New Zealand's COVID-19 stimulus is a 'lost opportunity' to move towards a low-emissions economy

- Written by David Hall, Senior Researcher in Politics, Auckland University of Technology

In every crisis there is opportunity. Even during New Zealand’s strictest COVID-19 lockdown last year, many people felt the pandemic offered a chance to tackle other global crises, especially climate change.

The government responded to the pandemic with an extraordinary package of monetary and fiscal stimulus, most notably a NZ$50 billion allocation to the COVID-19 response and recovery fund.

But did the government embrace the call to “build back better” by directing that stimulus toward the low-emission economy or have these financial flows favoured carbon-intensive incumbents, locking us into an economic system implicated in making pandemics and other disasters more probable?

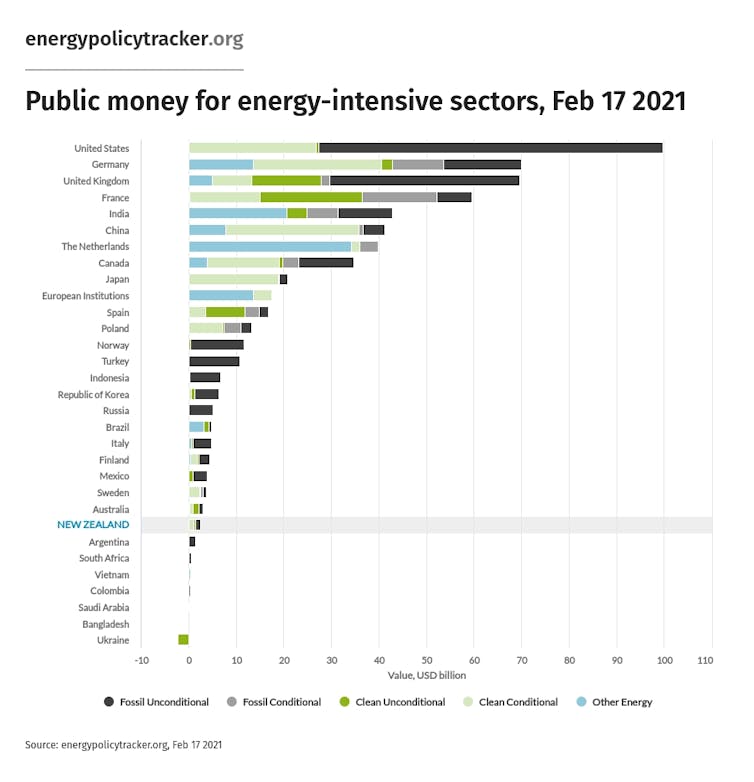

We partnered with international research network Energy Policy Tracker (EPT) to compare New Zealand’s response against other major countries.

We found New Zealand sits in the middle of the pack, with room to improve for future policy.

Energy Policy Tracker, CC BY-ND

The good and bad of energy policy

The Energy Policy Tracker focuses on energy policy but excludes other sectors, such as land use or adaptation. It classifies COVID-19-related funding according to energy type, and it uses three buckets:

policy that supports the fossil fuel economy

policy that supports clean energy

and policy that supports other energy, such as nuclear and biofuels.

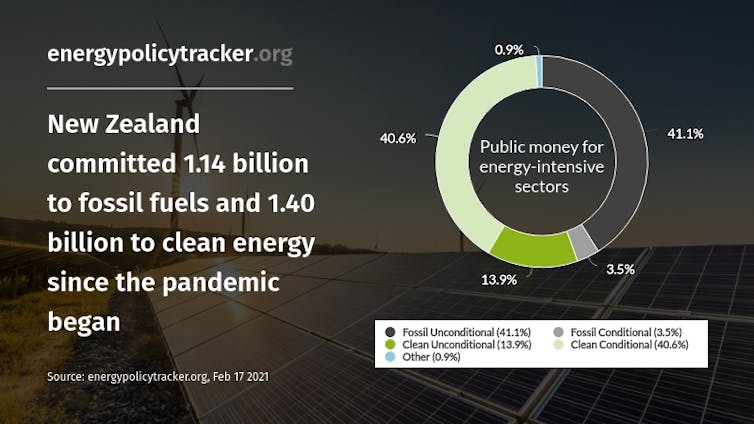

The overall balance for Aotearoa New Zealand was 44.6% fossil fuel-related, 54.5% clean energy, and less than 1% other energy. By global standards, that is a fairly middling performance.

Energy Policy Tracker, CC BY-ND

The good and bad of energy policy

The Energy Policy Tracker focuses on energy policy but excludes other sectors, such as land use or adaptation. It classifies COVID-19-related funding according to energy type, and it uses three buckets:

policy that supports the fossil fuel economy

policy that supports clean energy

and policy that supports other energy, such as nuclear and biofuels.

The overall balance for Aotearoa New Zealand was 44.6% fossil fuel-related, 54.5% clean energy, and less than 1% other energy. By global standards, that is a fairly middling performance.

Energy Policy Tracker, CC BY-ND

Among the countries the Energy Policy Tracker has analysed, the global average sees nearly one-half of economic stimulus going to fossil fuels, over one-third to clean energy, and one-sixth to other energy.

New Zealand’s performance looks increasingly ambivalent when we drop down to the next level of analysis.

Read more:

Rich and poor don't recover equally from epidemics. Rebuilding fairly will be a global challenge

The Energy Policy Tracker also analyses the environmental conditions placed on energy policy. On the one hand, it asks whether clean-energy policy involves major environmental trade-offs, such as fuel mixes that include oil or gas, or large hydropower projects that create emissions through construction and ecological disruption.

On the other hand, it asks whether fossil fuel-related policy comes with “green strings attached” that steer recipients toward cleaner long-term outcomes.

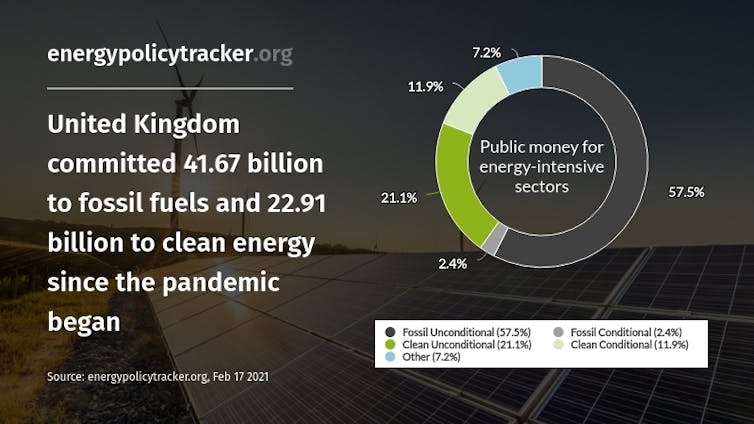

One example is the French government’s rescue package for Air France, which involved €7 billion in loans. It also requires Air France to renew its fleet with more fuel-efficient planes to reduce emissions, and to cease a few domestic routes that have transport alternatives like rail. Through policy innovations like this, about two-thirds of France’s fossil fuel-related stimulus is conditional.

Energy Policy Tracker, CC BY-ND

Among the countries the Energy Policy Tracker has analysed, the global average sees nearly one-half of economic stimulus going to fossil fuels, over one-third to clean energy, and one-sixth to other energy.

New Zealand’s performance looks increasingly ambivalent when we drop down to the next level of analysis.

Read more:

Rich and poor don't recover equally from epidemics. Rebuilding fairly will be a global challenge

The Energy Policy Tracker also analyses the environmental conditions placed on energy policy. On the one hand, it asks whether clean-energy policy involves major environmental trade-offs, such as fuel mixes that include oil or gas, or large hydropower projects that create emissions through construction and ecological disruption.

On the other hand, it asks whether fossil fuel-related policy comes with “green strings attached” that steer recipients toward cleaner long-term outcomes.

One example is the French government’s rescue package for Air France, which involved €7 billion in loans. It also requires Air France to renew its fleet with more fuel-efficient planes to reduce emissions, and to cease a few domestic routes that have transport alternatives like rail. Through policy innovations like this, about two-thirds of France’s fossil fuel-related stimulus is conditional.

Air France is expected to stop routes where low-emission transport alternatives exist.

Shutterstock/SAHACHATZ

Contrast this with New Zealand where one-twelfth of fossil fuel-related spending is conditional, such as road upgrades that incorporate cycling and pedestrian infrastructure. Meanwhile, 12 times as much, more than $1.4 billion, supports fossil fuel infrastructure unconditionally, much of it committed to Air New Zealand’s $900 million standby loan facility.

This is a lost opportunity to lock in the transition to a low-emissions economy.

Read more:

New Zealand's COVID-19 budget delivers on one crisis, but largely leaves climate change for another day

This is also mirrored on the other side of the ledger. Nearly $2 billion was spent on clean energy, but only one-quarter of this was unconditional. Big ticket items like wind farms are absent.

The majority went to clean conditional spending, such as investment in rail, ferry and bus infrastructure. Although these forms of public transport are more energy efficient, if they rely on fossil fuels they also emit carbon dioxide.

Compare that with the UK where relative support for unconditional clean energy policy was twice as high, including big commitments to energy efficiency, and walking and cycling infrastructure.

Air France is expected to stop routes where low-emission transport alternatives exist.

Shutterstock/SAHACHATZ

Contrast this with New Zealand where one-twelfth of fossil fuel-related spending is conditional, such as road upgrades that incorporate cycling and pedestrian infrastructure. Meanwhile, 12 times as much, more than $1.4 billion, supports fossil fuel infrastructure unconditionally, much of it committed to Air New Zealand’s $900 million standby loan facility.

This is a lost opportunity to lock in the transition to a low-emissions economy.

Read more:

New Zealand's COVID-19 budget delivers on one crisis, but largely leaves climate change for another day

This is also mirrored on the other side of the ledger. Nearly $2 billion was spent on clean energy, but only one-quarter of this was unconditional. Big ticket items like wind farms are absent.

The majority went to clean conditional spending, such as investment in rail, ferry and bus infrastructure. Although these forms of public transport are more energy efficient, if they rely on fossil fuels they also emit carbon dioxide.

Compare that with the UK where relative support for unconditional clean energy policy was twice as high, including big commitments to energy efficiency, and walking and cycling infrastructure.

Energy Policy Tracker, CC BY-ND

Takeaways for the next crisis

Given New Zealand will face further shocks in future, what lessons should we learn to improve our response?

Firstly, New Zealand is missing a trick on policy innovation. Some other countries are doing better, even in the midst of an emergency, to take an integrated approach that aligns crisis measures with long-term objectives.

Policy makers should be less reactive and more anticipatory. They should be working to create a climate-aligned investment pipeline, which is unambiguously weighted toward clean energy, with “green strings attached” wherever appropriate.

Secondly, the government should adopt a responsible investment framework, which prioritises low-emissions projects and screens out climate-misaligned investments.

In an emergency, decision making is often suboptimal because there is little time for due diligence. Some “shovel-ready” infrastructure projects ought to have been excluded on climate change grounds, including the Muggeridge Pump Station.

Thirdly, there is cause to be positive about New Zealand’s overall direction. Our strong baseline of renewable electricity means that untargeted economic stimulus is soaked up by a relatively clean energy system. Also, there are substantial commitments to non-energy climate policy, most notably the $1.245 billion Jobs for Nature programme.

The rudiments of a project pipeline have emerged through initiatives like the Provincial Growth Fund and various energy-related strategies, which were accelerated when the pandemic struck.

Consider, for example, the $18 million commitment to the Whale Trail, a 194km cycling and walking trail from Picton to Kaikōura, which enables travellers to explore their own backyard by climate-friendly means. If this is what climate-aligned infrastructure looks like, it is an investment we’re unlikely to regret.

Energy Policy Tracker, CC BY-ND

Takeaways for the next crisis

Given New Zealand will face further shocks in future, what lessons should we learn to improve our response?

Firstly, New Zealand is missing a trick on policy innovation. Some other countries are doing better, even in the midst of an emergency, to take an integrated approach that aligns crisis measures with long-term objectives.

Policy makers should be less reactive and more anticipatory. They should be working to create a climate-aligned investment pipeline, which is unambiguously weighted toward clean energy, with “green strings attached” wherever appropriate.

Secondly, the government should adopt a responsible investment framework, which prioritises low-emissions projects and screens out climate-misaligned investments.

In an emergency, decision making is often suboptimal because there is little time for due diligence. Some “shovel-ready” infrastructure projects ought to have been excluded on climate change grounds, including the Muggeridge Pump Station.

Thirdly, there is cause to be positive about New Zealand’s overall direction. Our strong baseline of renewable electricity means that untargeted economic stimulus is soaked up by a relatively clean energy system. Also, there are substantial commitments to non-energy climate policy, most notably the $1.245 billion Jobs for Nature programme.

The rudiments of a project pipeline have emerged through initiatives like the Provincial Growth Fund and various energy-related strategies, which were accelerated when the pandemic struck.

Consider, for example, the $18 million commitment to the Whale Trail, a 194km cycling and walking trail from Picton to Kaikōura, which enables travellers to explore their own backyard by climate-friendly means. If this is what climate-aligned infrastructure looks like, it is an investment we’re unlikely to regret.

Authors: David Hall, Senior Researcher in Politics, Auckland University of Technology