'Fit for service': Why the ADF needs to move with society to retain the public trust

- Written by Damian Powell, Historian and Principal, Janet Clarke Hall, The University of Melbourne

The Australian Defence Force has faced a reckoning in the past few months. First came the shocking Brereton report exposing alleged war crimes committed in Afghanistan.

Then, in recent weeks, other critical issues have surfaced requiring urgent attention, from the royal commission investigating veteran suicides to a vigorous debate over the very function of the ADF itself in today’s society.

As we prepare to withdraw our forces from the Afghan conflict without any consensus on the war’s outcomes, the ADF is potentially at a crossroads.

Not only are questions being raised about its culture, there appears to be a struggle underway about its identity and purpose, as well.

How the ADF has changed

A century ago, war correspondent and historian Charles Bean gave form to the idea that:

Anzac stood, and still stands, for reckless valour in a good cause, for enterprise, resourcefulness, fidelity, comradeship, and endurance that will never own defeat.

It has been a useful myth, and one that Australian soldiers continue to draw on in terms of their self-awareness and self-identity. It has also promoted civilian understanding of the potential sacrifice that lies at the heart of the ADF’s service ethos.

But it has clear limitations in the modern context of war fighting, among them:

no awareness of the highly technical realities of modern warfare

little recognition of women, whose technical and counterintelligence capabilities are of equal or greater importance than men in some specific military roles

an emphasis on the mythic bonds of (primarily Anglo-Celtic) mateship forged through combat, turning men into marble statues devoid of human frailty.

An opportunity to rethink core values

The Brereton report has provided an opportunity for the ADF to rethink its core values and what it stands for. And it must keep in mind that in the age of social media, it is hard to hide — or forgive — a shadowy side of any institution which holds public trust.

Chief of Defence General Angus Campbell showed in his pained response to Brereton that our military is no different to any other institution in this regard. It needs social trust — including the trust of those young people who are the only source of its future human capital.

Campbell offered an apology for ‘any wrongdoing by Australian soldiers’ in Afghanistan.

Mick Tsikas/AAP

Campbell offered an apology for ‘any wrongdoing by Australian soldiers’ in Afghanistan.

Mick Tsikas/AAP

This doesn’t mean the military needs to be more “woke”, to borrow a phrase from Liberal backbencher and former soldier Phillip Thompson. It means corporate, political and educational leaders ignore changing social expectations at their peril.

Behaviour once able to be brushed under the carpet or brushed off as a joke is now a potential “career killer”, as social trust (and economic capital) flows away from institutions and their leaders who are deemed to be out of step with social mores.

Read more: Why Australian commanders need to be held responsible for alleged war crimes in Afghanistan

Young Australians may still come out for ANZAC Day marches, but they are equally — if not more — passionate about the “Black Lives Matter” movement and the struggle for gender equality. And they’ll judge the military by how responsive it is to these and other social issues.

As Assistant Defence Minister Andrew Hastie reminded us last month, the military’s core task is using lethal violence in the national interest. Hastie’s emphasis on the application of lethal violence should not be discounted: it represents the sharp end of military capability.

‘Lethal violence’ does remain a core mission of the military, but it must also be used ethically.

Australian Department of Defence/PR Handout

‘Lethal violence’ does remain a core mission of the military, but it must also be used ethically.

Australian Department of Defence/PR Handout

In the end, though, the ADF’s greatest asset is its people. For the best and brightest to be attracted to military service, the application of “lethal violence” must also be lawful and the ethical case for using such violence well understood.

The public also sees the role of the ADF as going beyond war fighting. Here, recent contributions made by defence personnel in the pandemic, alongside bushfire and flood recoveries, have promoted productive layers of community engagement.

As the ADF has drawn on the wide skill set offered by part-time, reserve personnel — supported by defence logistics and command structure — civilians have seen the military working on the ground as engineers, doctors, nurses and in other professions ranging from arborists to veterinarians.

The ADF’s bushfire response shows how to build trust in communities.

Department of Defence/AAP

The ADF’s bushfire response shows how to build trust in communities.

Department of Defence/AAP

Why reviews can bring lasting change

Successive reviews of military culture make clear the challenges. To ensure its capability, the ADF needs to stay focused, relevant and off the front pages of the papers by addressing poor cultural practice.

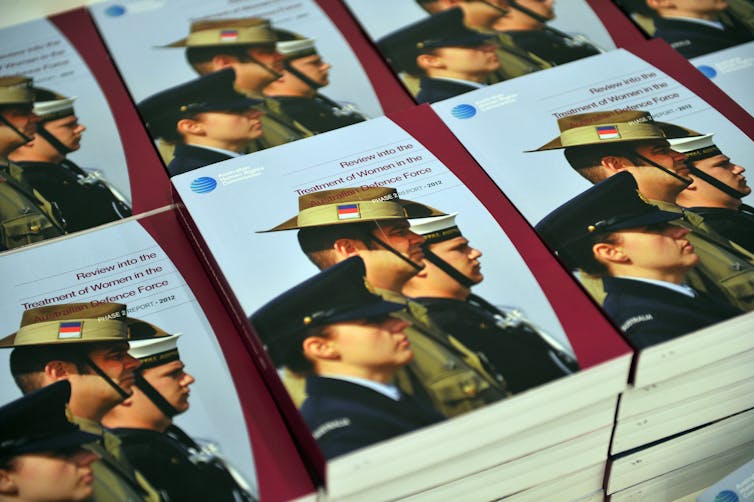

It seems reasonable to assume the ADF – perhaps our most valued national “brand” – has the capacity to take the lead in good cultural practice. It did so in owning and then building on the recommendations of the Broderick reviews into the treatment of women in the military.

While far from uniformly popular among service personnel, this put the ADF ahead of society at a time when it threatened to fall badly behind.

Elizabeth Broderick led a thorough review of sexual harassment and assault in the military nearly a decade ago.

Paul Miller/AAP

Elizabeth Broderick led a thorough review of sexual harassment and assault in the military nearly a decade ago.

Paul Miller/AAP

Indeed, one of the unresolved questions from the Broderick reviews - the extent to which the Australian Defence Force Academy reflected university culture in terms of its treatment of women - fostered a conversation that led, indirectly, to the Australian Human Rights Commission’s “Change the Course” report on sexual harassment on campus.

Vice chancellors and generals alike now find themselves accountable for ensuring a respectful culture for women across the country.

There is no reason why defence cannot lead future discussions on good practice in all its facets, from war fighting to leadership training.

The Brereton report showed the ADF is willing to subject itself to public scrutiny, and to be judged by the standards it demands of our men and women in uniform. With proper sensitivity towards the effects on our service personnel, we need an honest, open discussion, leading to honest conclusions, about our military conduct in Afghanistan.

We must also examine what we need to do better to train, support and supervise our troops.

The goodwill of the nation depends on it

For the ADF to focus on its primary mission of war fighting, it needs strong morale among its troops. For that, it needs the goodwill of the nation.

Any misalignment of defence values with societal expectations could lead to an eventual dead end – in promoting, recruiting and maintaining a cultural identity without parallel in Australian society.

Read more: Crowds at dawn services have plummeted in recent years. It's time to reinvent Anzac Day

Some years ago, when addressing a group of ADFA recruits, I was challenged by an officer cadet who claimed the Broderick review team risked turning the Army into the “boy scouts”.

His inference, I assume, was that by addressing a toxic culture in which women were at times objectified and mistreated, we ran the risk of destroying a culture of masculine aggression and fraternity needed in combat.

My response was, above all, that Australia needed its defence forces to maintain their war-fighting capability. To do that, the country needed a great deal of trust, and clarity, around what is required — morally and culturally – of those who are tasked with carrying out lawful violence in our name.

In an age in which individualism is so highly promoted and prized, clarity of expectation and role within the ADF is more important than ever.

Authors: Damian Powell, Historian and Principal, Janet Clarke Hall, The University of Melbourne