Film review: Wild Things packs passionate climate activism into an overly polite documentary

- Written by Ari Mattes, Lecturer in Communications and Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

The content of some films is so close to the heart that it’s difficult to critically evaluate them. If you’re an atheist, The Passion of the Christ is not for you. By the same token, if you’re a denier of anthropogenic global warming, then you’ll hate Wild Things, the latest film from Australian producer-director Sally Ingleton.

A passionate call to action against global warming, Wild Things is documentary at its slickest, even if it is oddly-named (sharing the title with the 1998 risque romp Wild Things).

It seamlessly combines archival footage, camera phone footage, stunningly panoramic aerial photography and beautiful-in-forest images with the whole thing anchored around a group of very likeable environmental activists.

To every season, turn

In keeping with the subtitle — A Year on the Frontline of Environmental Activism — Wild Things follows a group of activists (it’s not clear why they are called “wild things” or by whom) – with each section of the film following a season.

We move from the anti-Adani campaign in Central Queensland led by Andy Paine at Camp Binbee, to Lisa Searle and the campaign to save old-growth forests in Tasmania, to high school students Milou Albrecht and Harriet O’Shea Carre from Castlemaine in regional Victoria as they found their own climate change movement.

Dr Lisa Searle climbing an old growth tree she is fighting to protect.

Tim Cooper/Potential Films

Dr Lisa Searle climbing an old growth tree she is fighting to protect.

Tim Cooper/Potential Films

The groups often face serious peril — we see a semi-trailer pushing against protesters outside an Adani contractor site — yet continue their passionate fight for ecological justice.

In many respects, this is an optimistic film. We can feel the enthusiasm of Albrecht, and O’Shea Carre as their campaign spreads from 20 to thousands of students. We even travel to New York City with the latter as she watches, starstruck, as her idol Greta Thunberg addresses a rally.

In other ways, the film is deeply sad. We are forced to witness the brutal destruction of Tasmanian forests.

Read more: Friday essay: why we need children's life stories like I Am Greta

Across time and place

The old cliche of the dole-bludging treehugger is quickly dispensed with. We follow an organised group of people as they brush up against the systems that began and perpetuate anthropogenic global warming. There isn’t much of a focus on their powerful antagonists, but, one senses, they probably don’t need more opportunities in the spotlight.

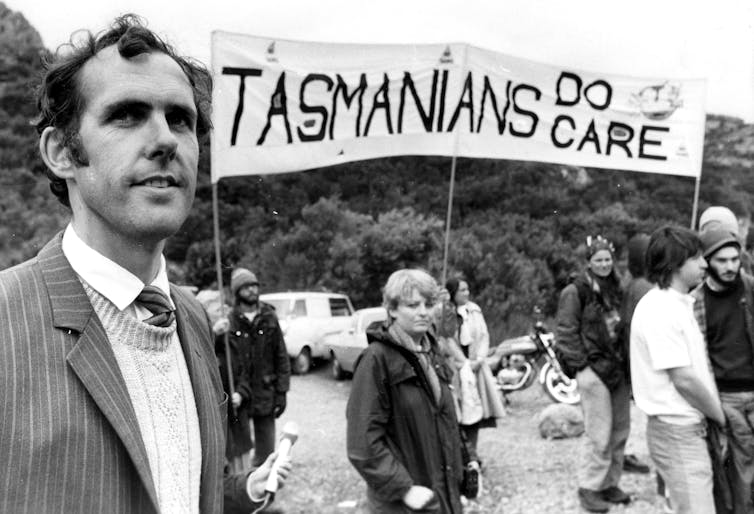

We also see the activists’ canny use of social media and new technologies to generate support. As the film points out, these are radically different times from those of the Franklin River Dam protest, when film had to be flown in and out every day.

The film includes a look at historical events, like a rally at Tasmania’s Crotty Road in 1983.

Potential FIlms

The film includes a look at historical events, like a rally at Tasmania’s Crotty Road in 1983.

Potential FIlms

Specific campaigns are put in the broader context. The film’s style — its balance between types of footage, and across geographical and temporal locations — seems to embody an ecological rationale. Every part (past or present, here or there) is connected to every other part.

And so notable past Australian environmental campaigns are interspersed with coverage of the current year. The Green Bans in Sydney’s Rocks in the 1970s, Bob Brown and the Franklin River Dam protests in the 1970s and 1980s, and the anti-Jabiluka mine protest of 1998 all make an appearance. Some of this involves contemporary interviews with major players, but much of it is meticulously put together from archival footage.

This temporal cross section seems as significant as the geo-spatial one, and this appears to be a key point the film would like to make. Global warming and ecology are about time — like all death, about temporal limitation.

The continuity of these struggles past and present is of prime significance — the victories as well as the defeats.

Read more: Ignoring young people's climate change fears is a recipe for anxiety

Passive protest

Wild Things may have been conceptually stronger — and more critically coherent — if this point had been made in a more forceful and direct fashion.

Perhaps this is part of its vision — things aren’t neat in this space. Or maybe it’s symptomatic of a more significant criticism: the whole thing seems a little too polite.

Harriet O'Shea Carre and Milou Albrecht founded their own climate change movement in Castlemaine.

Julian Meehan/Potential Films

Harriet O'Shea Carre and Milou Albrecht founded their own climate change movement in Castlemaine.

Julian Meehan/Potential Films

Wild Things is a document of people struggling to save the planet — and this is as brutal and existentially charged a battle as you can get, lebensraum (the German concept of “living space” for humans) for the population of the entire globe.

Yet interviewees repeatedly emphasise they are “non-violent” as though constantly apologising, in advance, to some imagined criticism.

This disclaimer appears frequently towards the beginning of the film, as though thereby allowing it entry into polite discourse. At times the film seems similarly gentle, genteel — even middlebrow — in its approach to global warming.

It is most impressive as a piece of documentary cinema. Its production value is exceptional, and the balance, in terms of style of footage, is excellent. Fly-on-the-wall footage unfolds amid carefully placed interviews and video diaries. The 90-minutes duration passes in a flash.

The score is a little uninspired but also doesn’t distract from the content of the film. A documentary of this scale is not going to be able to afford composer John Williams — but Missy Higgins sings the closing number, The Difference.

Wild Things is definitely not a non-partisan film — but why should it be? It’s on the side of the population of the globe!

Still, a more detailed and engaged analysis of the relationship between past and present would have enriched its ultimate call to action. It is good — it’s emotionally compelling and enjoyable — but one can’t help feeling a more intellectually robust and less sentimental approach may have made it great.

Read more: How the youth climate movement is influencing the green recovery from COVID-19

Wild Things is in cinemas from today.

Authors: Ari Mattes, Lecturer in Communications and Media, University of Notre Dame Australia