Freeman review: documentary relives the time Cathy Freeman flew, carrying the weight of the nation

- Written by Heidi Norman, Professor, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney

Where were you when Catherine Freeman won gold at the Sydney Olympic Games?

Director Laurence Billiet draws the memories of the nation together with sound and vision from the televised records, around Freeman’s own generous, lilting telling of this story.

In Freeman, Billiet returns us to the drama and theatre of the “moon that rises every four years”, the peak of every athlete’s dream, the greatest show on earth — the Olympic Games.

Two dramatic narratives arc through this documentary, which marks 20 years since the triumph: Freeman’s personal reflections as an elite athlete, and our experience as a nation of spectators.

Timing the run

By September 2000 — the year of the Sydney Olympic Games — Cathy Freeman had risen to be the 400 metres female world champion. For a country without a strong track and field history, the hosting of the Olympics on Freeman’s home soil aligned perfectly with her career peak and the wane of her role model and rival, Marie-José Pérec.

For a nation of thousands of generations, the last several in the company of outsiders, 49.11 seconds (Freeman’s time in the Olympic final) crystallised the hopes, dreams and heart of the combined citizenry for a future that embraced First Peoples.

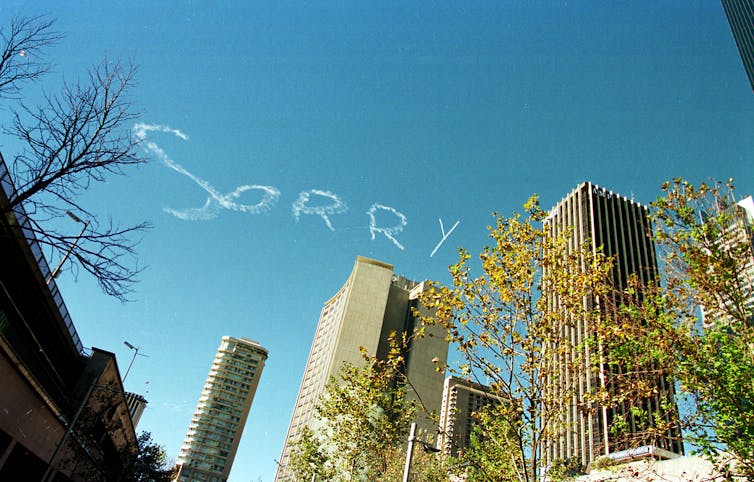

Just months prior, hundreds of thousands of Australians made public show of our desire for a more reconciled nation. In late May 2000, a seemingly endless stream of men, women and children adorned in red, black and yellow surged into a bitterly cold Sydney winter’s day in splendid procession over the Harbour Bridge, under the word “Sorry” scrawled across the bright blue sky.

Freeman’s win came a few months after the Walk for Reconciliation inspired hope.

AAP/Dave Hunt

Freeman’s win came a few months after the Walk for Reconciliation inspired hope.

AAP/Dave Hunt

Reckoning with the past treatment of Indigenous peoples and our relational places in the present had been a decade’s work for the Reconciliation Council, culminating in those bridge walks in cities and towns across the nation. The removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children was in sharp focus: the political class refusal of the call for a national apology an enduring disappointment

Debates over the nation’s history came to be crudely represented in binary accounts of “white blindfold” versus “black arm band”.

For the artists curating the Olympics opening ceremony, the challenge of representing the newly appreciated antiquity, coloniality and modernity was at the cutting edge of reckoning with these debates. They projected to the world a successful — although fragile — ancient, settler and migrant great southern land.

In Freeman, Billiet collaborates with Bangarra Dance Theatre’s artistic director Stephen Page to weave this forward, punctuating the film with distillations of ceremonial sound and movement.

Read more: Sit on hands or take a stand: why athletes have always been political players

Charming and disarming

Amid highly contested debates and the uncomfortable (for some) reality of a white nation’s precarious assertions in an ancient landscape, rose a slightly built, gap-toothed, gifted and competitive Cathy Freeman. Immensely disarming and charming, graceful and gracious, she captivated the nation.

Freeman in peak form.

AAP/Dean Lewins

Freeman in peak form.

AAP/Dean Lewins

Billiet presents Freeman with floating projections that illustrate her memories. The collective experience is portrayed in sound clouds capturing journalists, politicians, agitators and community in chorus: “Cathy Freeman … Cathy Freeman …”, “we are …” we are …", “Wait a minute … she’s coming third …”.

These threads merge in the gut-wrenching moment when we wiped tears from our eyes, disentangled from shared embraces and came to realise the duality of that burden on Freeman. At just 1.63 metres tall she had just carried her own and the nation’s hopes and dreams over the finish line.

Talking us stride by stride through her race, she says she was in flight. With 80 metres to go Freeman says, “I felt protected”. Billiet switches sound from the roar of the crowd to women singing and a cloud of white ochre erupts to catalyse everything Freeman has expressed about her ancestral connections and our aspirations for nationhood.

What a champion. What a relief.Read more: Damien Hooper, the Aboriginal flag and the right to freedom of speech

Thrills and spills

Freeman offers jewels of insight to her athleticism, explaining running as her “first ever greatest love”; races like a “first kiss”. From the age of five, running was “like flying’, like a "slip stream that leads you straight into heaven”.

Competitors, coaches and commentators enthused over her “beautiful movement” and “flowing free style”; so smooth, so natural.

Freeman was undefeated in the four years leading up to the 2000 Olympic Games. Her nemesis and inspiration, the magnificent competitor Marie-José Pérec, occupied a critical role, which is captured in the film.

Returning from injury to compete in Sydney, Perec was confronted by intense media scrutiny. On her sudden departure from the Games without competing, Perec noted she was facing “not a race against Cathy Freeman, but a race against an entire nation”.

Freeman shares her disappointment she never had the chance to take on her rival, and that she could have run a sub 49 second time. But such was the tempo of the race, coupled with the sheer weight that she had borne for the nation since lighting the cauldron at the commencement of the Olympic Games. She was in constant company with “the beast” — as Freeman characterised the media scrum.

Freeman reflects on running, her first love.

Daniel Boud

Freeman reflects on running, her first love.

Daniel Boud

Read more: Why being a sporting role model isn't as simple as most people think

The other thrilling element of the documentary is the generous view granted into Freeman’s family life. She credits her sister Anne Marie, who lived until 1990 with cerebral palsy, for life lessons in humility and acceptance. Billiet honours the gentle strength of her mum, Cynthia, and motivating support from stepfather and earliest coach Bruce Barber, who she called “Blue Eyes”.

Of that Olympic moment, we gain profound insight into Freeman’s growing appreciation of her identity and conviction to be proud in a race that risked the nation’s heart. Robed in the Aboriginal and the Australian flag, Freeman found expression for herself, and for all of us.

To watch the film is to relive a moment when we held enormous optimism for our reconciled nation and of Freeman’s reckoning with her own identity: look at me; I’m black and I’m the best. No more shame.

FREEMAN screens on ABC television on Sunday, September 13 at 7.40pm and then on ABC iview.

Authors: Heidi Norman, Professor, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney