'Uprooting, no matter how small a plant you are, is a trauma': older women renters are struggling

- Written by Emma Power, Senior Research Fellow, Geography and Urban Studies, Western Sydney University

Older women renters are struggling in an insecure and unaffordable rental housing market. A combination of high rents and low incomes leaves many living in substandard housing and unable to afford necessities like food and energy bills.

My research shows rent increases further stress household budgets, and evictions magnify these risks. COVID-19 makes the need for reform even more urgent. Secure housing is the first line of community defence against the pandemic.

Read more: 400,000 women over 45 are at risk of homelessness in Australia

Unaffordable, substandard rentals

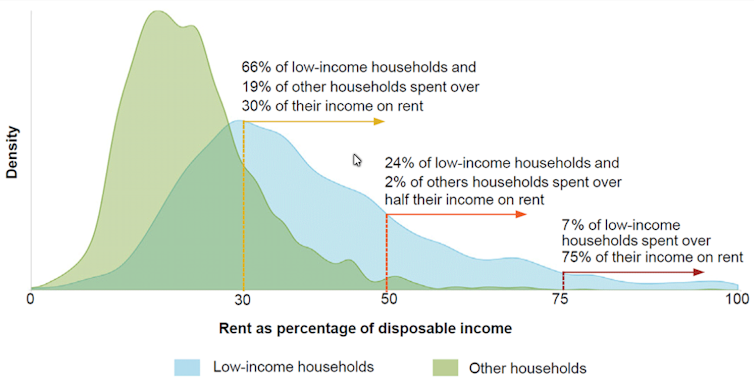

Rental stress occurs when households spend more than 30% of their income on rent. On average, low-income households spend “almost 40% of their disposable income on rent”.

Many households experience relatively short periods of rental stress. However, older low-income renters have very limited options.

In a report released today, single older women living on low incomes describe to me how high and rising rents left them struggling to meet day-to-day costs. Many paid rent before they bought food or paid power bills because the alternative was eviction. This is why the Productivity Commission describes rental affordability as a “driver of disadvantage” for low-income households.

Productivity Commission, CC BY

Read more:

Growing numbers of renters are trapped for years in homes they can't afford

For example, a rent increase left Tracey, a participant in my research, with only $30 after other essential costs were covered. She described her efforts to survive as “like my job. I’d go to one [charity] where they had the food cupboard and fresh produce” and to another where she could get a monthly food voucher. This experience was common.

To reduce their rental costs women often lived in substandard housing. For example, Michelle moved house seven times to find more affordable housing. She described her most recent house:

Gaps around all the windows and all the doors where literally, when it was windy, the curtain would blow and the wooden shutters, the wooden blinds, would actually blow.

While the rent was affordable, the cost for the house “rose astronomically” due to the need to use a heater throughout winter. Another participant, Toni, bought heavy curtains to try to block out the cold in her rental and, in an extreme example, clad the outside of two properties with tarpaulins to reduce draughts.

Rental insecurity

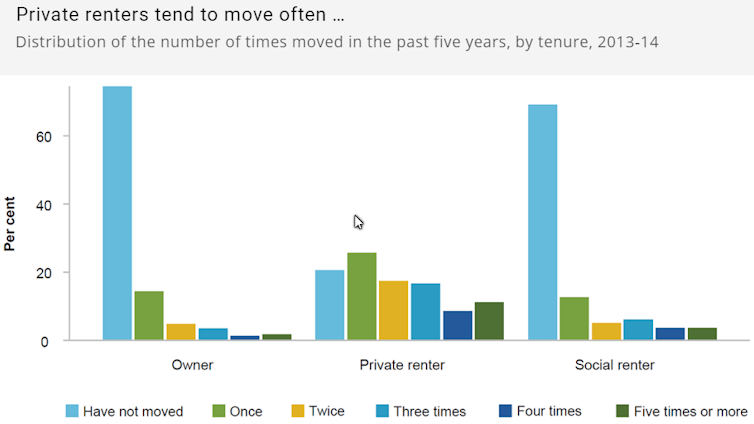

Older women also lived with high levels of rental insecurity. Private renters move more often than people in other housing tenures.

Productivity Commission, CC BY

Read more:

Growing numbers of renters are trapped for years in homes they can't afford

For example, a rent increase left Tracey, a participant in my research, with only $30 after other essential costs were covered. She described her efforts to survive as “like my job. I’d go to one [charity] where they had the food cupboard and fresh produce” and to another where she could get a monthly food voucher. This experience was common.

To reduce their rental costs women often lived in substandard housing. For example, Michelle moved house seven times to find more affordable housing. She described her most recent house:

Gaps around all the windows and all the doors where literally, when it was windy, the curtain would blow and the wooden shutters, the wooden blinds, would actually blow.

While the rent was affordable, the cost for the house “rose astronomically” due to the need to use a heater throughout winter. Another participant, Toni, bought heavy curtains to try to block out the cold in her rental and, in an extreme example, clad the outside of two properties with tarpaulins to reduce draughts.

Rental insecurity

Older women also lived with high levels of rental insecurity. Private renters move more often than people in other housing tenures.

Productivity Commission, CC BY

Most older Australians wish to age in place in a familiar home and community. This is not an option for many older renters.

Read more:

For Australians to have the choice of growing old at home, here is what needs to change

Older renters face a higher risk of eviction. Landlord decisions to repurpose housing or increase rents can trigger involuntary moves. These are recognised drivers of first-time homelessness in older age.

For low-income older renters moving house drives financial risks. Moving house can be expensive. Costs include bond (typically four weeks’ rent, paid in advance), disconnection and reconnection of utilities, and removalists or vehicle hire.

Productivity Commission, CC BY

Most older Australians wish to age in place in a familiar home and community. This is not an option for many older renters.

Read more:

For Australians to have the choice of growing old at home, here is what needs to change

Older renters face a higher risk of eviction. Landlord decisions to repurpose housing or increase rents can trigger involuntary moves. These are recognised drivers of first-time homelessness in older age.

For low-income older renters moving house drives financial risks. Moving house can be expensive. Costs include bond (typically four weeks’ rent, paid in advance), disconnection and reconnection of utilities, and removalists or vehicle hire.

The costs of moving house can set back renters’ budgets for months.

Shutterstock

As Gwen explained, “It’s all a cost factor.” For women living on already stretched budgets the risks are magnified.

Many women borrowed money to cover moving costs. This left them in debt that, as Gail explained, could take “months” to recover from.

Most downsized their possessions to make moving house cheaper and more manageable. Jenny explained:

You’ve got no choice. You’re parting with things that – well everything you’ve got together are part of your belongings and part of who you are and who you’ve established yourself to be. […] It’s part of your home.

Michelle drew parallels with the experiences of people “whose house caught fire or who’d had a flood” – only she was able to make choices about what to keep and what to give away.

The emotional costs were immense. Women described the stress and disappointment of forced relocations. Jenny explained the need to emotionally detach from her house:

And once you know you’re moving, all of a sudden that house is no longer your home. You get to the point of saying, okay, this house isn’t mine – it’s only a house where I’m living at the moment.

Relocating, Alice explained:

[…] means rifling through my paltry possessions fairly often and that I find upsets me a bit. […] uprooting, no matter how small a plant you are, is a trauma.

I report on these experiences of having to move house in further detail in a just-released research paper.

Read more:

What sort of housing do older Australians want and where do they want to live?

It is time for reform

Our federal government needs to permanently raise the JobSeeker payment and act on housing affordability to give low-income renters a fighting chance.

At a state level, it is time to end “no grounds” evictions. “With cause” measures, as recently introduced in Victoria, better balance tenants’ needs for housing security with the rights of landlords to repurpose properties when required.

We also need quantified minimum rental housing standards. New Zealand’s Healthy Homes standards can be a model for us. These standards ensure only properties that are healthy and sound go to market.

Read more:

Chilly house? Mouldy rooms? Here's how to improve low-income renters’ access to decent housing

The number of older Australians who rent is projected to increase over the next decade as home ownership levels decline. The stories of older women in the private rental sector are a warning about the risks that declining housing affordability and rental insecurity pose to this growing group. They are the “canary in the coalmine” for Australia’s housing system.

The costs of moving house can set back renters’ budgets for months.

Shutterstock

As Gwen explained, “It’s all a cost factor.” For women living on already stretched budgets the risks are magnified.

Many women borrowed money to cover moving costs. This left them in debt that, as Gail explained, could take “months” to recover from.

Most downsized their possessions to make moving house cheaper and more manageable. Jenny explained:

You’ve got no choice. You’re parting with things that – well everything you’ve got together are part of your belongings and part of who you are and who you’ve established yourself to be. […] It’s part of your home.

Michelle drew parallels with the experiences of people “whose house caught fire or who’d had a flood” – only she was able to make choices about what to keep and what to give away.

The emotional costs were immense. Women described the stress and disappointment of forced relocations. Jenny explained the need to emotionally detach from her house:

And once you know you’re moving, all of a sudden that house is no longer your home. You get to the point of saying, okay, this house isn’t mine – it’s only a house where I’m living at the moment.

Relocating, Alice explained:

[…] means rifling through my paltry possessions fairly often and that I find upsets me a bit. […] uprooting, no matter how small a plant you are, is a trauma.

I report on these experiences of having to move house in further detail in a just-released research paper.

Read more:

What sort of housing do older Australians want and where do they want to live?

It is time for reform

Our federal government needs to permanently raise the JobSeeker payment and act on housing affordability to give low-income renters a fighting chance.

At a state level, it is time to end “no grounds” evictions. “With cause” measures, as recently introduced in Victoria, better balance tenants’ needs for housing security with the rights of landlords to repurpose properties when required.

We also need quantified minimum rental housing standards. New Zealand’s Healthy Homes standards can be a model for us. These standards ensure only properties that are healthy and sound go to market.

Read more:

Chilly house? Mouldy rooms? Here's how to improve low-income renters’ access to decent housing

The number of older Australians who rent is projected to increase over the next decade as home ownership levels decline. The stories of older women in the private rental sector are a warning about the risks that declining housing affordability and rental insecurity pose to this growing group. They are the “canary in the coalmine” for Australia’s housing system.

Authors: Emma Power, Senior Research Fellow, Geography and Urban Studies, Western Sydney University