Humans are encroaching on Antarctica’s last wild places, threatening its fragile biodiversity

- Written by Rachel Leihy, PhD candidate, Monash University

Since Western explorers discovered Antarctica 200 years ago, human activity has been increasing. Now, more than 30 countries operate scientific stations in Antarctica, more than 50,000 tourists visit each year, and new infrastructure continues to be developed to meet this rising demand.

Determining if our activities have compromised Antarctica’s wilderness has, however, remained difficult.

Our study, published today in Nature, seeks to change that. Using a new “ecological informatics” approach, we’ve drawn together every available recorded visit by humans to the continent, over its 200 year history.

We found human activity across Antarctica has been extensive, especially in the ice-free and coastal areas, but that’s where most biodiversity is found. This means wilderness areas – parts of the continent largely untouched by human activity – do not capture many of the continent’s important biodiversity sites.

Historical and contemporary human activity on Deception Island.

SL Chown

Historical and contemporary human activity on Deception Island.

SL Chown

One of the world’s largest intact wildernesses

So just how large is the Antarctic wilderness? For the first time, our study calculated this area and how much biodiversity it captures. And, like all good questions, the answer is “that depends”.

If we think of Antarctica in the same way as every other continent, then the whole of Antarctica is a wilderness. It has no farms, no cities, no suburbs, no malls, no factories. And for a continent so large, it has very few people.

Antarctica’s wilderness should be held to a higher standard.

SL Chown

Antarctica’s wilderness should be held to a higher standard.

SL Chown

But Antarctica is too different to compare to other continents – it should be held to a higher standard. And so we define “wilderness” as the areas that aren’t highly impacted by people. This would exclude, for example, tourist areas and scientific stations. And under this definition, the wilderness area is still large.

It’s about 13,598,148 square kilometres, or more than 99% of the continent. Only the wilderness in the vast forested areas of the far Northern Hemisphere is larger. Roughly, this area is nearly twice the size of Australia.

Read more: Marine life found in ancient Antarctica ice helps solve a carbon dioxide puzzle from the ice age

On the other hand, the inviolate areas (places free from human interference) that the Antarctic Treaty Parties are obliged to identify and protect are dwindling rapidly.

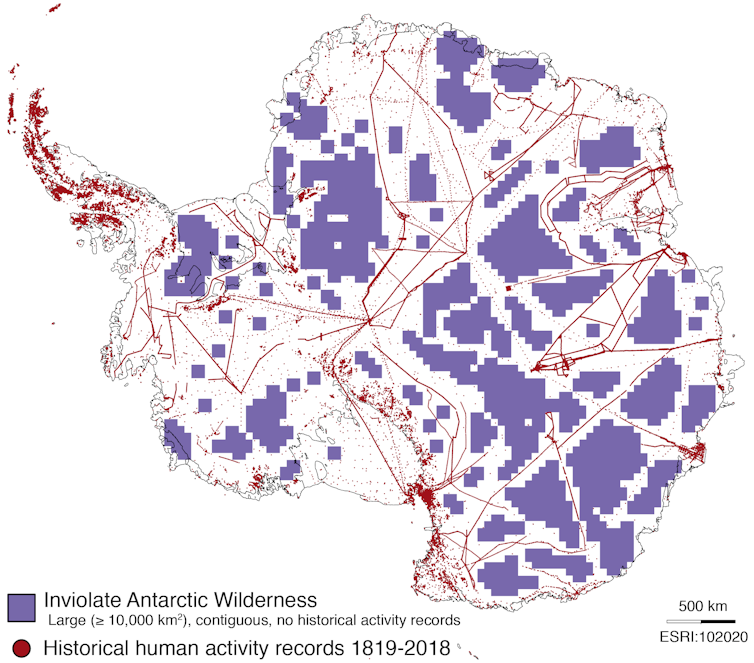

Our analyses suggest less than 32% of the continent includes large, unvisited areas. And even that’s an overestimate. Not all visits have been recorded, and several new traverses – crossing large tracts of unvisited areas – are being planned.

Human activity has been extensive across Antarctica, but large areas with no visitation record might still exist across central parts of the continent.

Leihy et al. 2020 Nature

Human activity has been extensive across Antarctica, but large areas with no visitation record might still exist across central parts of the continent.

Leihy et al. 2020 Nature

Wilderness areas have poor biodiversity value

If so much of the continent remains “wild”, how much of Antarctica’s biodiversity lives within these areas?

Surprisingly few sites considered really important for Antarctic biodiversity are represented in the “un-impacted” wilderness area.

For example, only 16% of the continent’s Important Bird Areas (areas identified internationally as critical for bird conservation) are located in wilderness areas. And only 25% of protected areas established for their species or ecosystem value, and less than 7% of sites with recorded species, are in wilderness areas.

This outcome is surprising because wilderness areas elsewhere, like the Amazon rainforest, are typically valued as crucial habitat for biodiversity.

Ice-free areas are critical habitat for Antarctic biodiversity, like Adélie penguins, and frequently visited by people as well.

SL Chown

Ice-free areas are critical habitat for Antarctic biodiversity, like Adélie penguins, and frequently visited by people as well.

SL Chown

Inviolate areas have seemingly even less biodiversity value. This is because people have mostly had to visit Antarctic sites to collect species data.

In the future, remote sensing technologies might allow us to investigate and monitor pristine areas without setting foot in them. But for now, most of our knowledge of Antarctic species comes from places that have been impacted to some extent by people.

How does human activity threaten Antarctic biodiversity?

Antarctica’s remaining wilderness areas need urgent protection from increasing human activity.

Even passing human disturbance can impact the biodiversity and wilderness value of sites. For example, sensitive vegetation and soil communities can take years to recover from trampling.

Increasing movement around the continent also increases the risk people will transfer species between isolated regions, or introduce new alien species to Antarctica.

Expanding the existing network of Antarctic protected areas can secure remaining wilderness areas into the future.

SL Chown

Expanding the existing network of Antarctic protected areas can secure remaining wilderness areas into the future.

SL Chown

So how can we protect it?

Protecting the Antarctic wilderness could be achieved by expanding the existing Antarctic Specially Protected Areas network to include more wilderness and inviolate areas where policymakers would limit human activity.

When planning how we’ll use Antarctica in the future, we could also consider the trade off between the benefits of science and tourism activities, and the value of retaining pristine wilderness and inviolate areas.

Read more: Microscopic animals are busy distributing microplastics throughout the world's soil

This could be done explicitly through the environmental impact assessments required for activities in the region. Currently, impacts on the wilderness value of sites are rarely considered.

We have an opportunity in Antarctica to protect some of the world’s most intact and undisturbed environments, and prevent further erosion of Antarctica’s remarkable wilderness value.

Ross Sea Region, Antarctica. Few sites considered really important for Antarctic biodiversity are represented in the wilderness area.

SL Chown

Ross Sea Region, Antarctica. Few sites considered really important for Antarctic biodiversity are represented in the wilderness area.

SL Chown

Authors: Rachel Leihy, PhD candidate, Monash University