It's one thing to build war fighting capability, it's another to build industrial capability

- Written by Graeme Dunk, PhD Candidate, Australian National University

Amid fanfare last week at the start of the new financial year the government promised to invest A$270 billion over a decade to upgrade the defence force.

It said a side benefit would be a stronger local defence industry and “more high-tech Australian jobs”.

The prime minister’s statement hastened to add that it was already strong

Australia’s defence industry is growing with over 4,000 businesses employing approximately 30,000 staff. An additional 11,000 Australian companies directly benefit from Defence investment and, when further downstream suppliers are included, the benefits flow to approximately 70,000 workers.

But the Australian part of Australia’s defence industry is small and getting smaller.

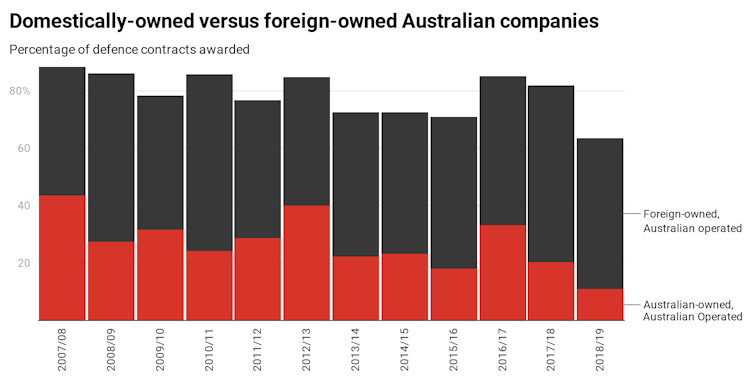

My analysis of contracts listed on the government’s Austender website shows that while the proportion of defence department contracts awarded to Australian operated firms is usually well above 60%, the proportion awarded to firms that are both Australian operated and owned is much lower, presently 11%.

Austender, authors calculations

It means that while Australians are being employed on defence department projects, the use of Australian firms that develop and own intellectual property is at a near-record low.

Other analysis of the same data shows that the value of the contracts awarded to Australian owned companies is increasingly lower than for foreign owned companies.

This is backed up by the annual Australian Defence Magazine survey of the top 40 defence contractors.

Despite the fact that in the most recent survey two of the biggest contractors declined to take part – the French-owned Naval Group Australia, which has the contract for the Future Submarine program, and the US-owned Raytheon – it has the advantage of including subcontracting relationships not shown in Austender.

The survey finds that while the amount of work done by Australian-controlled companies has held up since 2015, it has been increasingly subcontracted to foreign-owned prime contractors.

This subordinate role has important implications for the health of Australia’s industry and national resilience.

For industry it means that Australia is denied the full economic benefits that would come from designing and running projects and owning the intellectual property.

For national resilience it increases Australia’s exposure to events outside its control.

Read more:

Scott Morrison pivots Australian Defence Force to meet more threatening regional outlook

If foreign-controlled firms withdraw, withhold or otherwise redirect assistance (or if they are directed to do so by foreign governments) it is harder for Australia’s industry to pick up the slack.

The supply chain interruptions caused by COVID-19 have highlighted these vulnerabilities.

Brent Clark, the national chief executive of the Australian Industry and Defence Network says he was “shocked to learn how many of our supplies are sourced from overseas and how quickly those supplies became hard to access as soon as overseas countries required them for their own purposes”.

He says the industry is not asking for a free ride, but it does want to be able to compete for contracts in a fair and equitable manner.

Read more:

Defence update: in an increasingly dangerous neighbourhood, Australia needs a stronger security system

This isn’t to suggest Australia needs to it do all. Complete self-sufficiency in defence is unrealistic.

But it would deepen Australia’s war fighting capability if Australian firms had the ability to to supply and maintain much of the essential equipment we will need to use.

And it would strengthen our ability to deal with other crises. COVID-19 has shown that industrial capability and resilience are intrinsically linked.

The Government’s rhetoric and policies support home-grown growth. All that is needed now is commitment backed up by accountability.

Louisa Minney, defence consultant, business analyst and company director, contributed to this article.

Austender, authors calculations

It means that while Australians are being employed on defence department projects, the use of Australian firms that develop and own intellectual property is at a near-record low.

Other analysis of the same data shows that the value of the contracts awarded to Australian owned companies is increasingly lower than for foreign owned companies.

This is backed up by the annual Australian Defence Magazine survey of the top 40 defence contractors.

Despite the fact that in the most recent survey two of the biggest contractors declined to take part – the French-owned Naval Group Australia, which has the contract for the Future Submarine program, and the US-owned Raytheon – it has the advantage of including subcontracting relationships not shown in Austender.

The survey finds that while the amount of work done by Australian-controlled companies has held up since 2015, it has been increasingly subcontracted to foreign-owned prime contractors.

This subordinate role has important implications for the health of Australia’s industry and national resilience.

For industry it means that Australia is denied the full economic benefits that would come from designing and running projects and owning the intellectual property.

For national resilience it increases Australia’s exposure to events outside its control.

Read more:

Scott Morrison pivots Australian Defence Force to meet more threatening regional outlook

If foreign-controlled firms withdraw, withhold or otherwise redirect assistance (or if they are directed to do so by foreign governments) it is harder for Australia’s industry to pick up the slack.

The supply chain interruptions caused by COVID-19 have highlighted these vulnerabilities.

Brent Clark, the national chief executive of the Australian Industry and Defence Network says he was “shocked to learn how many of our supplies are sourced from overseas and how quickly those supplies became hard to access as soon as overseas countries required them for their own purposes”.

He says the industry is not asking for a free ride, but it does want to be able to compete for contracts in a fair and equitable manner.

Read more:

Defence update: in an increasingly dangerous neighbourhood, Australia needs a stronger security system

This isn’t to suggest Australia needs to it do all. Complete self-sufficiency in defence is unrealistic.

But it would deepen Australia’s war fighting capability if Australian firms had the ability to to supply and maintain much of the essential equipment we will need to use.

And it would strengthen our ability to deal with other crises. COVID-19 has shown that industrial capability and resilience are intrinsically linked.

The Government’s rhetoric and policies support home-grown growth. All that is needed now is commitment backed up by accountability.

Louisa Minney, defence consultant, business analyst and company director, contributed to this article.

Authors: Graeme Dunk, PhD Candidate, Australian National University