Before epidemiologists began modelling disease, it was the job of astrologers

- Written by Michelle Pfeffer, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in History, The University of Queensland

The internet is awash with comparisons between life during COVID-19 and life during the Bubonic plague. The two have many similarities, from the spread of misinformation and the tracking of mortality figures, to the ubiquity of the question “when will it end?”

But there are, of course, crucial differences between the two. Today, when looking for information on the incidence, distribution, and likely outcome of the pandemic, we turn to epidemiologists and infectious disease models. During the Bubonic plague, people turned to astrologers.

Exploring the role played by astrologers in past epidemics reminds us that although astrology has been debunked, it was integral to the development of medicine and public health.

The flu, written in the stars

Before germ theory, the Scientific Revolution and then the Age of Enlightenment, it was common for medical practitioners to use astrological techniques in their everyday practice.

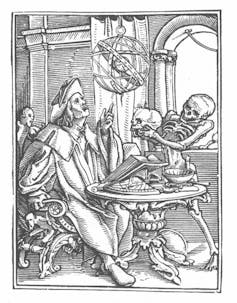

Hans Holbein’s Danse Macabre woodcut (1523-25).

Wikimedia

Hans Holbein’s Danse Macabre woodcut (1523-25).

Wikimedia

Compared to the simplistic horoscopes in today’s magazines, premodern astrology was a complex field based on detailed astronomical calculations. Astrologers were respected health authorities who were taught at the finest universities throughout Europe, and hired to treat princes and dukes.

Astrology provided physicians with a naturalistic explanation for the onset and course of disease. They believed the movements of the celestial bodies, in relation to each other and the signs of the Zodiac, governed events on earth. Horoscopes mapped the heavens, allowing physicians to draw conclusions about the onset, severity, and duration of illness.

The impact of astrology on the history of medicine can still be seen today. The term “influenza” was derived from the idea that respiratory disease was a product of the influence of the stars.

Read more: Altered mind this morning? Hehe, just blame the planets

Public health and plague

Astrologers were seen as important authorities for the health of communities as well as individuals. They offered public health advice in annual almanacs, which were some of the most widely read literature in the premodern world.

Almanacs provided readers with tables for astrological events for the coming year, as well as advice on farming, political events, and the weather.

The publications were also important disseminators of medical knowledge. They explained basic medical principles and suggested remedies. They made prognostications about national health, using astrology to predict when an influx of venereal disease or plague was likely to arise.

These public health predictions were often based on the astrological theory of conjunctions. According to this theory, when certain planets seem to approach each other in the sky from our perspective on earth, great socio-cultural events are bound to occur.

When Bubonic plague hit France in 1348, the King asked the physicians at the University of Paris to account for its origins. Their answer was that the plague was caused by a conjunction of Saturn, Mars, and Jupiter.

Read more: How medieval writers struggled to make sense of the Black Death

Predictions from above

Astrological accounts of plague remained popular into the 17th century. In this period, astrology was increasingly attacked as superstitious, so some astrologers tried to set their field on a more scientific grounding.

In an effort to make astrology more scientific, the English astrologer John Gadbury produced one of the earliest epidemiological studies of disease.

In London’s Deliverance Predicted (1655), Gadbury claimed his contemporaries couldn’t explain when plagues would arrive, or how long they’d last.

Gadbury proposed that if planets caused plagues, then planets also stopped plagues. Studying astrological events would therefore allow one to predict the course of an epidemic.

He gathered data from the previous four great London plagues (in 1593, 1603, 1625, and 1636), scouring the Bills of Mortality for weekly plague death rates, and compiling A Table shewing the Increase and Abatement of the Plague. Gadbury also used planetary tables to locate the planets’ positions throughout the epidemics. He then compared his data sets, looking for correlations.

Gadbury found a correlation between intensity of plague and the positions of Mars and Venus. Plague deaths increased sharply in July 1593, at which point Mars had moved into an astrologically significant position. Deaths then abated in September, when Venus’s position became more significant. Gadbury concluded that the movement of “the fiery Planet Mars” was the origin of pestilence and the “cause of its raging”, while the influence of the “friendly” Venus helped abate it.

Gadbury then applied his findings to the pestilence plaguing London at the time. He was able to correlate the beginnings of the plague in late 1664 and its growing intensity in June 1665 with recent astrological events.

He predicted the upcoming movement of Venus in August would see a fall in plague deaths. Then the movement of Mars in September would make the plague deadlier, but the movements of Venus in October, November, and December would halt the death rate.

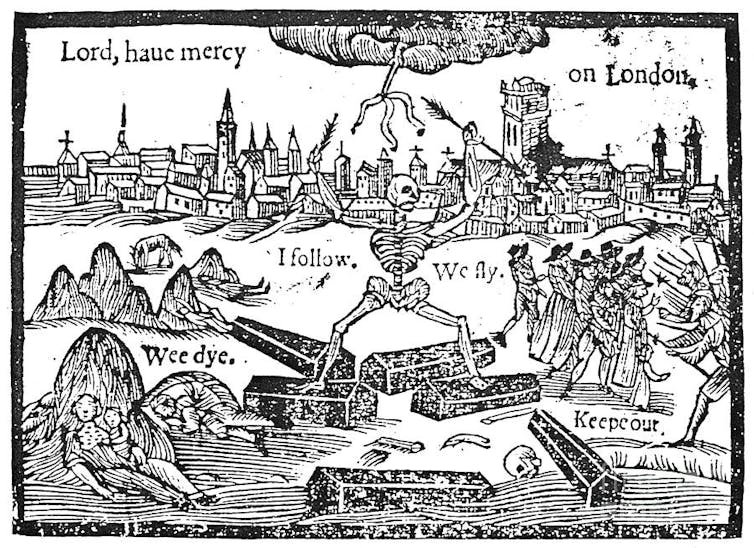

The black death in London, circa 1665. Creator unknown.

The black death in London

The black death in London, circa 1665. Creator unknown.

The black death in London

Looking for patterns

Unfortunately for Gadbury, plague deaths increased dramatically in August. However, he was right in predicting a peak in September followed by a steep decrease at the end of the year. If Gadbury had accounted for other correlates – such as the coming of winter – his study might have been received more favourably.

The medical advice in Gadbury’s book certainly doesn’t stand up today. He argued the plague was not contagious, and that isolating at home only caused more deaths. Yet his attempt to find correlations with fluctuating mortality rates offers an early example of what we now call epidemiology.

While we may discredit Gadbury’s astrological assumptions, examples such as this illustrate the important role astrology played in the history of medicine, paving the way for naturalist explanations of infectious disease.

Authors: Michelle Pfeffer, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in History, The University of Queensland