how history might read Morrison's coronavirus leadership

- Written by Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

What does political leadership look like in a pandemic?

Many of us probably carry images in our heads of what good leadership might be in a depression or a war. But before 2020 few of us would have had any conception of what political leadership might look like during a life-threatening public health crisis.

We took from last summer some fairly firm ideas of what leadership in a bushfire crisis should not look like. Political leaders should not leave for luxurious overseas holidays. They should not expect those who fear for their lives and property to find inspiration in the exploits of the Australian cricket team. They should not force themselves onto traumatised people when offering nothing except the chance to participate in a photo opportunity. They should not run party-political advertisements that seek to obscure their own monumental failures.

Read more: How Australia's response to the Spanish flu of 1919 sounds warnings on dealing with coronavirus

Charles II: good in a crisis.

Royal Museums Greenwich

Charles II: good in a crisis.

Royal Museums Greenwich

Above all, they should not announce that it’s not their job to hold the hose. As it happens, we already had a famous model of what a national leader might do in a fire.

In 1666, King Charles II of England was widely regarded as a worthless playboy with nothing much to his credit. In 1665, London lost tens of thousands of people in the Great Plague and there was little that he, or anyone else, had been able to do about it. When a fire broke out in Pudding Lane in the following year, few had any reason to expect Charles would distinguish himself. But his leadership in that fire is famous. It was brave, inspiring and, yes, although he did not hold the hose, he did pass the buckets.

Crises can make leaders but they can also break them – or, as happened over the summer with Morrison, nearly break them. In a recent book, labour historian Liam Byrne explores the early lives and careers of two Labor prime ministers, James Scullin and John Curtin. Each was a product of the Victorian labour movement. Each had regarded himself as a socialist. Each would face a massive national crisis on becoming prime minister that required them to put aside the beliefs of a lifetime.

Scullin faced the Great Depression of the 1930s. He emerged from a brief time in government at the beginning of 1932 damaged and bewildered. The crisis was the breaking and not the making of him. To be fair, it’s hard to imagine how, given the state of the Australian economy and the scale of the problem he faced, anyone could have done much better.

When Australian prime ministers are ranked, Scullin usually occupies a lowly place while Curtin often comes out on top. The success of Curtin’s wartime leadership wasn’t predictable. He was a anti-conscriptionist during the first world war who saw that war as a scheme devised by capitalists to divide and conquer the working class. He was moody, aloof and a worrier. But the crisis of the Pacific War was the making of Curtin as a leader, even if he would not live to see the peace.

We should not exaggerate the extent to which Australians fell in behind Curtin’s urgings. In the present crisis, I’ve occasionally been reminded, during some of Morrison’s occasionally hectoring and patronising performances, of the difficulties Curtin faced.

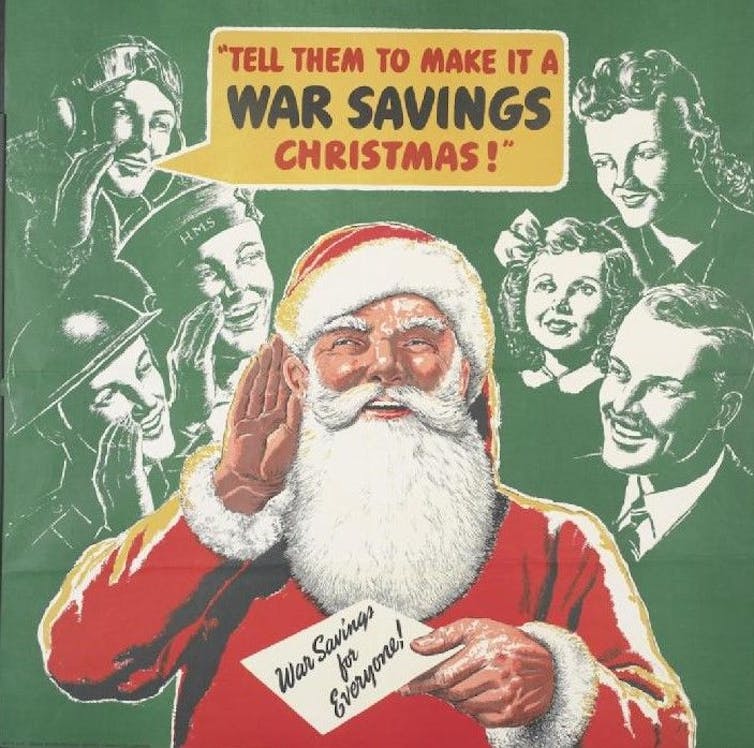

Morrison called panic-buying “un-Australian”, but it must be sufficiently Australian also to have occurred during the war, when people got wind of the approach of clothing rationing. Morrison’s infantilising “early mark” made some bristle in the same way, inevitably, as grown-ups came to resent petty government restrictions during the second world war. The minister in charge of rationing, John Dedman, was famously lampooned for having banned pink icing on wedding cakes and for killing Santa Claus with his restrictions on Christmas advertising. Even in war, adults expect to be treated as adults.

A poster from 1942.

Queensland Museum

A poster from 1942.

Queensland Museum

Morrison could not afford another leadership failure when coronavirus hit. My own view of his leadership by the end of the last summer is that it was badly damaged but unlikely to be terminal. He had already shown himself as an adaptable politician and I expected he would also enjoy the help of a friendly right-wing media in repairing it.

Malcolm Turnbull’s memoir presents a hostile but mainly persuasive account of Morrison as a politician. Turnbull presents him as sneaky and duplicitous. But more importantly, in making sense of his recent leadership, Morrison is painted as a pragmatic political professional unattached to ideology and quite prepared to pick up and drop policies according to his perception of the needs – including his own – in any context.

Read more: Grattan on Friday: Descending the COVID mountain could be hazardous for Scott Morrison

For Morrison, the science on climate change is negotiable, but the science on coronavirus is the last word. He is the kind of leader who is off to the footy one moment and everyone else should also get out and about, then that he’s not and everyone must stay home. He can dismiss the need for a wage subsidy one week and then announce a A$130 billion package the next. He can double the JobSeeker allowance after having for years staunchly opposed even a minor increase as an affront to self-reliance and an intolerable incentive to the unemployed to stay that way.

Morrison can do all of this with very few backward glances and then – if it suits his purposes and he can get away with it – reverse the lot when that suits him as well.

So there is Morrison’s adaptability. But there is also a helpful conservative media. Here, Morrison is not just a nimble leader with a well-developed survival instinct. He is positively Churchillian.

Greg Sheridan of The Australian was early out of the blocks near the end of March. “Scott Morrison could become Australia’s most important war-time leader,” he declared. “If he succeeds, he will join a pantheon which at the moment consists only of John Curtin, a leader who got us through, who worried us through, our last existential challenge.”

More recently, Sheridan’s colleague, Paul Kelly, has extended this to an attack on state premiers as “laggards”. He asked rhetorically whether they were “free riders on the Morrison government and the banks, who keep the economy alive at such dire cost”.

A prime minister who can rely on such free promotion has good reason to expect a bright political future. And Labor Party figures are entitled to ask if they could have expected such generosity in the context of draconian restrictions on personal freedom and massive spending aimed at propping up the economy and saving lives.

As we return to something like political business as usual, Morrison is likely to be subjected to efforts to make him and his government accountable that he has long shown he regards as onerous. How he deals with those, and with the immense challenges of rebuilding the economy in the context of debt, deficit, global depression and the danger of new outbreaks of disease, may well be a more testing challenge to his leadership than anything so far.

Authors: Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University