More fish, more fishing: why strategic marine park placement is a win-win

- Written by Kerstin Jantke, Postdoctoral Researcher on conservation biology, University of Hamburg

Australia has some of the most spectacular marine ecosystems on the planet – including, of course, the world-famous Great Barrier Reef. Many of these places are safe in protected areas, and support a myriad of leisure activities such as recreational fishing, diving and surfing. No wonder eight in ten Aussies live near the beach.

Yet threats to marine ecosystems are becoming more intense and widespread the world over. New maps show that only 13% of the oceans are still truly wild. Industrial fishing now covers an area four times that of agriculture, including the farthest reaches of international waters. Marine protected areas that restrict harmful activities are some of the last places where marine species can escape. They also support healthy fisheries and increase the ability of coral reefs to resist bleaching.

Read more: Most recreational fishers in Australia support marine sanctuaries

One hundred and ninety-six nations, including Australia, agreed to international conservation targets under the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. One target calls for nations to protect at least 10% of the world’s oceans. An important but often overlooked aspect of this target is the requirement to protect a portion of each of Earth’s unique marine ecosystems.

How are we tracking?

The world is on course to achieve the 10% target by 2020, with more than 7.5% of the ocean already protected. However, our research shows that many marine protected areas are located poorly, leaving many ecosystems underprotected or not protected at all.

What’s more, this inefficient placement of marine parks has an unnecessary impact on fishers. While marine reserves typically improve fisheries’ profitability in the long run, they need to be placed in the most effective locations.

We found that since 1982, the year nations first agreed on international conservation targets, an area of the ocean almost three times the size of Australia has been designated as protected areas in national waters. This is an impressive 20-fold increase on the amount of protection that was in place beforehand.

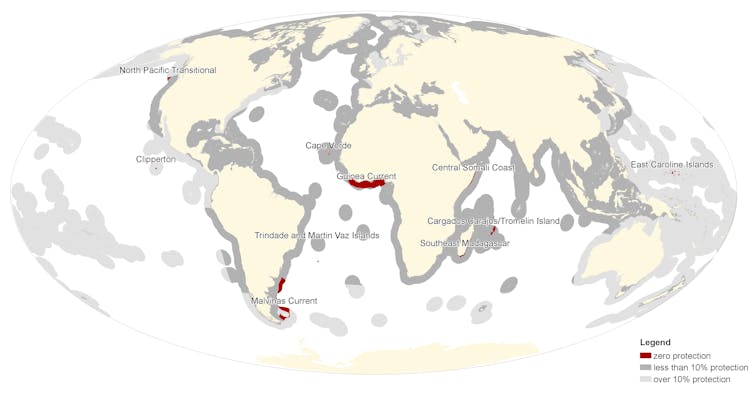

But when we looked at specific marine ecosystems, we found that half of them fall short of the target level of protection, and that ten ecosystems are entirely unprotected. For example, the Guinea Current off the tropical West African coast has no marine protected areas, and thus nowhere for its wildlife to exist free from human pressure. Other unprotected ecosystems include the Malvinas Current off the southeast coast of South America, Southeast Madagascar, and the North Pacific Transitional off Canada’s west coast.

Marine park coverage of global ecosystems. Light grey: more than 10% protection; dark grey: less than 10% protection; red: zero protection.

Author provided

Marine park coverage of global ecosystems. Light grey: more than 10% protection; dark grey: less than 10% protection; red: zero protection.

Author provided

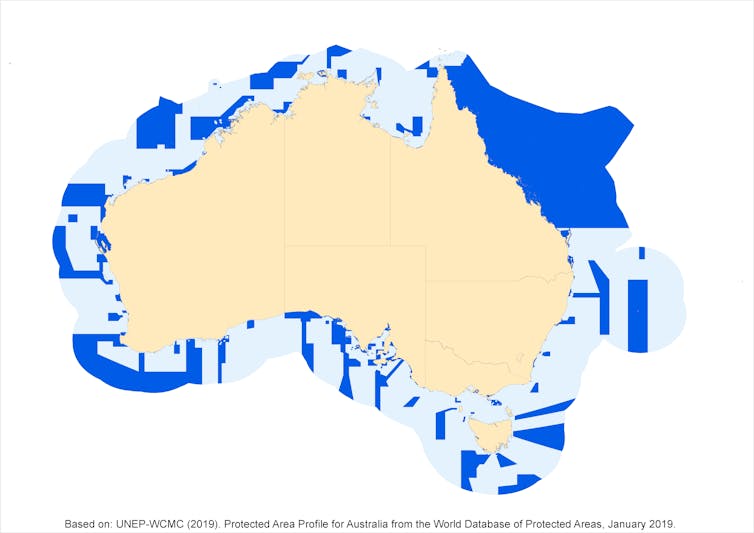

Australia performs comparatively well, with more than 3 million square km of marine reserves covering 41% of its national waters. Australia’s Coral Sea Marine Park is one of the largest marine protected areas in the world, at 1 million km². However, a recent study by our research group found that several unique ecosystems in Australia’s northern and eastern waters are lacking protection.

Furthermore, the federal government’s plan to halve the area of strict “no-take” protection inside marine parks does not bode well for the future.

How much better can we do?

To assess the scope for improvement to the world’s marine parks, we predicted how the protected area network could have been expanded from 1982.

With a bit more strategic planning since 1982, the world would only need to conserve 10% of national waters to protect all marine ecosystems at the 10% level. If we had planned strategically from as recently as 2011, we would only need to conserve 13% of national waters. If we plan strategically from now on, we will need to protect more than 16% of national waters.

If nations had planned strategically since 1982, the world’s marine protected area network could be a third smaller than today, cost half as much, and still meet the international target of protecting 10% of every ecosystem. In other words, we could have much more comprehensive and less costly marine protection today if planning had been more strategic over the past few decades.

The lack of strategic planning in previous marine park expansions is a lost opportunity for conservation. We could have met international conservation targets long ago, with far lower costs to people - measured in terms of a short-term loss of fishing catch inside new protected areas.

This is not to discount the progress made in marine conservation over the past three decades. The massive increase of marine protected areas, from a few sites in 1982, to more than 3 million km² today, is one of Australia’s greatest conservation success stories. However, it is important to recognise where we could have done better, so we can improve in the future.

Australia’s marine park network.

Author provided

Australia’s marine park network.

Author provided

This is also not to discount protected areas. They are important but can be placed better. Furthermore, long-term increases in fish populations often outweigh the short-term cost to fisheries of no-take protected areas.

Two steps to get back on track

In 2020, nations will negotiate new conservation targets for 2020-30 at a UN summit in China. Targets are expected to increase above the current 10% of every nation’s marine area.

We urge governments to rigorously assess their progress towards conservation targets so far. When the targets increase, we suggest they take a tactical approach from the outset. This will deliver better outcomes for nature conservation, and have less short-term impact on the fishing industry.

Read more: More than 1,200 scientists urge rethink on Australia's marine park plans

Strategic planning is only one prerequisite for marine protected areas to effectively protect unique and threatened species, habitats and ecosystems. Governments also need to ensure protected areas are well funded and properly managed.

These steps will give protected areas the best shot at halting the threats driving species to extinction and ecosystems to collapse. It also means these incredible places will remain available for us and future generations to enjoy.

Authors: Kerstin Jantke, Postdoctoral Researcher on conservation biology, University of Hamburg