'Wild enchantment': how Daniel Thomas's writings conveyed the joy of art to Australians

- Written by Joanna Mendelssohn, Principal Fellow (Hon), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, University of Melbourne

Review: Daniel Thomas, recent past: writing Australian art, edited by Hannah Fink and Stephen Miller (Thames & Hudson Australia)

In 1958, when the young Daniel Thomas was first appointed at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the word “curator” was not in the Public Service Board lexicon. He felt his official title of “professional assistant” was inaccurate so he signed his letters “curatorial assistant”.

In time, the bureaucracy adopted his language and the term is still used to describe the entry level curatorial position for new graduates.

The years I spent working for Thomas as a curatorial assistant in the 1970s transformed my understanding of what art can do. His generous pedantry means that even now I sometimes hear his voice in my ear, questioning the precise meaning of a word I want to use.

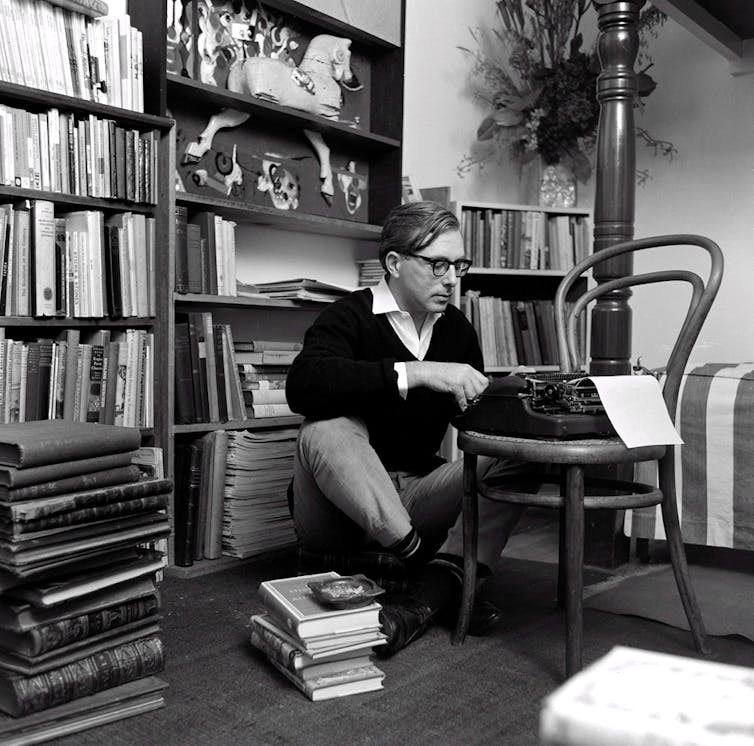

Robert Walker,

Daniel Thomas in his apartment at Elizabeth.

Bay, from the Robert Walker archive 1965

black and white negative, 6 x 6 cm

National Art Archive|, Art Gallery of New South

Wales

© Estate of Robert Walker

Robert Walker,

Daniel Thomas in his apartment at Elizabeth.

Bay, from the Robert Walker archive 1965

black and white negative, 6 x 6 cm

National Art Archive|, Art Gallery of New South

Wales

© Estate of Robert Walker

Thomas has been such a force for change in Australian art that he has influenced almost every institution, curator and artist.

Read more: Beauty and audacity: Know My Name presents a new, female story of Australian art

He was, in turn, the first curator at the AGNSW, the inaugural Head of Australian art at the National Gallery of Australia and Director of the Art Gallery of South Australia, before retiring to Tasmania, close to where he was born 89 years ago. Here he continues to write and mentor those who wish to know both the small details and large visions of art in Australia.

In the 1960s and 70s, however, Thomas was perhaps better known as the witty and informative art critic of first the Sunday Telegraph and later the Sydney Morning Herald. His initial appointment, which today would be regarded as a conflict of interest, was seen at the time as a way of educating the public about the importance of art.

He also wrote perceptive extended essays for Art and Australia and later Art Monthly, as well as essays in scholarly catalogues. Steven Miller and Hannah Fink’s anthology, Recent Past: writing Australian art, has managed the Herculean task of condensing the essence of Thomas’s writing into one enjoyable volume, a scholarly resource that also delights the general reader.

Thomas has little time for theoretical constructs. Instead he focuses on art, artists and circumstance. “Fieldwork is more fun than library research,” he writes as he discusses both the landscape where John Glover painted and the mirrored wardrobe, which was the subject of many of Grace Cossington Smith’s late, great paintings.

Read more: How our art museums finally opened their eyes to Australian women artists

A brief to educate

Some scholars hug their knowledge to themselves, content to communicate only with their peers. Thomas sees his mission to spread the word, to let as many people as possible know the profound joy of art.

He soon became the master of the deft phrase. John Brack is described as “a clever painter, clever to the point of teasing”. Fred Williams’ paintings are “invested with magic”. An early painting by Janet Dawson is described with gusto as “an exhilarating event”. In later critiques he notes with pleasure Rosalie Gascoigne’s “well-made things” and describes Dorrit Black as one of “the reserved but passionate temperaments” in her art.

Read more: Fred Williams in the You Yangs: a turning point for Australian art

In this new book, Thomas has provided a written commentary on both his past writing and the illustrations. These intriguing, informative and often humorous notes are marked as “DT20”.

Martin Sharp.

Miss Australia 1975

synthetic polymer paint on hardboard, 181.7 x 147.3 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales

© Estate of Martin Sharp

Martin Sharp.

Miss Australia 1975

synthetic polymer paint on hardboard, 181.7 x 147.3 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales

© Estate of Martin Sharp

In a note on Martin Sharp’s Miss Australia, for instance, he writes that the artist “emphasised it was painted entirely by him”. Then, almost as an aside, Thomas tells the reader Sharp did not physically paint some works attributed to him, but rather delegated the hard slog to his studio assistant, Tim Lewis.

Obituaries written for artists are written with an eye to the longer judgement of history. In his considered obituary for Arthur Boyd, Thomas concludes “an uneven painter must be judged on his best works”, a subtle reminder that Boyd made many potboilers.

Pop artist Robert Rooney, he wrote, “failed a Swinburne Technical College commercial-art-diploma course in illustration and design but did not waste the experience.”

‘More exciting museums’

As the articles are arranged in chronological order it is possible to track how Thomas has long used his privileged background for good.

His “first schoolboy glimpse of the wild enchantment of art” came when he was a student at Geelong Grammar, inspired by the Bauhaus refugee artist Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack. An Oxford degree and a deep knowledge of European art could have led to a career in the UK, but he chose to work in Australia as, “I wanted our art museums to be more exciting.”

Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack.

The world to come 1940

pencil, watercolour on ivory wove paper,

varnish, 17.7 x 24.8 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales

© Estate of Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack

Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack.

The world to come 1940

pencil, watercolour on ivory wove paper,

varnish, 17.7 x 24.8 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales

© Estate of Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack

The penultimate essay, Spirit of Place, written in 2018, can be described as a meditation on rock, trees, life and art. Thomas considers how the land he has known since childhood has changed “under unkind management by thoughtless humans”. Plastic is washed on the Bass Strait seashore when once it was kelp.

He has named his house, Loeyunnila, the word Aboriginal people from Port Sorrell use for “high wind”. But he remembers, too, how Aboriginal people from this place were taken by boat in “an exile equivalent to a death sentence”.

There is a tension between his appreciation of enduring Aboriginal cultures and knowledge that it was his direct ancestors who dispossessed them of their land. He resolves this by suggesting that “Aboriginal people are re-conquering the minds of their invaders, just as the Greeks re-conquered the ancient Romans.”

As with much of Thomas’s writing, it is an idea worth debating.

Authors: Joanna Mendelssohn, Principal Fellow (Hon), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, University of Melbourne