Clean energy? The world’s demand for copper could be catastrophic for communities and environments

- Written by Deanna Kemp, Professor and Director, Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, The University of Queensland

The benefits of switching to clean energy are huge. As with any industrial activity, the transition has potential environmental and social impacts.

As we head towards net-zero emissions, record quantities of copper will be required. Copper is critical for solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles and battery storage.

Unfortunately, we’re headed for a supply crunch. Market analysts estimate the annual copper supply shortfall could be as high as 10 million tonnes by 2030 if no new mines are built. This means prices are on the rise, giving miners an incentive to bring new copper mines to market.

The complexity of these new mines will be unprecedented. Unless mining is done differently, rushing to bring these projects into production could unleash unacceptable, catastrophic impacts onto local people and environments.

A golden age for copper

Until recently, the copper market has been flat. Prices have been low, and it has not been a good environment for producers. The market is now on the move.

The demand for copper and other energy transition minerals has sparked predictions of a commodity boom, and a golden age for mineral exploration.

As an efficient electrical conduit, copper is required for many renewable energy systems including solar and wind power.

AAP Image/Supplied by Granville Harbour Wind Farm

As an efficient electrical conduit, copper is required for many renewable energy systems including solar and wind power.

AAP Image/Supplied by Granville Harbour Wind Farm

On April 12-13, major producers including BHP, Rio Tinto and Anglo American will convene for the World Copper Virtual Conference to gather market intelligence.

But in the face of high global demand, it’s critical these big companies don’t gloss over copper’s sustainability challenges.

4 major sustainability challenges

There are four major challenges the mining industry faces in the impending copper boom. How well these challenges are overcome will determine who wins and loses in the energy transition.

1. Unearthed copper deposits are locked up in remote and difficult locations

Unearthed copper deposits — known as “orebodies” — are often found in places such as the high Andes, the Arctic, and the deep sea.

The social, environmental and technical challenges of projects in these locations will be greater than before. For example, BMW, Samsung and Volvo have just backed calls for a moratorium on deep sea mining.

2. Many proposed projects face public opposition

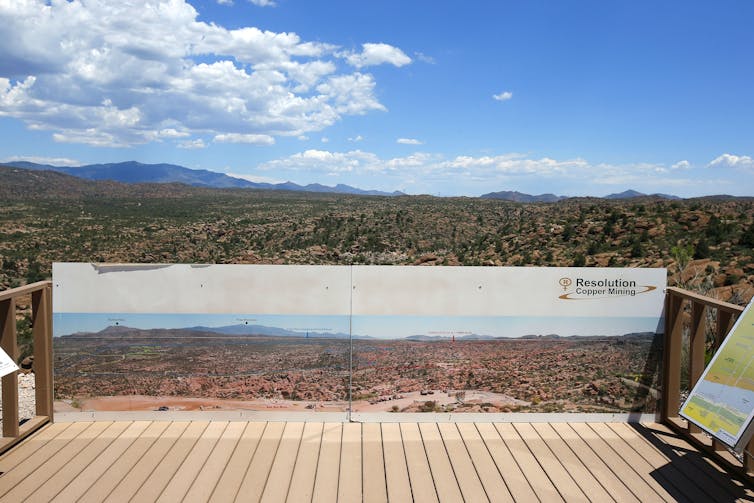

This includes major projects such as Resolution Copper in the US, Pebble in Canada, Tampakan in the Philippines, and Frieda River in Papua New Guinea.

Public opposition towards these and other large-scale copper projects means they could face difficult legal battles before these projects are permitted to go ahead.

Part of the Resolution Copper Mining land-swap project in Arizona, US, has had serious pushback from a group of Apaches, who sued the US government in January 2021.

AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin, File

Part of the Resolution Copper Mining land-swap project in Arizona, US, has had serious pushback from a group of Apaches, who sued the US government in January 2021.

AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin, File

3. Future copper mines are projected to be lower grade and deeper

Grade is a measure of the how much valuable metal there is in the ore body (deposit). Deeper, lower grade orebodies means new copper mines are likely to generate more waste rock, more tailings, and hazardous elements such as arsenic.

Read more: World-first mining standard must protect people and hold powerful companies to account

Tailings are the residues from mining and minerals processing, and is made up of finely ground rock, chemicals and water. If the projected demand is met, we calculate the world will produce more than nine times the amount of copper tailings between 2000 and 2050, than in the entire century prior.

Meanwhile, the industry faces a crisis of credibility over its management of this hazardous waste.

4. New copper mines will likely be located in politically and ecologically sensitive areas

Our research from 2019 found 65% of copper ore bodies that haven’t been mined are in areas with high water risk: too little water means miners compete for it among other local water users, and too much means waste can be difficult to contain.

Almost half (47%) of these ore bodies occur on or close to Indigenous peoples’ lands, and 64% within or near areas critical to biodiversity conservation. 50% are in socially and politically fragile countries, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo.

A simple price rise won’t solve major issues

In the past, the mining industry has relied on rising prices to address supply shortfalls. Higher metal prices give companies the financial capital they need to operate in difficult locations and invest in new mining technologies.

Some of this capital will support sustainability improvements, such as recycling and reductions in water and energy use. But many of the sustainability challenges we’ve outlined above are not price sensitive.

Read more: A brutal war and rivers poisoned with every rainfall: how one mine destroyed an island

Mining companies cannot pay their way out of biodiversity loss, extreme poverty, and corruption risk. If they don’t engage these big challenges before the copper boom gets underway these impacts will be baked in mining’s future legacy, without clarity about who takes responsibility in the long term.

This would add to the devastating impacts existing mines have already caused. One famous example is the Panguna mine in Bougainville, which led to massive environmental damage and triggered a civil war.

The Panguna copper mine in Bougainville sparked a decade-long civil war.

AAP Image/Ilya Gridneff

The Panguna copper mine in Bougainville sparked a decade-long civil war.

AAP Image/Ilya Gridneff

What’s more, intensifying social and environmental impacts of copper mines could jeopardise the long-term supply of copper. If opposition grows, and supply stalls, then so too will the clean energy transition.

So what are the options?

As demand for copper moves into overdrive, we are at a crossroads.

One option is to support large-scale copper mining and the clean energy transition for the greater good of the planet. Miners would do their best to minimise impacts, but we’d accept there’ll be collateral damage for local communities. This is far from the latest commitment to “zero harm to people and the environment” that the world’s largest companies recently made to tailings management.

Read more: Renewables need land – and lots of it. That poses tricky questions for regional Australia

A second option is to insist miners exhaust all opportunities to avoid harm. This is because sacrificing the interests of local people in the interests of a greater good would not be considered responsible, as it does not align with the concepts of equity and fairness that underpin the Paris Agreement.

This second approach would require significant improvements in managing social and environmental impacts of copper mining. It may also mean reducing global demand for copper, finding substitutes, and making hard choices about not developing mines if the risks to local people and the environment are too high. Doing this would require a wholesale restructuring of the function of global commodity markets.

We may not yet have a solution, but as the world prepares for this year’s major Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, we must start to ask: what kind of justice are we seeking in the “just transition”, and for whom?

Read more: Why most Aboriginal people have little say over clean energy projects planned for their land

Authors: Deanna Kemp, Professor and Director, Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, The University of Queensland