Lower growth, tiny surplus in MYEFO budget update

- Written by Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

The government has shaved its forecasts for both economic growth and the projected surplus for this financial year in its budget update released on Monday.

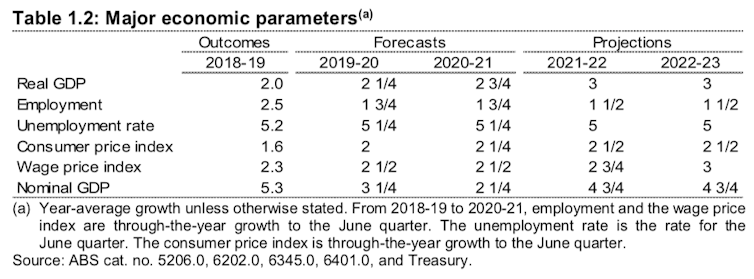

The Australian economy is now expected to grow by only 2.25% in 2019-20, compared with the 2.75% forecast in the April budget.

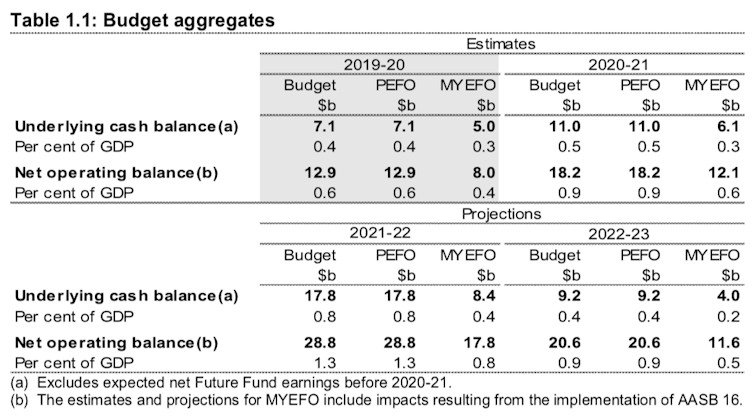

The projected surplus has been revised down from A$7.1 billion at budget time to $5 billion for this financial year.

By 2022-23 the surplus is projected to be tiny A$4 billion, a mere one fifth of one per cent of GDP, less than half the $9.2 billion projected in April.

Combined, $21.6 billion has been slashed from projected surpluses over the coming four years.

The revenue estimates have also been slashed, down from the pre-election economic and fiscal outlook (PEFO) by about $3 billion in 2019-20 and $32.6 billion over the forward estimates.

The changes this financial year reflect downgrades to superannuation fund taxes, the GST and non-tax receipts. The downgrade in later years reflects changed forecasts for individual taxes, company tax and GST.

The official documents sought to put as positive a spin as possible on the worse economic figures:

Australia’s economy continues to show resilience in the face of weak momentum in the global economy, as well as domestic challenges such as the devastating effects of drought and bushfires.

While economic activity has continued to expand, these factors have resulted in slower growth than had been expected at PEFO.

The revised figures forecast growth will be 2.75% next financial year.

The impact of the drought is reflected in the fact farm GDP is expected to fall to the lowest level seen since 2007-08 in the millenium drought.

The downgrades will fuel calls already being made by the opposition and some stakeholders and commentators for economic stimulus.

But the government, which since the budget has brought forward some infrastructure and announced spending on aged care and drought assistance, is continuing to resist pressure for stimulus now, wishing to hold out until budget time.

The budget update - formally called the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook (MYEFO) - contains more bad news for workers’ wages.

Wages are forecast to rise in 2019-20 by 2.5%, compared with the forecast of 2.75% in the budget.

The revenue estimates have also been slashed, down from the pre-election economic and fiscal outlook (PEFO) by about $3 billion in 2019-20 and $32.6 billion over the forward estimates.

The changes this financial year reflect downgrades to superannuation fund taxes, the GST and non-tax receipts. The downgrade in later years reflects changed forecasts for individual taxes, company tax and GST.

The official documents sought to put as positive a spin as possible on the worse economic figures:

Australia’s economy continues to show resilience in the face of weak momentum in the global economy, as well as domestic challenges such as the devastating effects of drought and bushfires.

While economic activity has continued to expand, these factors have resulted in slower growth than had been expected at PEFO.

The revised figures forecast growth will be 2.75% next financial year.

The impact of the drought is reflected in the fact farm GDP is expected to fall to the lowest level seen since 2007-08 in the millenium drought.

The downgrades will fuel calls already being made by the opposition and some stakeholders and commentators for economic stimulus.

But the government, which since the budget has brought forward some infrastructure and announced spending on aged care and drought assistance, is continuing to resist pressure for stimulus now, wishing to hold out until budget time.

The budget update - formally called the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook (MYEFO) - contains more bad news for workers’ wages.

Wages are forecast to rise in 2019-20 by 2.5%, compared with the forecast of 2.75% in the budget.

Employment growth remains at the earlier forecast level of 1.75% for this financial year, but the unemployment rate is slightly up in the latest forecast, from 5% at budget time to 5.25% in the update.

In its bring forward and funding of new projects, the government is putting an extra $4.2 billion over the forward estimates into transport infrastructure projects.

Its extra spending on aged care will be almost $624 million over four years, in its initial response to the royal commission. This is somewhat higher than the $537 million announced by Scott Morrison in November.

While the projected surplus has been squeezed, the government continues to highlight the priority it gives it, saying that despite the revenue write downs, it expects cumulative surpluses over $23.5 billion over forward estimates.

Spending growth is estimated to be 1.3% annual average in real terms over the forward estimates. Payments as a share of GDP is estimated at 24.5% this financial year, reducing to 24.4% by 2022-23, which is below the 30 year average.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said the update showed “the government is living within its means, and paying down Labor’s debt”.

He said “the surplus has never been an end in itself, but a means to an end. An end which is to reduce interest payments to free up money to be spent elsewhere across the economy.”

The government’s economic plan was “delivering continued economic growth and a stronger budget position.

"MYEFO demonstrates that we have the capacity and the flexibility to invest in the areas that the public need most.”

Shadow treasurer Jim Chalmers said the update showed the government’s economic credibility was destroyed. At its core, there were “two humiliating confessions - the economy is much weaker and the government has absolutely no idea and no plan to turn things around”.

Chalmers said Morrison and Frydenberg “couldn’t give a stuff that Australians are facing higher unemployment and weaker wages and slower growth.

"If they cared enough about the workers and families of this country, they would stop sitting on their hands and they would come up with an actual plan to turn around an economy which is floundering on their watch.”

Employment growth remains at the earlier forecast level of 1.75% for this financial year, but the unemployment rate is slightly up in the latest forecast, from 5% at budget time to 5.25% in the update.

In its bring forward and funding of new projects, the government is putting an extra $4.2 billion over the forward estimates into transport infrastructure projects.

Its extra spending on aged care will be almost $624 million over four years, in its initial response to the royal commission. This is somewhat higher than the $537 million announced by Scott Morrison in November.

While the projected surplus has been squeezed, the government continues to highlight the priority it gives it, saying that despite the revenue write downs, it expects cumulative surpluses over $23.5 billion over forward estimates.

Spending growth is estimated to be 1.3% annual average in real terms over the forward estimates. Payments as a share of GDP is estimated at 24.5% this financial year, reducing to 24.4% by 2022-23, which is below the 30 year average.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said the update showed “the government is living within its means, and paying down Labor’s debt”.

He said “the surplus has never been an end in itself, but a means to an end. An end which is to reduce interest payments to free up money to be spent elsewhere across the economy.”

The government’s economic plan was “delivering continued economic growth and a stronger budget position.

"MYEFO demonstrates that we have the capacity and the flexibility to invest in the areas that the public need most.”

Shadow treasurer Jim Chalmers said the update showed the government’s economic credibility was destroyed. At its core, there were “two humiliating confessions - the economy is much weaker and the government has absolutely no idea and no plan to turn things around”.

Chalmers said Morrison and Frydenberg “couldn’t give a stuff that Australians are facing higher unemployment and weaker wages and slower growth.

"If they cared enough about the workers and families of this country, they would stop sitting on their hands and they would come up with an actual plan to turn around an economy which is floundering on their watch.”

Authors: Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

Read more http://theconversation.com/lower-growth-tiny-surplus-in-myefo-budget-update-128920