how the climate impact of beef compares with plant-based alternatives

- Written by Alexandra Macmillan, Associate Professor Environment and Health, University of Otago

Climate Explained is a collaboration between The Conversation, Stuff and the New Zealand Science Media Centre to answer your questions about climate change.

If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, please send it to climate.change@stuff.co.nz

I am wondering about the climate impact of vegan meat versus beef. How does a highly processed patty compare to butchered beef? How does agriculture of soy (if this is the ingredient) compare to grazing of beef?

Both Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat, two of the biggest players in the rapidly expanding meat alternatives market, claim their vegan burger patties (made primarily from a variety of plant proteins and oils) are 90% less climate polluting than a typical beef patty produced in the United States.

The lifecycle assessments underpinning these findings were funded by the companies themselves, but the results make sense in the context of international research, which has repeatedly shown plant foods are significantly less environmentally damaging than animal foods.

It is worth asking what these findings would look like if the impacts of plant-based meats had been compared with a beef patty produced from a grass-fed cattle farm, as is the case in New Zealand, instead of an industrialised feedlot operation that is commonplace in the United States.

Read more: Climate explained: will we be less healthy because of climate change?

A New Zealand perspective

Building on international research mainly carried out in the Northern Hemisphere, we recently completed a full assessment of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with different foods and dietary patterns in New Zealand.

Despite dominant narratives about the efficiency of New Zealand’s livestock production systems, we found the stark contrast between climate impacts of plant and animal foods is as relevant in New Zealand as it is elsewhere.

For example, we found 1 kilogram of beef purchased at the supermarket produces 14 times the emissions of whole, protein-rich plant foods like lentils, beans and chickpeas. Even the most emissions-intensive plant foods, such as rice, are still more than four times more climate-friendly than beef.

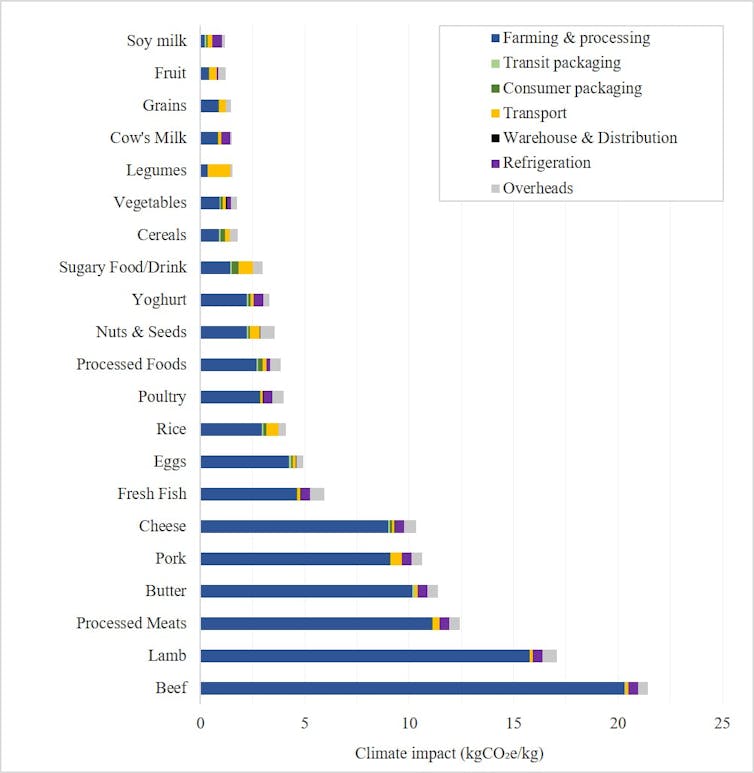

The New Zealand food emissions database: comparing the climate impact of commonly consumed food items in New Zealand.

Drew et al., 2020

The New Zealand food emissions database: comparing the climate impact of commonly consumed food items in New Zealand.

Drew et al., 2020

The climate impact of different foods is largely determined by the on-farm stage of production. Other lifecycle stages such as processing, packaging and transportation play a much smaller role.

Raising beef cattle, regardless of the production system, releases large quantities of methane as the animals belch the gas while they chew the cud. Nitrous oxide released from fertilisers and manure is another potent greenhouse gas that drives up beef’s overall climate footprint.

Climate impact of the New Zealand diet

Everyday food choices can make a difference to the overall climate impact of our diet. In our modelling of different eating patterns, we found every step New Zealand adults take towards eating a more plant-based diet results in lower emissions, better population health and reduced healthcare costs.

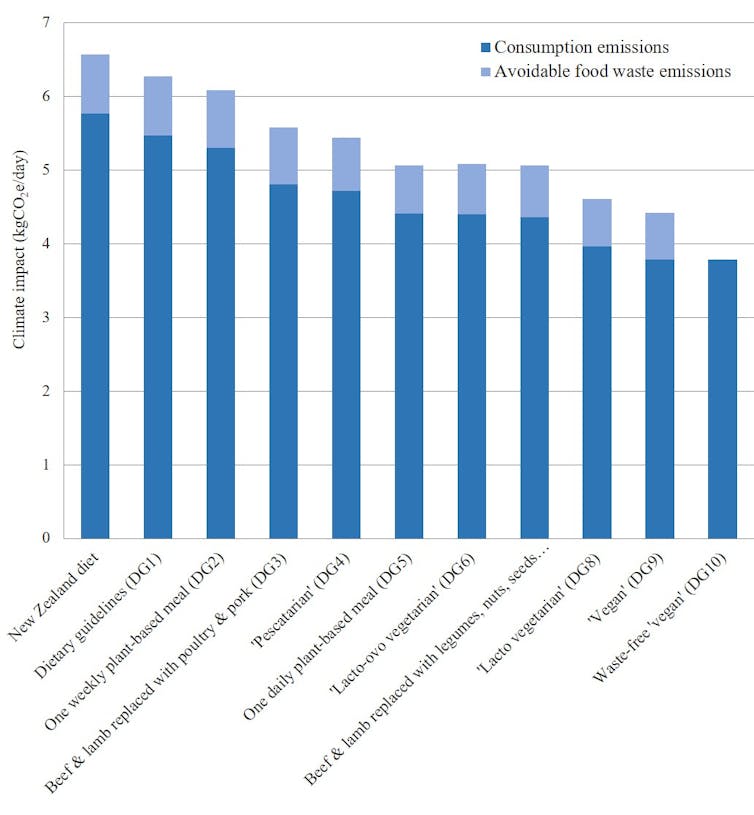

Climate impact of different dietary scenarios, as compared with the typical New Zealand diet.

Drew et al., 2020

Climate impact of different dietary scenarios, as compared with the typical New Zealand diet.

Drew et al., 2020

The graph above shows a range of dietary changes, which gradually replace animal-based and highly processed foods with plant-based alternatives. If all New Zealand adults were to adopt a vegan diet with no food wastage, we estimated diet-related emissions could be reduced by 42% and healthcare costs could drop by NZ$20 billion over the lifetime of the current New Zealand population.

Read more: A vegan meat revolution is coming to global fast food chains – and it could help save the planet

Redesigning the food system

The current global food system is wreaking havoc on both human and planetary health. Our work adds to an already strong body of international research that shows less harmful alternatives are possible.

As pressure mounts on governments around the world to help redesign our food systems, policymakers continue to show reluctance when it comes to supporting a transition toward plant-based diets.

Such inaction appears, in large part, to be driven by the propagation of deliberate misinformation by powerful food industry groups, which not only confuses consumers but undermines the development of healthy and sustainable public policy.

To address the multiple urgent environmental health issues we face, a shift towards a plant-based diet is something many individuals can do for their and the planet’s health, while also pressing for the organisational and policy changes needed to make such a shift affordable and accessible for everyone.

Authors: Alexandra Macmillan, Associate Professor Environment and Health, University of Otago