COVID hit casual academics hard. Here are 5 ways to produce a better deal for unis and staff

- Written by Elizabeth Baré, Honorary Fellow, LH Martin Institute, The University of Melbourne

Australian universities roughly doubled the number of casual staff employed to 23,000 (in full-time equivalents) from 2001 to 2019 (the latest year for which figures are available).

The greatest increase in casual staff has been in the academic workforce. The proportion of casual staff increased from 20% to 24% of this workforce in full-time equivalent (FTE) terms — as casual staff usually work part-time, we estimate that’s about 90,000 people.

Earlier this month, Universities Australia announced 17,300 university jobs had been lost due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It said the sector was likely to lose about A$3.8 billion in revenue in 2020 and 2021.

Based on previous analysis of individual university announcements in 2020 of job losses totalling around 6,000 FTE, it is highly likely most of the 17,300 jobs lost are people on casual or fixed-term contracts. A modest 10% reduction in academic casual staff would mean 9,000 lost their jobs. This has a significant impact on the capacity to teach domestic students.

There have been and will continue to be legitimate reasons for casual academic employment in higher education. A number of factors have prompted this steady increase in casualisation of academic work.

Two main considerations have been:

rapid growth in student numbers coupled with the decline in the real rate of government funding for teaching and research, making universities less keen to take on more “permanent” academic staff

very generous conditions attached to continuing employment, including 17% employer-provided superannuation, redundancy provisions well above community norms, highly regulated workload provisions and, for some, access to generous “outside work” entitlements.

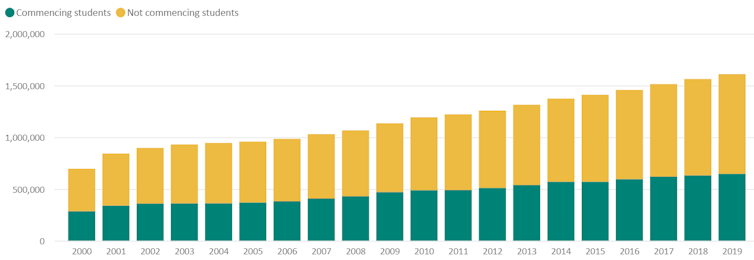

Total Australian university enrolments from 2000 to 2019.

Commonwealth Department of Education Skills and Employment, Selected Higher Education Statistics, CC BY

Total Australian university enrolments from 2000 to 2019.

Commonwealth Department of Education Skills and Employment, Selected Higher Education Statistics, CC BY

Relying too heavily on casual academic employment could be detrimental in the long term for the student experience, research programs and universities — as well as for the staff themselves.

In 2020, Australian universities responded quickly and nimbly to the immediate emergency created by COVID-19. In 2021, as a fresh round of enterprise bargaining begins, universities have an opportunity to capture the disruption created by the pandemic and reform the terms and conditions for their increasingly contingent and casualised academic workforce.

Here are five proposals that are readily achievable. Each would give better effect to universities’ stated commitments to value staff and allow them to fulfil their potential.

1. Allow fixed-term engagement for teaching duties

The Higher Education Industry (Academic Staff) Award specifically excludes the use of fixed-term contracts for staff whose main role is teaching. This provision can in turn be linked to the increasing use of casual staff for teaching. It limits the capacity of universities to take on new teaching staff in times of uncertain student demand.

Varying the award to allow universities to engage fixed-term staff for teaching duties would provide greater certainty for staff and a more consistent experience for students.

2. Change employment structures for teachers regularly employed as casuals

Limitations on fixed-term employment for teaching have resulted in expanded numbers of casual teachers. However, simply removing the restraint is unlikely to change employment patterns, as casual teaching tends to be concentrated in particular periods of the year.

A fixed-term contract that allows for engagement and payment across a year but with work more concentrated in specific periods will not only improve security of tenure, but also enable staff to undertake a broader range of tasks, including student consultation. It will also give these staff access to personal and professional benefits such as academic promotion.

A fixed-term contract that allows for engagement and payment across a year would enable staff to undertake a broader range of tasks such as student consultation.

Shutterstock

A fixed-term contract that allows for engagement and payment across a year would enable staff to undertake a broader range of tasks such as student consultation.

Shutterstock

3. Shift the casual pay structure from the 1980s to the 2020s

The current structure is based on the requirement to deliver hour-long lectures and tutorials and separate hourly rates for other academic duties such as marking, music accompaniment and nursing clinical supervision. All hourly rates attract a 25% loading to compensate for loss of annual and sick leave.

The Academic Salaries Tribunal (AST) codified the structure in 1980. The evolution of teaching since then means this structure no longer reflects the breadth of work required. These changes include:

team teaching (staff collaborate on delivery)

the flipped classroom model (students absorb the lecture and reading materials online at home, then discuss this or work on live problem-solving in classes)

the use of workshops and other hands-on work

online teaching where staff must be responsive to student work.

4. Create a reward/career structure for casual teaching staff

Many of these staff are both expert in their field and excellent teachers. They include industry professionals and practitioners.

Some universities have developed promotion systems for honorary staff, especially where an academic title is important to professional standing. These processes might be adapted for casual teachers. They could then be appointed or promoted to an academic rank based on merit and receive pay to match, albeit as a casual employee.

5. Allow for core entitlements to be portable

The careers of many academic staff are now built on concurrent or consecutive appointments at several universities. Universities generally have provisions for recognising prior service at another university, but these largely benefit continuing staff.

The creation of the higher education industry superannuation scheme, UniSuper, in 1983 is an example of a whole-of-sector collaboration that has benefited staff and universities. A similar cross-sector framework to recognise service at another university should be considered. This might extend to the training and accreditation of casual teachers, ensuring quality across the sector. And in the case of fixed-term staff, it might allow for core entitlements such as annual and sick leave to be more portable.

The pandemic has greatly sharpened Australian universities’ focus on their staff and HR policies, structures and strategies. This presents an opportunity to review and greatly improve the employment practices for casual academic staff, in particular those relating to core student teaching.

The detailed analysis on which this article is based can be found here.

Authors: Elizabeth Baré, Honorary Fellow, LH Martin Institute, The University of Melbourne