The phoenix factor: what home gardeners can learn from nature's rebirth after fire

- Written by Kingsley Dixon, John Curtin Distinguished Professor, Curtin University

A startling phenomenon occurs after a bushfire tears through a landscape. From the blackened soil springs an extraordinary natural revival – synchronised germination that carpets the landscape in flowers and colour.

So what is it in bushfires that gives plants this kiss of life? The answer is smoke, and it is increasingly transforming everything from large-scale land regeneration to nurseries and home gardening.

The mystery of seed germination

Burnt plants survive bushfires in various ways. Some are protected by woody rootstocks and bark-coated stems; others resprout from underground buds. But most plants awaken their soil seed bank, which may have lain dormant for decades, or even a century.

However, this smoke-induced seed germination is not easily replicated by humans trying to grow the plants themselves. Traditionally, many native Australian flora species – from fringe-lilies to flannel flowers and trigger plants – could not be grown easily or at all from seed.

The fringe-lily, the seed of which has been found to germinate after smoke treatment.

Flickr

The fringe-lily, the seed of which has been found to germinate after smoke treatment.

Flickr

In recent decades this has meant the plants were absent from restoration programs and home gardens, reducing biodiversity.

In 1989, South African botanist and double-PhD Dr Johannes de Lange grappled with a similar conundrum. He was trying to save the critically rare Audonia capitata, which was down to a handful of plants growing around Cape Town. The seed he collected could not be germinated, even after heat and ash treatments from fire. Extinction looked inevitable.

But during a small experimental fire, a wind change enveloped de Langer in thick smoke. With watering eyes, he realised that smoke might be the mysterious phoenix factor that would coax the seeds to life. By 1990 he had shown puffing smoke onto soil germinated his rare species in astonishing numbers.

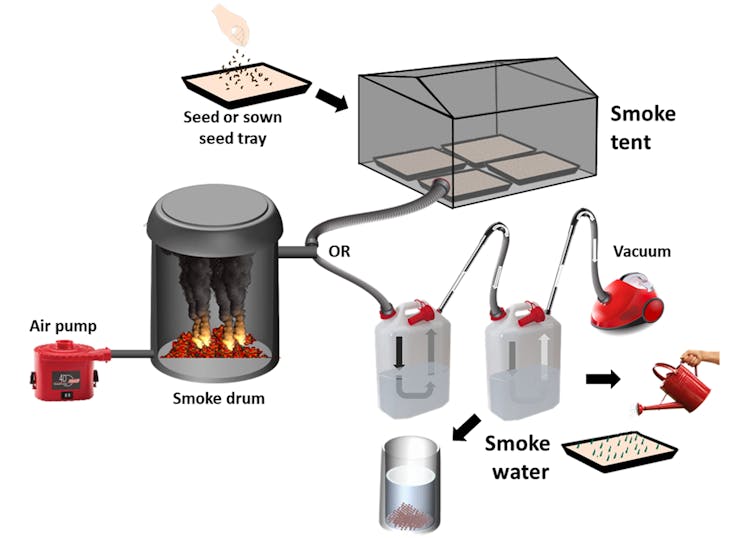

The technique is simple. Create a smouldering fire of dry and green leafy material and pass the smoke into an enclosed area where seed has been sown into seed trays or spread as a thin layer. Leave for one hour and water sparingly for ten days to prevent the smoke from washing out of the seed mix. The rest is up to nature.

Diagram showing the various ways that smoke is applied to seeds.

Supplied by Simone Pedrini

Diagram showing the various ways that smoke is applied to seeds.

Supplied by Simone Pedrini

Taking smoke germination to the world

Soon after the de Lange discovery, I visited the Kirstenbosch National Botanic Garden in Cape Town. I was shown a few trays of seedlings out the back – some from seeds treated with smoke, some without. The difference was stark. Smoke-treated seeds produced a riot of green, compared to others that resulted in sparse, straggling seedlings.

A tray of seedlings where seed was treated with smoke, left, compared to a non-treated tray.

Supplied by author

A tray of seedlings where seed was treated with smoke, left, compared to a non-treated tray.

Supplied by author

But was smoke just an isolated African phenomenon, I wondered? Would 150 years of frustrated efforts to germinate some of Australia’s most spectacular and colourful species – from grevillea and fan-flowers to rare native heaths – also be transformed by smoke?

At first, the answer appeared to be no, as every attempt with Australian wildflower seed failed. But after many trials, which I oversaw as Director of Science at the Western Australian Botanic Garden, success came in 1993. Extra time in the smoke house and a serendipitous failure in the automated watering system resulted in the germination of 25 different species with seedlings. Some were thought to have never been germinated by humans before, such as wild-picked yellow bells (Geleznowia verrucosa) or the giant feather rush (Loxocarya gigas).

Read more: The exquisite blotched butterfly orchid is an airy jewel of the Australian landscape

This discovery meant for the first time smoke could be used for difficult-to-germinate species for the home gardener and cut flower growers. These days more than 400 species of native seeds, and potentially more than 1,000, respond to smoke treatment. They include kangaroo paw, cotton-tails, spinifex, native bush food tomatoes and fragrant boronias.

Highway plantings, mine site restoration and, importantly, efforts to save threatened plant species now also benefit greatly from the smoke germination technique. For example, smoke houses are now a regular part of many nurseries, which also purchase smoke water to soak seeds for sowing later.

Kangaroo paw seeds respond well to smoke treatment.

Supplied by the author

Kangaroo paw seeds respond well to smoke treatment.

Supplied by the author

In mine site restoration, direct application of smoke to seeds dramatically improves germination performance. This translates into multimillion-dollar savings in the cost of seed.

Smoke is also a powerful research tool used to audit native soil seed banks, which includes demonstrating the adverse affects of prescribed burning in winter and spring on native species survival.

Collaboration with research groups in the US, China, Europe and South America has expanded the use of smoke to germinate similarly stubborn seed around the world.

So what is smoke’s secret ingredient?

In 2013, an Australian research team made a breakthrough in determining which of the 4,000 chemicals in a puff of smoke resulted in such starting germination. They patented the chemical and published the discovery in the journal Science.

The smoke chemical, part of the butenolide group of molecules, was named karrikinolide, inspired by the local Indigenous Noongar word for smoke, karrik.

Karrikinolide is no shrinking violet of a molecule: just half a teaspoon is enough to germinate a hectare of bushland, which equates to 20 million seeds.

Read more: How the land recovers from wildfires – an expert's view

Smoke is sold to home gardeners and for commercial use in the form of smoke water, smoke-impregnated disks, or smoke granules. All contain the magical karrikinolide molecule.

Why not try it at home?

Home gardeners can try smoking their own seeds – but what you burn matters. Wood smoke can be toxic to seeds. Making your own smoke from leafy material and dry straw ensures you have the right combustible materials for germination.

At least 400 native seed species, and possibly up to 1,000, have been found to respond to smoke treatment.

Supplied by author

At least 400 native seed species, and possibly up to 1,000, have been found to respond to smoke treatment.

Supplied by author

For the home gardener, having a bottle of smoke water on hand or constructing your own smokehouse can make all the difference to germinating many species – including those stubborn parsley seeds. To find out more, this webinar shows you how to use smoke and even construct your own smoke apparatus.

Authors: Kingsley Dixon, John Curtin Distinguished Professor, Curtin University