5 things to know about the traditional Christian doctrine of hell

- Written by Philip Almond, Emeritus Professor in the History of Religious Thought, The University of Queensland

Martyn Iles, managing director of the Australian Christian Lobby, dodged the question this week when asked by Lisa Wilkinson on The Sunday Project if he believed that homosexuals go to hell. Apparently we are all going there, he suggested, unless we find salvation through Jesus.

The Australian Christian Lobby is now hosting an online crowd-funding appeal for Israel Folau’s legal battle against Rugby Australia, after Folau was sacked over an Instagram post warning that homosexuals will go to hell. It has donated $100,000 to his cause.

Israel Folau in 2018.

Jan Touzeau/EPA

Israel Folau in 2018.

Jan Touzeau/EPA

The churches that belong to the Australian Christian Lobby (mostly Pentecostal and Baptist), along with conservative Catholic and Protestant churches continue to follow the traditional Christian view of hell.

It is not a doctrine for the fainthearted. So what is this hell like? Here are five things about it worth knowing.

Read more: Why the Israel Folau case could set an important precedent for employment law and religious freedom

Most of us are going there

“We’re all doomed!” St. Paul, as Folau has reminded us, believed that homosexuals, the immoral, idolaters, adulterers, thieves, the greedy, drunkards, revilers and robbers would not inherit the Kingdom of God (1 Corinthians 6.9).

Jesus said nothing about homosexuals. But he clearly indicated that most of us enter hell through the wide gate that leads to destruction and few through the narrow gate that leads to life (Matthew 7.13-14). In short, the vast majority are doomed to hell. For centuries, this was the default position for both Catholics and Protestants.

Responding to Wilkinson, Iles said rather blandly that the “mainstream Christian belief on this is that all of us are born going to hell” and we will end up there if “we decline the sacrifice of Jesus Christ on the cross”.

For modern conservative Protestants, while in principle, God has the final say on who is saved and who is damned, the clear expectation is that only those who are “born again” have any sort of a chance.

Eternal torments

In traditional Christian doctrine, hell was conceived as a place, generally beneath the earth, where the wicked would be punished for eternity. There would be both psychological torment – at our knowing we had lost the opportunity for salvation – and physical ones inflicted by the Devil and his demons. There were gnawing worms and unquenchable fires. No escape from hell or mitigation of eternal torment was possible.

God would laugh at the sufferings of the damned, said the English puritan Richard Baxter. “Is it not a terrible thing,” he asked, “to a wretched soul, when it shall lie roaring perpetually … in the flames of Hell, and the God of mercy himself shall laugh at them?”

The judgement

The decision as to whether we went to heaven or hell was made by God at the time of our deaths. (The general judgement of all the resurrected dead on the final Day of Judgement merely confirmed God’s previous one.) As the greatest Catholic theologian Thomas Aquinas rather elegantly put it, “the soul will remain perpetually in whatever last end it is found to have set for itself at the time of death, desiring that state as the most suitable, whether it is good or evil”.

Read more: Friday essay: what might heaven be like?

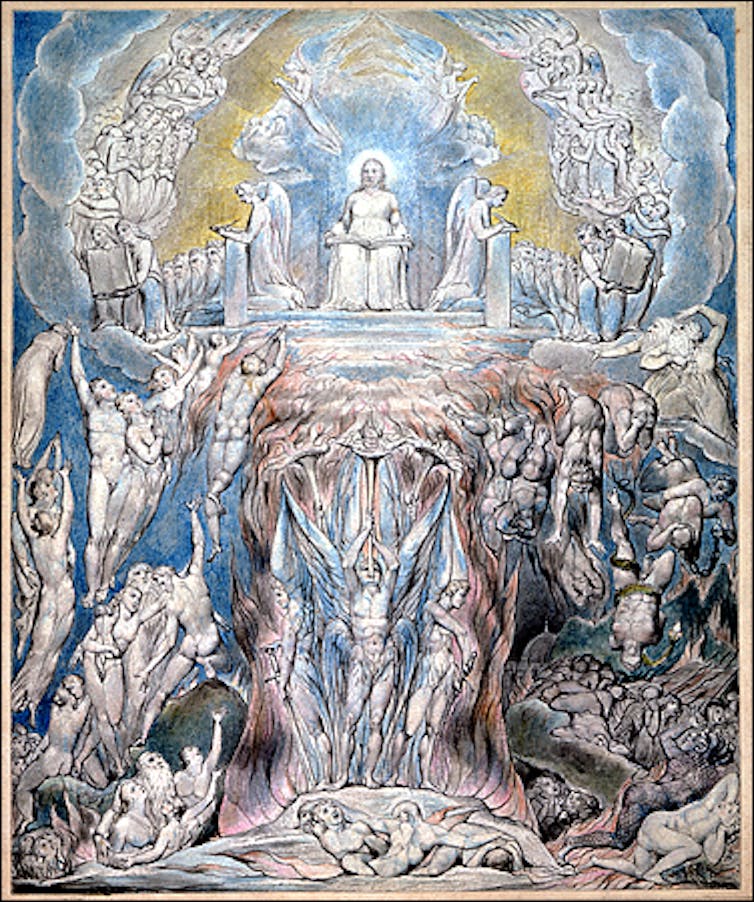

William Blake, The Day of Judgment, 1805.

Wikimedia Commons

William Blake, The Day of Judgment, 1805.

Wikimedia Commons

Still, Christianity has never quite worked out whether heaven or hell is the consequence of righteous or wicked lives, or whether God is completely arbitrary in his decision making about our final destination.

The Australian Christian Lobby, however, follows the conservative Protestant tradition: so infected are we with the original sin of Adam and Eve, we are all doomed to hell from the moment of our birth and only Jesus can save us from it.

Purgatory

Amidst the gloom, there was one bright spot in the traditional Christian doctrine of hell. Our punishment there would be proportionate to our sins just as our rewards in heaven would be proportionate to our virtues.

This sense of proportionality led around the year 1000 CE to the invention of another place between heaven and hell – a place of purification of our sins. It arose from the recognition that while most of us were not sufficiently meritorious to deserve heaven instantly after death, most of us were also not sufficiently wicked to deserve eternal punishment.

Gabriel von Max, Purgatory, circa 1885.

Wikimedia Commons

Gabriel von Max, Purgatory, circa 1885.

Wikimedia Commons

Purgatory was the place where those who were judged worthy of heaven eventually were purged, purified and punished for their sins before going on to their heavenly reward.

Purgatory thus became the default destination after death. Divine justice and mercy were better served by a place where souls, who, like most of us, were not really all that good at being really bad, could be both punished and perfected. Hell then was reserved only for the most incorrigible.

Even so, Purgatory was no holiday resort. The inhabitants were purified by fire. The heat was at times so intense, Dante tells us in his Purgatory, that “I could have flung myself … for coolness, in a vat of boiling glass.”

Purgatory purged

The Protestant reformers of the 16th century hated the idea of Purgatory and threw it out. They saw it as the root cause of corruption within the Church as people paid money on earth to the Church to try to lessen their time there.

Protestant Christianity therefore returned to the harsh either/or of heaven or hell, determined by God at the time of death (or birth). Humanity was again classified into only two classes – the saved and the damned.

Some Protestants from the 17th to 19th centuries attempted to mitigate this harsh idea of hell. Some argued that, after a period of time in hell, all souls would eventually be saved. Others suggested that souls would be annihilated after having done their time of punishment in hell.

By the 20th century, liberal Christians, Protestant and Catholic, were finding it difficult to square away belief in a God of love with the doctrine of eternal torments in the fires of hell. For them, “hell” has been rethought as a state (but no longer a place) of life after death in which we freely choose to stay alienated from God and from which we can eventually be saved if we so wish.

Today’s conservative Christians, however, remain unmoved by the possibility of eventual salvation from hell for everyone. The doctrine of eternal torments in hell has stayed on their theological agenda.

Authors: Philip Almond, Emeritus Professor in the History of Religious Thought, The University of Queensland

Read more http://theconversation.com/5-things-to-know-about-the-traditional-christian-doctrine-of-hell-119380