Why coronavirus will deepen the inequality of our suburbs

- Written by Carl Grodach, Professor and Director of Urban Planning & Design, Monash University

COVID-19 and the growing recession concentrated in the services sector will not just increase social inequality, but accelerate the growing spatial divide in our cities. As our new research report shows, the pandemic’s impacts reinforce the ongoing trend towards the suburbanisation of inequality.

There are two reasons for this. First, the industries vulnerable to the economic impacts of COVID-19 lockdowns rely heavily on low-wage, part-time employment. Second, the inner suburbs are home to the largest concentration of COVID-vulnerable workers.

Read more: Rapid growth is widening Melbourne's social and economic divide

If we do not act now, more people will get pushed out of inner areas rich in jobs and amenities to lower-cost outer suburbs with poor access to jobs and community services.

Which industries and workers are vulnerable?

Our research analyses where people employed in the industries most vulnerable to COVID-19 lockdowns live and the kind of work they do. We map vulnerable employment areas in all suburbs of Australia’s five largest capital cities. We then examine the characteristics of people in vulnerable employment living in all suburbs of Australia’s current coronavirus hotspot, metropolitan Melbourne.

We define vulnerable employment based on a detailed review of industries with one-third or more firms reporting reduced worker hours one week after the first COVID-19 lockdown (March 30 2020). These firms are mainly in the consumer, travel and community services sectors. They employ people working in accommodation and food, arts and entertainment, education, “non-essential” health care, retail and transport.

Read more: How the coronavirus recession puts service workers at risk

We profile the characteristics of vulnerable workers in each of these sub-industries and by suburb. We classify suburbs (using SA2 level data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics) by share of vulnerable employment based on the worker’s place of usual residence.

Many at-risk workers live in inner suburbs

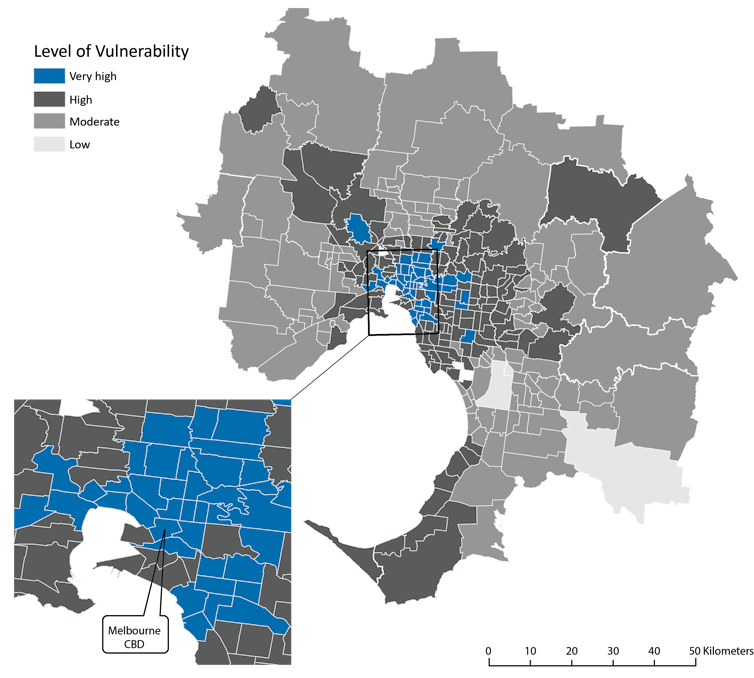

As the map below shows, the largest shares of vulnerable workers live in Melbourne’s inner suburbs.

Source: ABS (2016) Census data, by place of residence at SA2 level. Map by Declan Martin and Alexa Gower, Author provided

Vulnerability levels clearly diminish moving outward from the city centre. In other words, many vulnerable workers live in some of the highest-rent suburbs.

On average, the share of vulnerable workers in the very high vulnerability suburbs is 32.2% of employed residents. The figure exceeds 40% in some of these areas.

Workers likely to be forced to move

Living in the inner suburbs, combined with the nature of their jobs, puts many COVID-vulnerable workers at high risk of displacement.

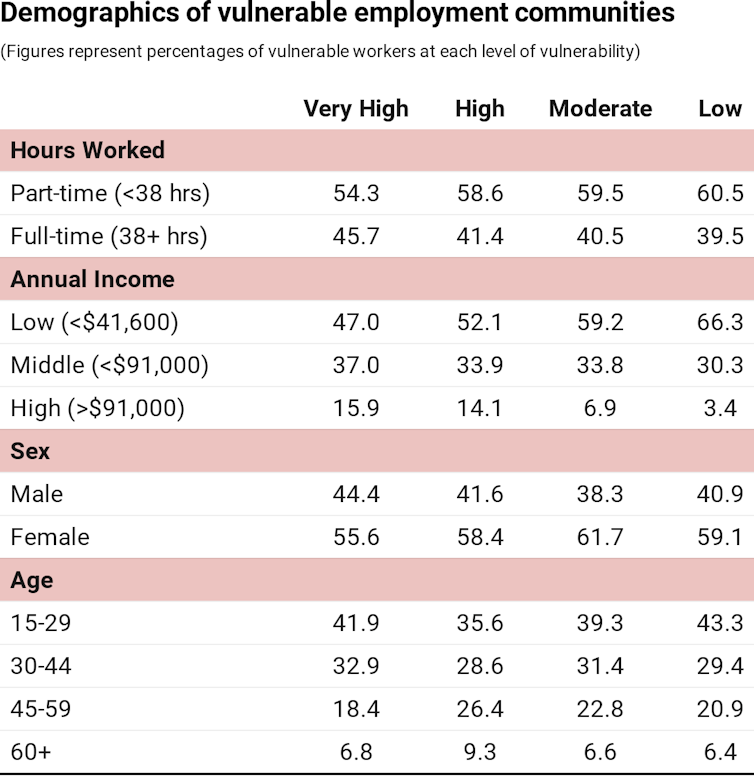

In the very high vulnerability suburbs, 47% of vulnerable workers are on low or very low incomes. And 54.3% work part-time (less than 38 hours a week). A large proportion (41.9%) are aged under 30 and about one-third are 30-44.

In fact, over half (53.5%) of the vulnerable workforce living in very high-vulnerability suburbs hold jobs in the most precarious, low-wage consumer services industries – accommodation and food services and retail and personal services. Another 30% work in arts, entertainment and education.

Suppressed consumer demand will not only have short-run employment impacts, but might permanently alter consumption patterns. The result would be enduring business closures and job losses for workers who live in these areas.

To make ends meet, many of those facing job loss and other employment pressures such as reduced hours will seek more affordable housing in the middle and outer suburbs.

However, although the outer areas are now home to the smallest proportion of vulnerable workers, the vulnerable workers that live there tend to be worse off. Just over 66% are on low or very low incomes and 60% work part-time.

As a result, the migration of COVID-vulnerable workers to the outer areas will add to the existing concentration of spatial inequality in Greater Melbourne.

Source: ABS (2016) Census data, by place of residence at SA2 level. Map by Declan Martin and Alexa Gower, Author provided

Vulnerability levels clearly diminish moving outward from the city centre. In other words, many vulnerable workers live in some of the highest-rent suburbs.

On average, the share of vulnerable workers in the very high vulnerability suburbs is 32.2% of employed residents. The figure exceeds 40% in some of these areas.

Workers likely to be forced to move

Living in the inner suburbs, combined with the nature of their jobs, puts many COVID-vulnerable workers at high risk of displacement.

In the very high vulnerability suburbs, 47% of vulnerable workers are on low or very low incomes. And 54.3% work part-time (less than 38 hours a week). A large proportion (41.9%) are aged under 30 and about one-third are 30-44.

In fact, over half (53.5%) of the vulnerable workforce living in very high-vulnerability suburbs hold jobs in the most precarious, low-wage consumer services industries – accommodation and food services and retail and personal services. Another 30% work in arts, entertainment and education.

Suppressed consumer demand will not only have short-run employment impacts, but might permanently alter consumption patterns. The result would be enduring business closures and job losses for workers who live in these areas.

To make ends meet, many of those facing job loss and other employment pressures such as reduced hours will seek more affordable housing in the middle and outer suburbs.

However, although the outer areas are now home to the smallest proportion of vulnerable workers, the vulnerable workers that live there tend to be worse off. Just over 66% are on low or very low incomes and 60% work part-time.

As a result, the migration of COVID-vulnerable workers to the outer areas will add to the existing concentration of spatial inequality in Greater Melbourne.

Source: ABS 2016 Census data, by place of residence at the SA2 level, Author provided

Read more:

Private renters are doing it tough in outer suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne

What can be done about this?

COVID-19 puts people working in low-end service jobs and the creative and educational services at high risk of losing their jobs. Those who manage to live in the high-cost inner suburbs are now particularly vulnerable.

Read more:

Coronavirus: 3 in 4 Australians employed in the creative and performing arts could lose their jobs

It is therefore crucial to expand rather than retract the JobKeeper and JobSeeker programs. Proposed cuts to JobSeeker are estimated to push 370,000 Australians into poverty, 123,000 in Victoria alone. In tandem, we need interim policy in the rental housing market to defuse the impending “rent bomb” of tenants facing eviction if they can’t pay the accumulated debt of deferred rent.

Longer-term strategies are also needed. We must confront the reality that many service sector jobs will not return.

This requires investment in skills-building courses tied to strengthening the recovery of TAFEs and universities, particularly in areas like “essential manufacturing” – medical supplies, recycling, food – and communications technologies. JobTrainer is a good start.

Given the spatial dimensions of the crisis, place-based programs are crucial too. Preserving inner suburban industrial land can play a significant role in small enterprise start-ups, firm expansion and job creation. Inner industrial districts provide a flexible mix of space that allows businesses to grow and add quality jobs in place.

Read more:

Three ways to fix the problems caused by rezoning inner-city industrial land for mixed-use apartments

At the same time, policymakers can better develop community infrastructure and employment hubs in the outer suburbs. Community hubs provide flexible, multipurpose spaces that cater to various community needs. These services range from youth, aged care and health facilities to collaborative workspaces and settings for workforce training providers.

While COVID-19 is clearly taking an immediate toll on the health and economies of our cities, we need a conversation about the longer-term impacts and responses.

Source: ABS 2016 Census data, by place of residence at the SA2 level, Author provided

Read more:

Private renters are doing it tough in outer suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne

What can be done about this?

COVID-19 puts people working in low-end service jobs and the creative and educational services at high risk of losing their jobs. Those who manage to live in the high-cost inner suburbs are now particularly vulnerable.

Read more:

Coronavirus: 3 in 4 Australians employed in the creative and performing arts could lose their jobs

It is therefore crucial to expand rather than retract the JobKeeper and JobSeeker programs. Proposed cuts to JobSeeker are estimated to push 370,000 Australians into poverty, 123,000 in Victoria alone. In tandem, we need interim policy in the rental housing market to defuse the impending “rent bomb” of tenants facing eviction if they can’t pay the accumulated debt of deferred rent.

Longer-term strategies are also needed. We must confront the reality that many service sector jobs will not return.

This requires investment in skills-building courses tied to strengthening the recovery of TAFEs and universities, particularly in areas like “essential manufacturing” – medical supplies, recycling, food – and communications technologies. JobTrainer is a good start.

Given the spatial dimensions of the crisis, place-based programs are crucial too. Preserving inner suburban industrial land can play a significant role in small enterprise start-ups, firm expansion and job creation. Inner industrial districts provide a flexible mix of space that allows businesses to grow and add quality jobs in place.

Read more:

Three ways to fix the problems caused by rezoning inner-city industrial land for mixed-use apartments

At the same time, policymakers can better develop community infrastructure and employment hubs in the outer suburbs. Community hubs provide flexible, multipurpose spaces that cater to various community needs. These services range from youth, aged care and health facilities to collaborative workspaces and settings for workforce training providers.

While COVID-19 is clearly taking an immediate toll on the health and economies of our cities, we need a conversation about the longer-term impacts and responses.

Authors: Carl Grodach, Professor and Director of Urban Planning & Design, Monash University

Read more https://theconversation.com/why-coronavirus-will-deepen-the-inequality-of-our-suburbs-143432