From fireballs in the sky to a shark in the stars: the astronomical artistry of Segar Passi

- Written by Duane W. Hamacher, Associate Professor, The University of Melbourne

When Uncle Segar Passi watches the position of the setting Sun from his front patio, he notes its location and relates that to the time of year and changes in seasonal cycles.

What he sees translates into his artworks. They are visually stunning, a rich tapestry of colours jumping off the frame with a palate that easily rivals Vincent van Gogh. This is reflected in the many awards he has garnered over the years.

Lidlid by Segar Passi (2011)

Queensland Art Gallery

Lidlid by Segar Passi (2011)

Queensland Art Gallery

His artistic talent is matched only by the depth of his wisdom and cultural knowledge, which he teaches through his practice.

An island home

Turning 79 this year, Uncle Segar is a senior Meriam elder and a Dauareb man, meaning his community is originally from Dauar, the larger of the two small islands off the coast of Mer (the other being Waier) in the eastern Torres Strait.

The volcanic trio of islands are collectively known as the Murray Island group, and sit at the very tip of the Great Barrier Reef.

The Murray Island group in the eastern Torres Strait: Mer (foreground), Dauar (upper right) and Waier (upper left).

Duane Hamacher

The Murray Island group in the eastern Torres Strait: Mer (foreground), Dauar (upper right) and Waier (upper left).

Duane Hamacher

Professor Martin Nakata, a Torres Strait Islander and Pro-Vice Chancellor at James Cook University, brought me to Mer years ago to help the community document its star knowledge for education and community programs.

We stood on the beach near Uncle Segar’s house, watching the sunset near the double-hilled island of Dauar when he told me:

That place has powerful magic. If you want to learn about traditional star knowledge, you ask those elders. They’re the big dogs.

Looking to the artworks on the wall in Uncle Segar’s workshop, I noticed a plethora of subtle characteristics encoded within each one.

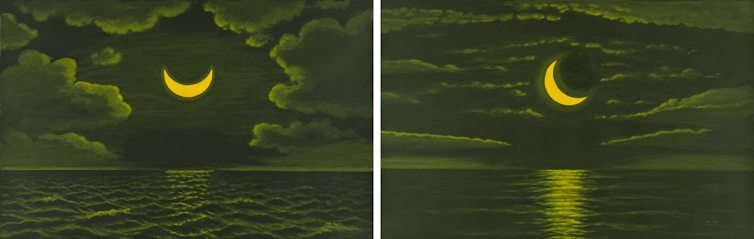

I know his artistic style is unique and aesthetically gorgeous, but I also know that every colour, brushstroke, motif and design has meaning. I see a painting showing a crescent Moon with the cusps pointing up. Above it are puffy cumulus clouds and the moonlight reflected in the choppy waters.

Kerkar Meb I (Left) and II (right), 2011. These paintings by Segar Passi show the changing orientation of the crescent Moon, which informs seasonal weather patterns.

Segar Passi. QAGOMA, Brisbane.

Kerkar Meb I (Left) and II (right), 2011. These paintings by Segar Passi show the changing orientation of the crescent Moon, which informs seasonal weather patterns.

Segar Passi. QAGOMA, Brisbane.

Another painting, which looks nearly identical from a distance, shows the Moon tilted at an angle. The clouds above are cirrus, and the reflection of moonlight is clear and strong on the calm, still water.

In his characteristic soft voice, Uncle Segar explained the meaning behind this pair of paintings.

Every month there is a New Moon at a different angle. Did you ever notice this?

He explained how the New Moon (kerker meb) can tell you about the changing seasons if you look at the angle of its tilt. When the cusps are pointing up (Meb metalug em), it is the dry season, the Sager.

You will see large cumulus clouds in the evening sky and the water is choppy. When the cusps point at an angle (Meb uag em), the water is calm and you see cirrus clouds. This is the wet monsoon season, the Kuki. He pointed to the painting:

If the water looks rough and the Moon is pointed up, you know the winds will die down and the next day the water will be fine.

The art of knowledge

The paintings are a medium through which complex systems of knowledge are passed down. These systems are based on generations of collective observation, deduction and interconnection – a longstanding system of science.

Read more: The Moon plays an important role in Indigenous culture and helped win a battle over sea rights

Uncle Segar is an expert on clouds and weather, the plants and animals, the sea, land, and the sky. His knowledge is as deep as his artworks are captivating.

The self-taught artist developed his style in the 1960s and has since won several major awards for his work, gaining an international profile through his raw talent, complex works and lovely personality. But his passion is for local community, both on Mer and across the Torres Strait.

Uncle Segar’s work has appeared in local school books and seasonal calendars about traditional knowledge. He has also worked closely with me and other academics over the years, sharing Meriam Star Knowledge and co-authoring several research papers.

These include publications about traditional ways of interpreting the twinkling stars, the role of astronomy in song and dance, and the relationship between bright meteors and death rites in the Torres Strait.

Uncle Segar is currently contributing to a major book on Indigenous astronomy for a global audience and has been featured in recent Indigenous astronomy articles in Cosmos magazine. His knowledge has even been written into the Australian National Curriculum for schools across the country.

The flying spirits

This knowledge has found its way into films by some of the world’s most critically acclaimed directors. Members of the Mer community performed the Maier (Shooting Star) dance for the 2020 Werner Herzog and Clive Oppenheimer film Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds.

Fireball, Visitors from Darker Worlds.Maier is a term from the Meriam Mir language referring to fireballs (exceptionally bright meteors), which are seen as a celestial personification of a recently deceased person’s spirit flying to Beig, the land of the dead.

The brightness, trajectory and sound of a Maier all have special meaning. If the Maier breaks into fragments and you see sparks fall (uir-uir), you know that person left behind a large family.

The trajectory of the Maier tells you where that person is from. And when you hear the booming sound (dum) as the fireball explodes, it tells you that person has arrived at their destination.

The Maier dance is originally from Mer but had not been performed on the island since 1969. In late 2019, the community approved Herzog and Oppenheimer to film the dance on Mer.

Led by Meriam elder Alo Tapim, four local dancers were taught the kab kar (sacred dance) and performed it on the beach at sunset just hours later, with cameras rolling. The segment you see at the end of the film is the first time the dance had been performed on Mer in 50 years.

A ‘Behind-the-Scenes’ photo of the community performing the Maier Dance on Mer at dusk for the film ‘Fireball’ in 2019.

Duane Hamacher

A ‘Behind-the-Scenes’ photo of the community performing the Maier Dance on Mer at dusk for the film ‘Fireball’ in 2019.

Duane Hamacher

Name in the stars

In 2020, his lifetime of work and his contributions to astronomy were recognised when the International Astronomical Union renamed the asteroid “1979 MH4” as “7733 Segarpassi”.

This is a 1.9km-wide asteroid in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It is 2.4 times farther from the Sun than Earth is, and takes 3.7 years to orbit the Sun.

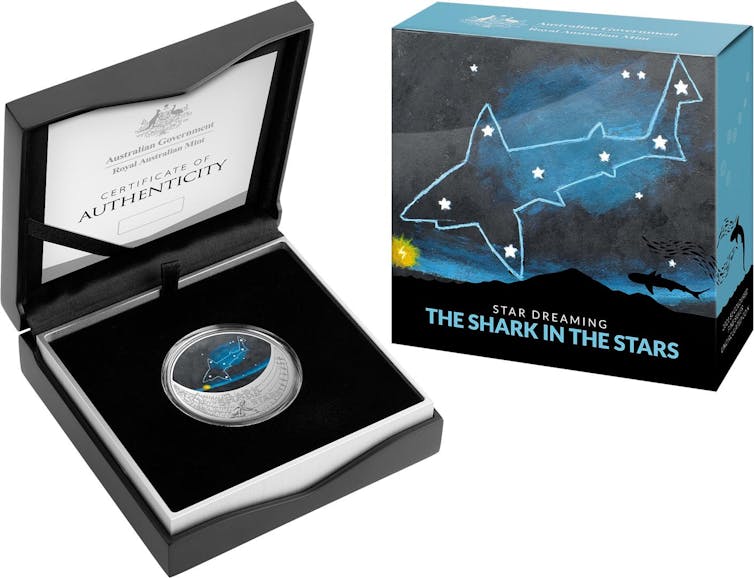

Uncle Segar’s important contributions to culture and science are also encapsulated in the newly released commemorative coin “The Shark in the Stars”.

Released on March 4, 2021 by the Royal Australian Mint, this non-circulating coin features Uncle Segar’s artwork. It is the third and final instalment of the Star Dreaming series, and was so popular all 5,000 coins sold out within two hours.

Beizam, the Shark in the Stars. Uncirculated $1 coin released by the Royal Australian Mint.

Royal Australian Mint

Beizam, the Shark in the Stars. Uncirculated $1 coin released by the Royal Australian Mint.

Royal Australian Mint

The celestial shark is called Beizam, a Meriam constellation formed by the bright stars of the Big Dipper (part of the Western constellation Ursa Major, the Big Bear). It traces out the head, body, fins and tail of the shark.

The changing position of the shark in the northern skies throughout the year is a seasonal marker that notes shifting seasons, when to hunt turtle, when to harvest yams, and informs the observer about the behaviour of the shark itself.

Read more: New coins celebrate Indigenous astronomy, the stars, and the dark spaces between them

When the nose of Beizam touches the horizon at sunset, sharks are feeding on sardines that swim in tight ribbons close to the shore. This occurs during the Sager, which can be a dangerous time to go for a dip.

Later in the year, as the shark dives below the horizon at dusk, you will see the first lightning of the coming monsoon.

Meriam people teach that water rushes through Beizam’s gills as it dives into the sea on the horizon, casting water into the sky which falls as the rains of the wet season, the Kuki.

Uncle Segar Passi continues to share his knowledge with the world, benefiting his community and the next generation of Meriam scholars. And we are exceptionally lucky and honoured to continue learning from Elders like him.

Read more: A shark in the stars: astronomy and culture in the Torres Strait

Authors: Duane W. Hamacher, Associate Professor, The University of Melbourne