Is protesting during the pandemic an 'essential' right that should be protected?

- Written by Maria O'Sullivan, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, and Deputy Director, Castan Centre for Human Rights Law, Monash University

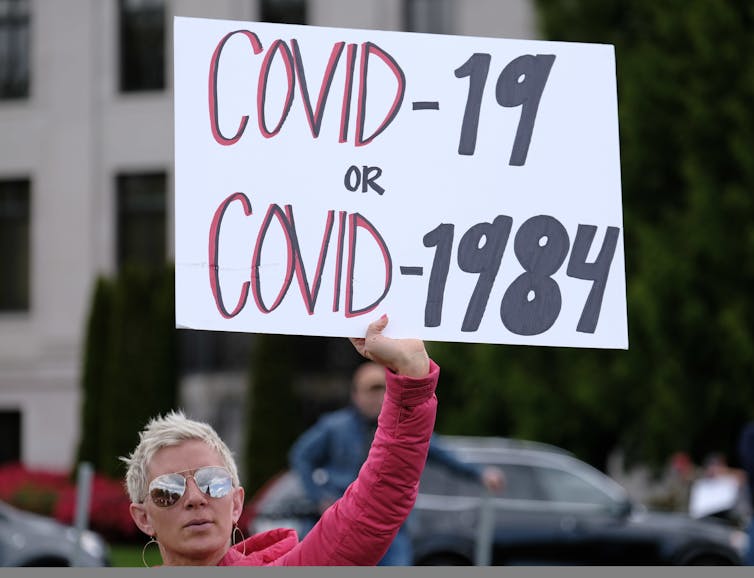

Protests are increasingly breaking out around the world as people begin to chafe against lockdown restrictions to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

In the US, President Donald Trump is fuelling the spread of protest movements nationwide with tweets to “liberate” certain states. This month, car convoy protests were also held here in Australia, as well as in Poland and Brazil.

Hundreds of Brazilians have protested in major cities against the country’s lockdown measures.

Cris Faga/SIPA USA

Hundreds of Brazilians have protested in major cities against the country’s lockdown measures.

Cris Faga/SIPA USA

In Germany, some 300 protesters gathered in a main square in Berlin to protest COVID-19 restrictions, leading to many arrests.

Read more: Coronavirus versus democracy: 5 countries where emergency powers risk abuse

Protest is one of the most important ways we can express disagreement with government action. However, the ability of people to protest in an emergency situation such as the current pandemic is very unclear.

Can we protest outside if we are in cars, maintaining social distancing, for instance? Is protest considered an “essential” activity?

Protests have broken out in the US from Washington state to North Carolina. Some cities have begun fining people.

Alex Milan Tracy/Sipa USA

Protests have broken out in the US from Washington state to North Carolina. Some cities have begun fining people.

Alex Milan Tracy/Sipa USA

What’s at stake when protests are disallowed?

On April 10, activists staged a car convoy protest in Melbourne to highlight the plight of refugees in detention who face a heightened risk of contracting COVID-19 due to overcrowded conditions.

Despite the fact everyone was social distancing in cars, police arrested one man and fined 26 others a total of $43,000 because they were not in public for an allowable reason (for instance, work, exercise, shopping for essentials or caregiving).

The ability to voice dissent is vital for a functioning democracy. It is therefore arguable that people should be able to protest against what they see as government overreach in social restrictions or the enforcement of these rules by police.

Read more: Pandemic policing needs to be done with the public's trust, not confusion

This is especially true if one considers the role of protesters in giving voice to those who are marginalised or unable to demonstrate publicly themselves, such as asylum seekers in detention.

These protests are different in that they are not about the restrictions themselves or disagreement with policymakers; rather, they are in response to a legitimate health concern and questions of violations of human rights (the right to health and liberty).

Asylum seekers protesting their continued detention during the pandemic in Brisbane.

Dan Peled/AAP

Asylum seekers protesting their continued detention during the pandemic in Brisbane.

Dan Peled/AAP

Is limiting protest against our constitution?

In many democratic countries, COVID-19 restrictions must be balanced with protections enshrined in human rights charters.

Although Australia does not have a human rights charter at the federal level and there is no guaranteed “right to protest”, we do have a concept called the “implied freedom of political communication”.

This implied freedom stems from provisions in our constitution about representative government, and has been quite influential in protecting certain forms of protest. For instance, in 2017, former Australian Greens leader Bob Brown successfully challenged Tasmania’s anti-protest law in the High Court, arguing it targeted the freedom of political expression and was therefore unconstitutional.

Read more: Bob Brown wins his case, but High Court leaves the door open to laws targeting protesters

To determine if this implied freedom is being curtailed, there are several key points to examine.

Does the law impinge on political discussion?

Does it serve a legitimate purpose?

And is it disproportionate in its impact?

As part of the proportionality question, we can examine whether there is an alternative practical or legislative means of achieving the purpose of the law – in this case, reducing the spread of a virus – that has a less burdensome effect on the implied freedom of political communication.

If we apply these tests to the coronavirus restrictions, it is quite clear they do limit our political expression, but also serve a legitimate purpose (by ensuring the safety and well-being of the community).

Read more: Why an Australian charter of rights is a matter of national urgency

However, I would argue the requirements imposed by the law are not proportionate. Specifically, I do believe there is way to protect public health while simultaneously allowing a form of protest.

Instead of a wholesale ban on protesting, for instance, the restrictions could be changed to allow protest as a permitted reason to leave home if protesters observe social distancing rules. This could include limiting cars to members from the same household or to a maximum of two people in states where gatherings are severely restricted.

Israelis protesting against government corruption while maintaining social distancing.

Abir Sultan/EPA

Israelis protesting against government corruption while maintaining social distancing.

Abir Sultan/EPA

Aren’t there other ways to protest?

Online or virtual protests are a possibility. Climate change activist Greta Thunberg has recommended people avoid mass gatherings during the pandemic and instead engage in online campaigns and digital strikes.

However, one of the hallmarks of effective protest is its public, visual impact. And often media coverage of protests is a means of garnering greater public support. This is why taking over city streets or occupying buildings has been a key strategy of protest groups such as Extinction Rebellion.

In this light, online protests are not a substitute for traditional street protests, as they will not necessarily have the same potential to drive change – which is often the whole reason for protesting in the first place.

So, as the pandemic continues, we are likely to see more people protesting on the streets – not fewer. And it is the responsibility of governments to avoid responding with increasingly heavy-handed tactics, such as widespread arrests and fines, as this could inflame public anger even more and further call into question the legality of the restrictions.

During this time, we also need to reflect on the way our legal system operates in Australia to ensure the COVID-19 restrictions do not disproportionately affect the most marginalised in our community. And, ultimately, we need to ask ourselves whether our fundamental human rights protections could be strengthened by a federal charter of human rights.

Authors: Maria O'Sullivan, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, and Deputy Director, Castan Centre for Human Rights Law, Monash University