Cut throat competition, 'corporate-speak' and dark ironies: two new five-year arts plans

- Written by Jo Caust, Associate Professor and Principal Fellow (Hon), University of Melbourne

A new five-year South Australian Arts Plan was launched this week. But there was a strange disconnect between an acknowledgement by the consultants of a problem in the state - given a significant reduction in arts funding and support services over the past year in particular - and limited means of addressing this going forward.

In fact, at the outset, the consultants note that their review, “does not make recommendations requiring significant additional government expenditure”.

In other words, despite the evidence of a sector that is struggling to make sense of cuts and reductions across the spectrum, the review has no intention of recommending changes that will address this.

The review notes “some concern at the loss of an independent arts department”. In December 2018, Arts SA as an independent government entity was dissolved by the government and the skeleton staff remaining were transferred to the Premier’s Department. Arts organisations are now embedded across several departments meaning there is now no one body charged with responsibility for the arts across SA.

Increasing the pressure

While the plan’s authors note problematic aspects of the SA arts scene (such as its over-reliance on festivals and lack of cultural infrastructure) they do not make strong recommendations as to how to fix this, aside from voicing support for a new concert hall.

Instead, they put the pressure back on the arts sector itself, arguing for more structural collaboration (such as better cooperation between the Adelaide Festival Centre and its users) and more sharing of resources. They also recommend other agents get involved in the arts to cover the shortfall in government support. That is, bring in the philanthropists and the private sector.

SA Premier Steven Marshall announcing Adelaide Festival’s new three year partnership with the French Festival d’ Aix-en-Provence in March this year.

Kelly Barnes/AAP

SA Premier Steven Marshall announcing Adelaide Festival’s new three year partnership with the French Festival d’ Aix-en-Provence in March this year.

Kelly Barnes/AAP

The reality is that this does not work in a state with no corporate head offices and limited philanthropic engagement. Nevertheless, the review recommends the national organisation Creative Partnerships Australia re-open an office in SA (paid for, probably, by South Australia), despite the national organisation closing it themselves several years ago.

Creative disconnection

Also last week, the Australia Council released its next five-year strategy, titled Creativity Connects Us. There is a serious attempt within the strategy to recognise that the arts cover a broad spectrum of cultural activity - not just elite activity. It acknowledges the diversity of Australia’s culture and highlights the extraordinary length and depth of First Nations’ cultural practices.

The strategy supports “equity of opportunity and access in our creative expression, workforce, leaders and audiences”. A key performance criterion for measuring this is, “supporting at least 200 culturally diverse applications with total funding of $13 million provided per year”.

But there is a gap between rhetoric and practice. The Council’s funding for the arts was $189.3 million in 2017-18, according to its annual report. More than $111 million or around 58% of this funding goes to arguably “elite” arts activity under the major performing arts framework.

If $13 million of this was allocated towards cultural diverse activity as noted, that represents around 7% of the Council’s total arts funding. This percentage does not reflect the cultural diversity of Australia, given in 2018 the ABS recorded that 29% of the population were born overseas.

Funding rejected

Both plans use “corporate speak” and adopt a neo-liberal view of the arts which frames government arts funding as “investments”. While arts activities, organisations and artists themselves are always in competition with each other for funding, the current climate appears to exacerbate this. Further, the continued emphasis on the arts as a framing for commercial activity and as a minor player in the creative industries, serves to undermine any belief that healthy societies benefit from arts practice and should therefore generously support them.

For example, the week before the Australia Council published its new plan touting how “its investment and initiatives have grown the profile and reach of Australian arts experiences,” it had rejected hundreds of organisations for future funding through its latest funding round.

Out of 412 applications from small to medium organisations across all art forms for four-year, general grant funding, 250 have been informed they were not successful.

Of the 162 remaining, only around 100 will eventually be successful. The same scenario occurred in May 2016, on a day known as Black Friday in the arts sector, when 65 arts organisations lost their funding.

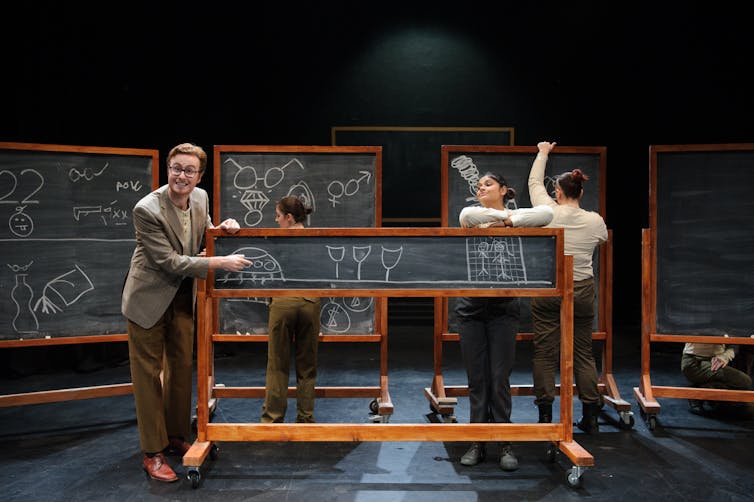

Performers in Theatreworks’ recent production of Slaughterhouse Five: Sam Barson, Talia Zipper Simran Giria, and Caitlin Duff.

Sarah Walker

Performers in Theatreworks’ recent production of Slaughterhouse Five: Sam Barson, Talia Zipper Simran Giria, and Caitlin Duff.

Sarah Walker

This latest round has meant loss of funding for Theatreworks in Melbourne, AustralianPlays.org in Tasmania (a resource repository for Australian plays) and the journal Overland. Others have noted the art form of literature now receives less funding as an overall percentage than it did 40 years ago.

Making arts organisations with totally different mandates compete against each other, for a diminishing amount of funding, makes no sense. Where is the rationale here for building a strong and healthy arts sector?

An ironic feature of the South Australian Arts Plan is the inclusion of the theatre company Slingsby as an example of a wonderful arts organisation that has shown appropriate resilience and fortitude. This company, despite doing incredible work, was defunded in the 2016 funding round by the Australia Council.

It has continued to survive because of the extraordinary effort of its artists and supporters.

Since the introduction of a “competition strategy” mentality in 2016, vital activities and organisations that underpin the arts are being lost, even if they have been essential to the development of a sector for 40 years. And arts activities that are inspirational and unique, such as Slingsby, are not supported.

Authors: Jo Caust, Associate Professor and Principal Fellow (Hon), University of Melbourne