 cm. Private collection, Adelaide.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Gaining a taste for pop art and the burlesque, she was not so much a proponent of the Women’s Art Movement but worked in parallel, questioning beauty, social convention and sexual mores.

She regularly visited Australia to exhibit until returning to live in Adelaide with her partner in the late 1970s.

It seems quaint to recall that, in 1964, Sydney art dealer Barry Stern declined to show Hanrahan in his “family gallery” or, after purchasing many works, Adelaide gallerist Kym Bonython received legal advice not to exhibit her etchings of naked men.

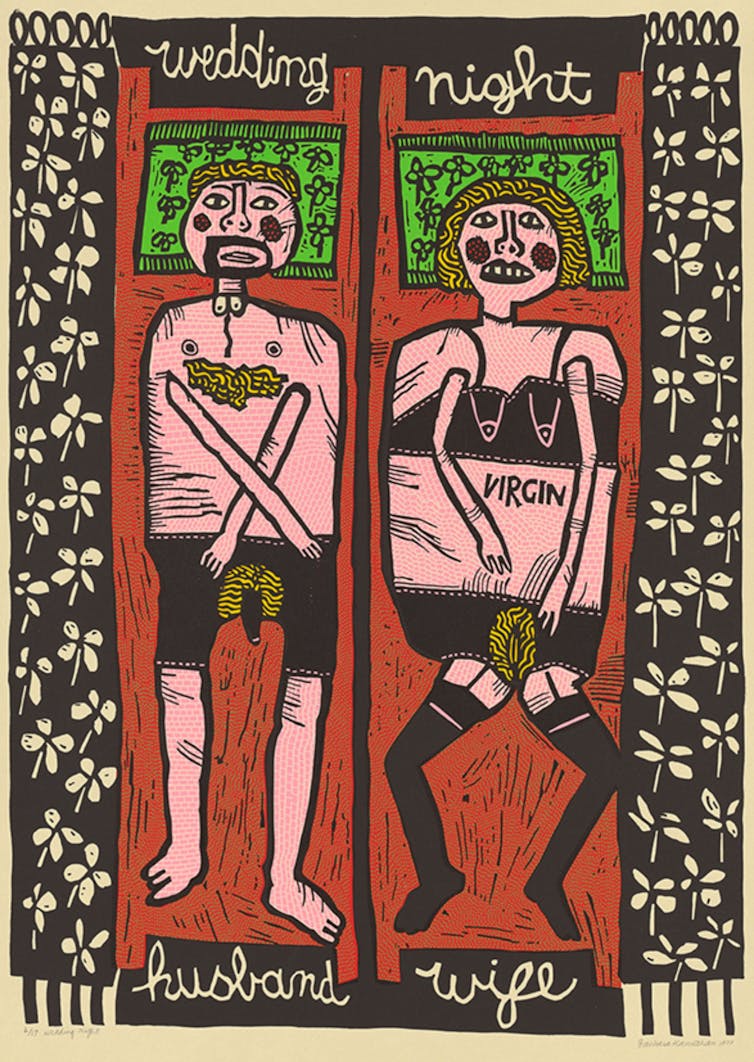

Australian women artists of her era such as “femail” artist Pat Larter and Charis worked with sexually explicit imagery in drawing, collage, photography and video. But Hanrahan’s characters are often unaware, naive, or — as in Wedding Night (1977) — very awkward.

Barbara Hanrahan, Wedding night, 1977. Screenprint, colour inks on buff paper, 64.5 x 46.7 cm (image), ed 2/17. Flinders University Museum of Art, Adelaide 5770.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Barbara Hanrahan, Wedding night, 1977. Screenprint, colour inks on buff paper, 64.5 x 46.7 cm (image), ed 2/17. Flinders University Museum of Art, Adelaide 5770.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

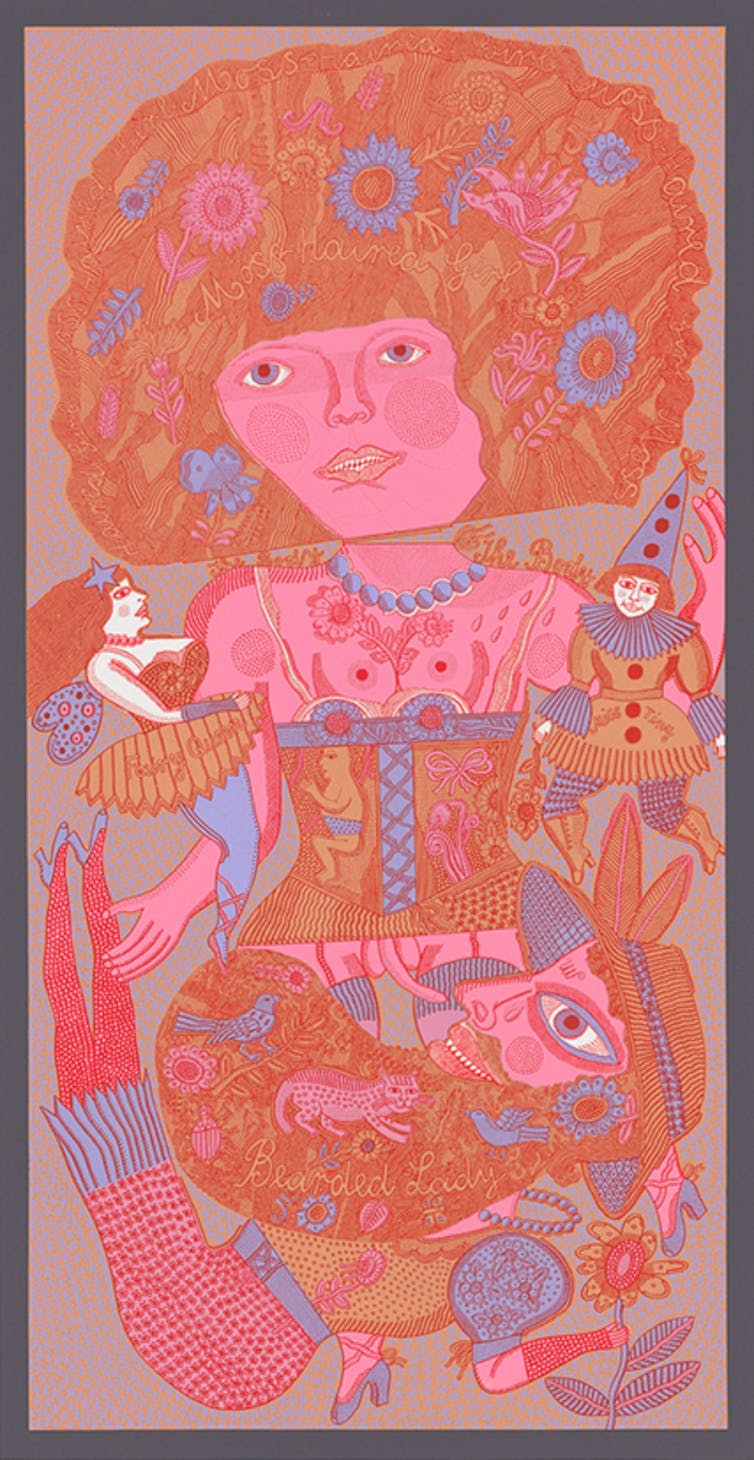

Ironically, while being labelled risqué, Hanrahan was simultaneously criticised for being too decorative in image and form, as if her technical excellence portrayed a shortcoming.

Her technical achievement is on stunning display here in etchings such as Earthmother (1975) and the perfectly registered multi-coloured screen prints like Moss-haired Girl (1977).

Barbara Hanrahan, Moss-haired girl, 1977. Screenprint, colour inks on paper, 63.3 x 33.1 cm. Gift of Jonathan P Steele, Flinders University Museum of Art, Adelaide 5769.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Barbara Hanrahan, Moss-haired girl, 1977. Screenprint, colour inks on paper, 63.3 x 33.1 cm. Gift of Jonathan P Steele, Flinders University Museum of Art, Adelaide 5769.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Life, and death

Hanrahan’s interspecies ecosystems are populated by celestial bodies and English and Australian flora and fauna.

Intertwining woman becomes tree, branches sprout from human trunks and crevices, vulvas filigree into flowers, birds nest in fibrous hair, a man lives in the moon, Adam and Eve frolic before the fall, angels float Chagall-like through troubled skies, women hover flower-strewn as Ophelia across the Serpentine in London’s Hyde Park.

Barbara Hanrahan, Jonathan P Steele (collaborating printer), Angels and children, 1989. Relief etching, ink on paper, 25.9 x 22.2 cm (image), ed 13/25. Private collection, Adelaide.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Barbara Hanrahan, Jonathan P Steele (collaborating printer), Angels and children, 1989. Relief etching, ink on paper, 25.9 x 22.2 cm (image), ed 13/25. Private collection, Adelaide.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

In her work, the flutter of the dove and buzz of the bee are as vital as the ebb and flow of the tides or the flowering of the sun: all grounded in the order and fecundity of nature and its cycles of life and death.

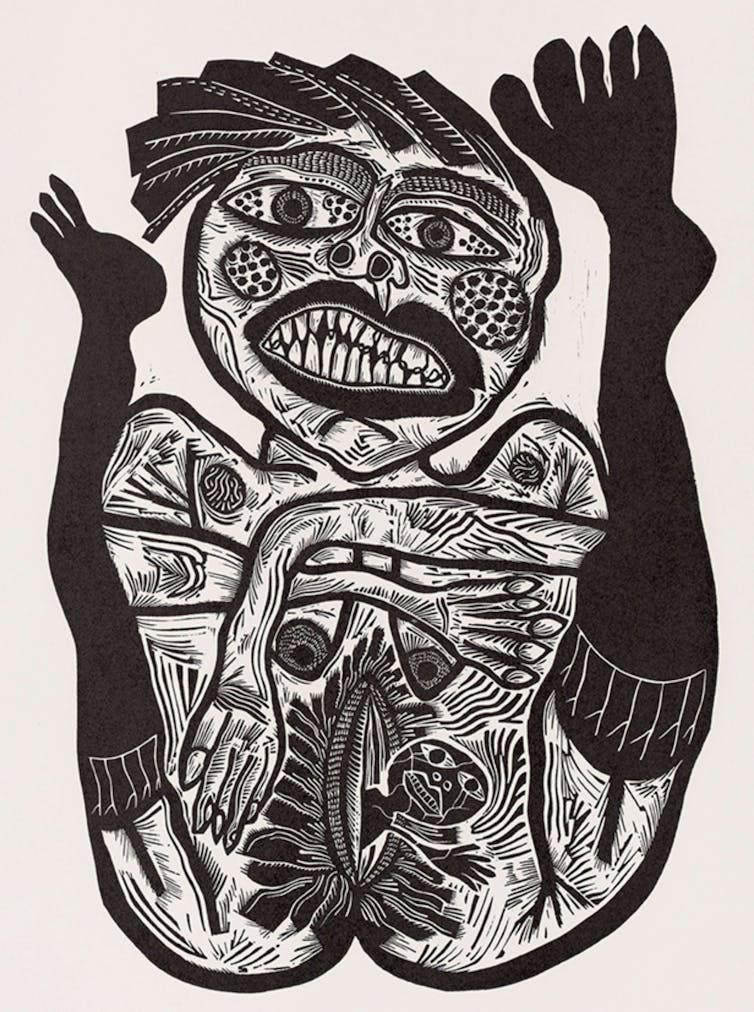

Twinning, mirroring and doubling reoccur. As with Frida Kahlo, Hanrahan has a fascination with birth, giving birth to the self, and self-realisation.

From her alarmingly unconventional linocut Birth (1986) to women depicted with fully formed children inside their belly or on their clothing, Hanrahan celebrates the curious inner-child we all carry with us.

Barbara Hanrahan, Jonathan P Steele (collaborating printer), Birth, 1986. Linocut, ink on paper 57.8 x 40.5 cm (image, irreg.), ed 16/25. Gift of Jonathan P. Steele, Flinders University Museum of Art, Adelaide 5768.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Barbara Hanrahan, Jonathan P Steele (collaborating printer), Birth, 1986. Linocut, ink on paper 57.8 x 40.5 cm (image, irreg.), ed 16/25. Gift of Jonathan P. Steele, Flinders University Museum of Art, Adelaide 5768.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris 2020

Abundant heart

Over three decades, Hanrahan revealed her adventurous, desiring, fragile, dreaming self in over 400 images and 15 books. Her work would frequently return to portrayals of her grandmother, Iris Pearl, and she continued to explore the psychological underbelly of family lineages and the diverse neighbourhood characters that impressed her childhood.

Barbara Hanrahan, Jonathan P Steele (collaborating printer), Girl with dogs, 1989. Linocut, black and red inks on paper, 62.5 x 36.5 cm (image, irreg.), artist’s proof. Private collection, Adelaide.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris

Barbara Hanrahan, Jonathan P Steele (collaborating printer), Girl with dogs, 1989. Linocut, black and red inks on paper, 62.5 x 36.5 cm (image, irreg.), artist’s proof. Private collection, Adelaide.

© the Estate of the artist, courtesy Susan Sideris

She exorcised the socially demonic forces of propriety, unbinding the constriction of gendered stereotypes and, through western and eastern spiritual practices, came to a peaceful acceptance of her own terminal illness.

Works produced in Melbourne in Barbara’s final years beat with an abundant heart. Celebrating her mastery of line and intelligence of touch, Girl with dogs (1989) and The Angel (1991) are iconic Australian images.

This ambitious survey is set to ensure Barbara Hanrahan becomes a household name.

Bee-stung Lips: Barbara Hanrahan works on paper 1960-1991 is online and on display at FUMA Gallery until October 1, before touring nationally.

Authors: Melinda Rackham, Adjunct Research Professor, UniSA Creative, University of South Australia, University of South Australia

Read more https://theconversation.com/barbara-hanrahan-an-australian-feminist-artist-you-need-to-know-166664