Jane Austen, Monet and Phantom of the Opera – middlebrow culture today

- Written by David Carter, Professor emeritus, The University of Queensland

Culture has long been stratified as “high” or “low”, or perhaps “high” and “popular” to soften the blow. But what about the in-between?

The word “middlebrow” emerged into English in the 1920s as an insult. It described works that mistook mere good taste for serious art - and consumers who couldn’t tell the difference.

We asked almost 1500 Australians about their cultural preferences and participation, and mapped their responses on a spectrum. There is a clear divide between those who don’t regularly engage with arts and culture on one side and the dedicated lovers of high or avant-garde art forms on the other.

The most concentrated area of mapped data was in the middle space. This patch – filled with likes for Phantom of the Opera, Rhapsody in Blue, light classical music and jazz, TV documentaries and police shows, Monet and Ken Done, Tim Winton, Jane Austen and more – can tell us what constitutes middlebrow culture today.

Read more: Australians' favourites show Aboriginal art can transcend social divisions and art boundaries

Airs and graces

From the early decades of the 20th century, the new twin forces of modernist high culture and mass commercial culture produced ongoing fights over cultural value and authority among critics and consumers alike in a “battle of the brows”.

The language of brows suggested not just different but dramatically opposed tastes. Worse, the three brow levels could be taken to represent high, low and middle-class tastes. Any rise from below threatened those above.

Most threatening to cultural elites was not the vulgar but the middlebrow’s pretensions to culture and good taste. As Virginia Woolf put it, the middlebrow was:

… of middlebred intelligence … in pursuit of no single object, neither art itself nor life itself, but both mixed indistinguishably, and rather nastily, with money, fame, power, or prestige.

Middlebrow art imitated serious art, but only offered easy pleasure. Middlebrow consumers aspired to culture, but for its social prestige. Middlebrow institutions like book clubs or radio made high culture accessible to all, supposedly “dumbing it down” in the process.

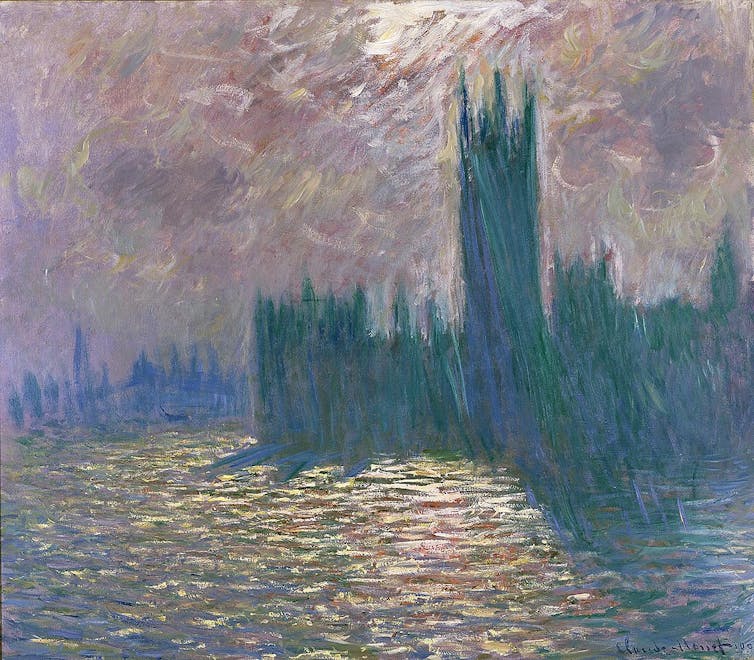

London, Parliament, Reflections on the Thames by Claude Monet (1905).

Wikimedia Commons

London, Parliament, Reflections on the Thames by Claude Monet (1905).

Wikimedia Commons

Read more: Friday essay: the politics of dancing and thinking about cultural values beyond dollars

Major works, minor arts

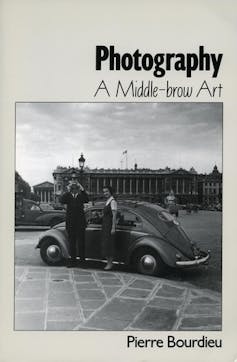

For French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, “middle culture” comprised the “major works of the minor arts” and the “minor works of the major arts”. But almost anything could be deemed middlebrow depending on how it was perceived or packaged.

There’s nothing essentially middlebrow about Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, landscape painting or Jane Austen’s novels, but the term could describe most occasions for their consumption today – Vivaldi over dinner, landscapes in the gallery gift shop, Austen in The Jane Austen Book Club!

The works still carry their prestige as serious art, but packaged for pleasurable or tasteful consumption.

Since the 1990s a new field of middlebrow studies has arisen, relocating the middlebrow in cultural history to understand it in its own right. Scholars have identified recurrent aspects of middlebrow culture: taking culture seriously as “purposeful recreation” or empathetic engagement but also as a source of pleasure; open to both high and popular culture but within clear boundaries, nothing too arty or abstruse, nothing trashy or cheap.

Goodreads

The Australian Cultural Fields project conducted a national survey of Australians’ cultural preferences in 2015, and in the new book, Fields, Capitals, Habitus: Australian Culture, Social Divisions and Inequalities, specific attention is given to the “middle space” of Australian cultural tastes and engagement.

A map of the middle

Individuals’ likes and dislikes for certain kinds of books, art, music, TV, heritage and sport, and participation in cultural activities, were mapped so that shared preferences would be clustered together. So too attitudes to certain named artists, authors, composers, and TV and sports personalities. These results were mapped against social variables including age, gender, education and occupational class.

This exercise revealed two very different zones of taste and engagement, and a crowded middle space between.

On one side is a zone of low participation (42% of those surveyed) where negative responses are registered for almost all book types, for Impressionism, Renaissance and abstract art, classical and light classical music, TV arts and documentary programs, and more.

Likes and engagement are restricted to commercial TV, reality and sports shows, country music, landscapes and portraits, sports books, author Stephen King, family and homeland heritage, and rugby league.

On the other side (21%), positive tastes are dominant, especially for the traditionally prestigious or “learned” items such as literary classics, modern novels, Impressionism, Indigenous books, Aboriginal and migrant heritage, the ABC and SBS, author David Malouf and artist Margaret Preston. Dislikes register for certain popular or declassé genres including dance music and landscapes.

But the densest concentration of likes and dislikes falls in the cultural middle ground. This helps us visualise the middlebrow. Positive responses congregate around classical music, Aboriginal and Renaissance art, Australian histories and biographies, crime novels, TV news and lifestyle programs.

Goodreads

The Australian Cultural Fields project conducted a national survey of Australians’ cultural preferences in 2015, and in the new book, Fields, Capitals, Habitus: Australian Culture, Social Divisions and Inequalities, specific attention is given to the “middle space” of Australian cultural tastes and engagement.

A map of the middle

Individuals’ likes and dislikes for certain kinds of books, art, music, TV, heritage and sport, and participation in cultural activities, were mapped so that shared preferences would be clustered together. So too attitudes to certain named artists, authors, composers, and TV and sports personalities. These results were mapped against social variables including age, gender, education and occupational class.

This exercise revealed two very different zones of taste and engagement, and a crowded middle space between.

On one side is a zone of low participation (42% of those surveyed) where negative responses are registered for almost all book types, for Impressionism, Renaissance and abstract art, classical and light classical music, TV arts and documentary programs, and more.

Likes and engagement are restricted to commercial TV, reality and sports shows, country music, landscapes and portraits, sports books, author Stephen King, family and homeland heritage, and rugby league.

On the other side (21%), positive tastes are dominant, especially for the traditionally prestigious or “learned” items such as literary classics, modern novels, Impressionism, Indigenous books, Aboriginal and migrant heritage, the ABC and SBS, author David Malouf and artist Margaret Preston. Dislikes register for certain popular or declassé genres including dance music and landscapes.

But the densest concentration of likes and dislikes falls in the cultural middle ground. This helps us visualise the middlebrow. Positive responses congregate around classical music, Aboriginal and Renaissance art, Australian histories and biographies, crime novels, TV news and lifestyle programs.

Me? Middlebrow? Jane Austen’s works, including Pride & Prejudice, sit proudly at the centre.

IMDB

In terms of named artists and works, the middle space is even more crowded. In the literary field, Jane Austen sits proudly at the centre, alongside authors such as Bryce Courtenay, Jodi Picoult and Woolf, and painters Rembrandt, Monet and Jackson Pollock. Musically, Nessun Dorma and Phantom of the Opera are playing.

Dislikes also fall within the middle space: for Ben Quilty, Francis Bacon, Kate Grenville, Ian Rankin, Ai Weiwei and Caravaggio (alongside Stephen King, Big Brother and Kylie Minogue!). The very presence of the negative responses, however, suggests cultural capital – that it matters to have a view on such figures, even if negative.

Read more:

Artists help communities during a crisis, not hinder. Why are we still told they don't matter?

Who likes the middle?

We can map the distribution of tastes against key social variables. The middle space corresponds closely to lower professional-managerial occupations (like teachers, curators, academics); tertiary (but not postgraduate) education; the 45-64 age group; and urban or suburban residents. Women occupy the middle space; men are closer to the less engaged zones. There is no simple alignment with class; middlebrow culture doesn’t align neatly with the “middle class”.

The term “middlebrow” remains difficult because of its still potent, pejorative connotations. What it can tell us is that imagining culture divided simply into high and low won’t get us very far. There is plenty to enjoy in the middle space.

Me? Middlebrow? Jane Austen’s works, including Pride & Prejudice, sit proudly at the centre.

IMDB

In terms of named artists and works, the middle space is even more crowded. In the literary field, Jane Austen sits proudly at the centre, alongside authors such as Bryce Courtenay, Jodi Picoult and Woolf, and painters Rembrandt, Monet and Jackson Pollock. Musically, Nessun Dorma and Phantom of the Opera are playing.

Dislikes also fall within the middle space: for Ben Quilty, Francis Bacon, Kate Grenville, Ian Rankin, Ai Weiwei and Caravaggio (alongside Stephen King, Big Brother and Kylie Minogue!). The very presence of the negative responses, however, suggests cultural capital – that it matters to have a view on such figures, even if negative.

Read more:

Artists help communities during a crisis, not hinder. Why are we still told they don't matter?

Who likes the middle?

We can map the distribution of tastes against key social variables. The middle space corresponds closely to lower professional-managerial occupations (like teachers, curators, academics); tertiary (but not postgraduate) education; the 45-64 age group; and urban or suburban residents. Women occupy the middle space; men are closer to the less engaged zones. There is no simple alignment with class; middlebrow culture doesn’t align neatly with the “middle class”.

The term “middlebrow” remains difficult because of its still potent, pejorative connotations. What it can tell us is that imagining culture divided simply into high and low won’t get us very far. There is plenty to enjoy in the middle space.

Authors: David Carter, Professor emeritus, The University of Queensland