Expect tax cuts and an emptying of the cupboards in a budget cleanout as the billions roll in

- Written by Warren Hogan, Industry Professor, University of Technology Sydney

It has been just over three months since the December budget update but once again the government has been gifted a windfall of unexpected revenues, despite a raft of economic data suggesting the economy has slowed its rate of growth.

This is because the things that really matter to the budget have all done better than was expected by the Treasury just months ago. Strong conditions in commodity markets and lower unemployment mean that in the current financial year the budget bottom line will be about A$3 billion better than had been expected in December, and about A$12 billion better next financial year.

Since the last budget only last May, the outlook for 2018-19 has improved by A$12.3 billion and the outlook for 2019-20 by $13.8 billion.

Going up

Rising commodity prices and export volumes have pushed up the profits and tax bills of mining companies.

Iron ore is the standout. Prices have exceeded the Treasury’s December forecast on the back of lower international supply (a result of the tragic dam wall collapse in Brazil) and continued growth in demand from China.

In December, Treasury expected iron ore prices to average US$55 a tonne. But in fact they have averaged about US$75 a tonne. That alone will add about A$2 billion to government revenues in 2018-19 and, if maintained, A$6 billion in 2019-20.

Add in a weaker Australian dollar and the combined effect will account for almost half of the net improvement in the overall budget position this financial year and the next.

Iron ore is only one of our exports.

Coal prices have also exceeded expectations, which should add another A$1 billion to A$1.5 billion to revenue over the next two years.

Read more: An evening with the treasurer: how governments belt out budget hits and hope someone is listening

And there’s more to it than mining. Corporate profits have generally been strong despite some storm clouds forming around the banking industry and the economy more generally.

Another thing driving the better budget starting point is strong jobs growth and a lower than expected unemployment rate, boosting the government’s financial position through lower unemployment benefits and a higher personal tax take. The February employment statistics showed an unemployment rate of 4.9%.

The Treasury had expected the rate to fall more slowly, only getting to 5% by June and then staying there for several years.

If the budget cupboard was untouched, which it won’t be, the budget would have a deficit of next to nothing this financial year and an impressive surplus as high as 1% of gross domestic product next year, a year ahead of the government’s schedule.

But it mightn’t last

These upside surprises from the corporate tax take can just as quickly go the other way.

Assuming they will last, as budgets often do, would be to make the same mistake as the Howard-Costello government, which made permanent changes to tax rates and commitments on the back of revenue that prove to be temporary. So did the Gillard-Swan government some years later with its “spreading the benefits of the boom” package.

Corporate profits might struggle to improve in future years in an increasingly difficult economic environment. No one knows what will happen with commodity prices. Right now China is using infrastructure spending to stimulate its economy, but it won’t always do that. Eventually its growth will be less metal-intensive.

But with the government well behind in the polls, I doubt these considerations are getting much attention.

China drives budgets, the US drives rates

The US economy sets the global price of money, which in turn determines the environment in which our Reserve Bank sets Australian interest rates and works out how to deal with the bursting of the housing bubble, which was itself in no small part the result of an easy US monetary policy in the wake of the global financial crisis.

China, on the other hand, determines the global price of commodities and trade flows and so helps determine corporate profitability in Australia.

This contrast between the two has never been greater, with the government flush with unexpected revenues while the Reserve Bank walks a knife-edge of low real economic growth, financial stability risks, and already easy monetary policy.

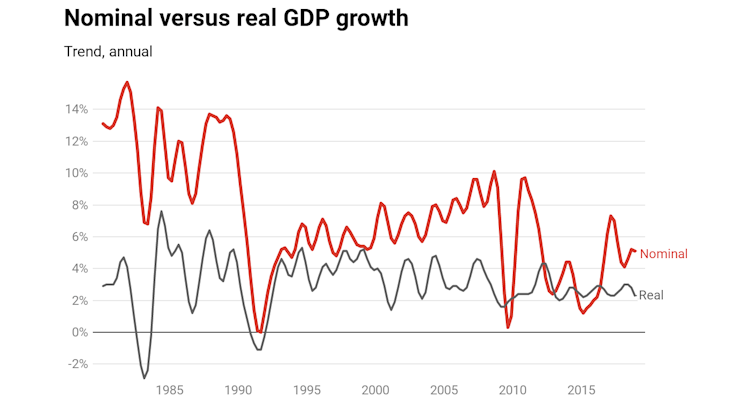

It is best summed up in this chart of real and nominal gross domestic product, which shows annual growth in real GDP (which affects the economy) slowing to 2.3% while growth in nominal GDP (which drives the dollars flowing into the Treasury) growth climbing to more than 5%.

ABS National Accounts

Looking beyond this budget, the major risk for the Australian economy is a retrenchment of consumer spending on the back of falling house prices and tighter credit conditions.

The national accounts suggest it has already started.

The worry is that domestic spending, which is dominated by consumer spending, will weaken to the point at which it forces businesses to shelve hiring and investment plans, pushing unemployment back up.

A vicious cycle could result in some type of recession.

How can the government and the Reserve Bank try to control these risks?

One way would be to do what they have always done and cut interest rates in an attempt to boost household and business cash flows.

Read more:

Now is the time to plan how to fight the next recession

Another would be to take some of the free cash being generated by China and use it to boost domestic demand through temporary arrangements that help the economy ride out the adjustment to lower house prices.

It could be done in many forms including tax cuts and targeted cash injections into low and middle income households.

Expect extra and earlier tax cuts

The government has known about the much better revenue position for months.

To date it has displayed incredible restraint in spending it.

New policy announcements since the December update have been limited to about A$500 billion a year, which isn’t bad for a government facing an election wipeout before winter.

But it would be wise not to get too glowing about its restraint.

Instead we should expect a cascade of policy announcements culminating in a major tax cut to be revealed on budget night next Tuesday.

The government has a A$12 billion war chest.

It is most likely to spend it in the form of tax cuts, most likely by bringing forward the second stage of the already announced cuts due to take effect in July 2022.

Read more:

Grattan on Friday: Josh Frydenberg has a great job at the worst time

That would mean lifting the ceiling for the 32.5% tax rate from A$90,000 to A$120,000 and lifting the ceiling for the 19% rate from A$37,000 to A$41,000.

Bringing forward those already legislated tax cuts by three years to July 2019 would cost the budget less than A$10 billion a year and still leave room for a surplus in 2019-20 and room for targeted election pork barrelling.

With the government so far behind in the polls there is virtually zero chance this extra income will be saved for a rainy day. Although the Coalition’s chances of re-election are remote, Prime Minister Scott Morrison is an optimist who might think a surge of generosity and a few lucky breaks could get him over the line.

The more likely possibility of an election loss means Morrison will want to keep the incoming government’s cupboard as bare as he can. This means keeping the budget surpluses small so that if the Labor Party wants to go on a spending spree, it will have to renege on his promised tax cuts.

Read more:

No surplus, no share market growth, no lift in wage growth. Economic survey points to bleaker times post-election

The good news is that whatever the government does in the budget and no matter what party forms the next government, the budget position is all but back in balance.

It will hold us in good stead should the global economy run into trouble.

It will be all the more needed if the Reserve Bank pushes interest rates below 1% over the coming year, leaving it little room to cut further.

ABS National Accounts

Looking beyond this budget, the major risk for the Australian economy is a retrenchment of consumer spending on the back of falling house prices and tighter credit conditions.

The national accounts suggest it has already started.

The worry is that domestic spending, which is dominated by consumer spending, will weaken to the point at which it forces businesses to shelve hiring and investment plans, pushing unemployment back up.

A vicious cycle could result in some type of recession.

How can the government and the Reserve Bank try to control these risks?

One way would be to do what they have always done and cut interest rates in an attempt to boost household and business cash flows.

Read more:

Now is the time to plan how to fight the next recession

Another would be to take some of the free cash being generated by China and use it to boost domestic demand through temporary arrangements that help the economy ride out the adjustment to lower house prices.

It could be done in many forms including tax cuts and targeted cash injections into low and middle income households.

Expect extra and earlier tax cuts

The government has known about the much better revenue position for months.

To date it has displayed incredible restraint in spending it.

New policy announcements since the December update have been limited to about A$500 billion a year, which isn’t bad for a government facing an election wipeout before winter.

But it would be wise not to get too glowing about its restraint.

Instead we should expect a cascade of policy announcements culminating in a major tax cut to be revealed on budget night next Tuesday.

The government has a A$12 billion war chest.

It is most likely to spend it in the form of tax cuts, most likely by bringing forward the second stage of the already announced cuts due to take effect in July 2022.

Read more:

Grattan on Friday: Josh Frydenberg has a great job at the worst time

That would mean lifting the ceiling for the 32.5% tax rate from A$90,000 to A$120,000 and lifting the ceiling for the 19% rate from A$37,000 to A$41,000.

Bringing forward those already legislated tax cuts by three years to July 2019 would cost the budget less than A$10 billion a year and still leave room for a surplus in 2019-20 and room for targeted election pork barrelling.

With the government so far behind in the polls there is virtually zero chance this extra income will be saved for a rainy day. Although the Coalition’s chances of re-election are remote, Prime Minister Scott Morrison is an optimist who might think a surge of generosity and a few lucky breaks could get him over the line.

The more likely possibility of an election loss means Morrison will want to keep the incoming government’s cupboard as bare as he can. This means keeping the budget surpluses small so that if the Labor Party wants to go on a spending spree, it will have to renege on his promised tax cuts.

Read more:

No surplus, no share market growth, no lift in wage growth. Economic survey points to bleaker times post-election

The good news is that whatever the government does in the budget and no matter what party forms the next government, the budget position is all but back in balance.

It will hold us in good stead should the global economy run into trouble.

It will be all the more needed if the Reserve Bank pushes interest rates below 1% over the coming year, leaving it little room to cut further.

Authors: Warren Hogan, Industry Professor, University of Technology Sydney