how Captain Cook blundered his first impression with Indigenous people

- Written by Maria Nugent, Co-Director, Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Australian National University

Captain James Cook arrived in the Pacific 250 years ago, triggering British colonisation of the region. We’re asking researchers to reflect on what happened and how it shapes us today. You can see other stories in the series here and an interactive here.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

In 1970, the bicentenary of the Endeavour’s voyage along the east coast of Australia contributed to a renaissance of storytelling about Captain James Cook.

While government-sponsored commemorations celebrated Cook as an Enlightenment explorer and national founder, Aboriginal people provided their own viewpoints on Cook and his legacy.

During this commemorative period, Indigenous stories about Cook were recorded in the Kimberley region, Arnhem Land and the Wave Hill region in the Northern Territory, along with places on the Queensland coast.

Coinciding with an emerging national movement for Indigenous land rights, these renditions of Cook provided radically different accounts of colonisation and its enduring structures and effects.

These stories questioned the settler mythologising that rendered Cook’s actions as heroic, benign or of historical interest only. And they politicised in unprecedented ways the figure of Cook and the longstanding traditions around the ways Australians remember and celebrate him.

In time, these alternative accounts transformed the ways we understand Cook in Australia – both his own time here in 1770, as well as the cultural production of him as a historical figure in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Captain Cook’s Landing Place Park.

Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

Captain Cook’s Landing Place Park.

Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

The stories told by Hobbles Danaiyarri

Deborah Bird Rose.

Wikipedia

Deborah Bird Rose.

Wikipedia

I began thinking quite differently about my own research on Cook’s encounters at Botany Bay in 1770 after reading the stories told by Hobbles Danaiyarri, a senior Aboriginal lawman and knowledge holder, to the ethnographer Deborah Bird Rose.

Danaiyarri considered Bird Rose a consummate listener, faithful recorder, intelligent interlocutor, incisive interpreter and generous executor. And as Bird Rose later recounted, almost from the moment she arrived to do anthropological fieldwork at Yarralin in the Northern Territory in 1980,

Hobbles had been telling me about Captain Cook and the hidden history of the north.

For nearly three decades, she wrote about the gifts of knowledge – and ways of knowing – he shared with her. Danaiyarri’s spoken-word poetic history – which focused quite extensively on Cook – is one of the great pieces of Australian literature, yet it is still not as widely known as it should be.

The power of a greeting

There’s one section in Danaiyarri’s epic narrative – or saga, as Bird Rose calls it – in which he describes Cook’s failure to say “hello” to the people whose territory he had entered on the east coast. He explains:

[Cook] should have asked him – one of these boss for Sydney – Aboriginal people. People were up there, Aboriginal people. He should have come up and: ‘hello’, you know, ‘hello’. Now, asking him for his place, to come through, because [it’s] Aboriginal land. Because Captain Cook didn’t give him a fair go – to tell him ‘good day’, or ‘hello’, you know.

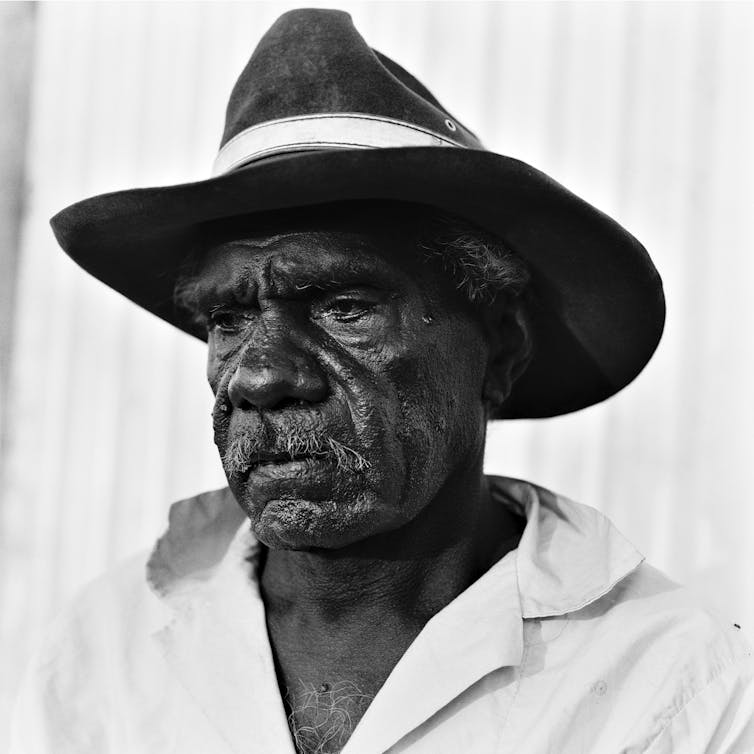

Portrait of Hobbles Danayarri 1980, from the book Balls and Bulldust.

Håkan Ludwigson

Portrait of Hobbles Danayarri 1980, from the book Balls and Bulldust.

Håkan Ludwigson

This sharp accusation that Cook’s monumental failing during his initial trespass into Aboriginal territory was “not saying hello” – rather than, for instance, opening fire – draws attention to the social and cultural expectations, values and dynamics that should have governed such an event.

Danaiyarri’s account peeled back the curtain to show us how this first encounter might have looked from “the other side of the beach”.

Until this time, such critical Indigenous knowledge had not penetrated the vast amount of settler storytelling devoted to Cook’s first landing on the shores of Botany Bay.

The stories we inherited of this episode had cast the Aboriginal people Cook encountered as either ferocious warriors or pathetic cowards. They were not properly seen as bosses for the country, who would expect a stranger to recognise them in that way and act accordingly.

Without acknowledgement of that fundamental principle, our interpretations of Cook’s landing were lacking a full understanding of this moment, specifically what motivated the local people’s responses to his forceful entry onto their land.

Responding to the crew’s presence

What does it mean to accuse Cook of failing to say hello? Why was this such a blunder and what were the implications of this impolite behaviour?

Curious about the implications of what Danaiyarri said, Bird Rose asked Yarralin people what would have happened if Cook had asked properly to enter the local people’s land. She explained,

I was told that either he would have been denied permission and therefore would have gone way, or he would have been allowed to stay but only on terms decided by the owners of the country.

Cook was in Botany Bay for eight days, and throughout that time, the local people sought to impose the terms on which the crew stayed.

They kept their distance from the strangers and never opened up direct communication with them. But they also did not abandon the country to Cook’s crew. Rather, they orchestrated as best they could the crew’s presence – keeping them contained within a limited space.

They behaved, as Danaiyarri would put it, as bosses should.

Understanding why the ‘beach’ is so important

One of the marketing slogans for this year’s (now suspended) 250th anniversary of Cook’s voyage along the east coast was

the view from the ship and the view from the shore.

While it implies equal weighting would be given to understanding both sides of the story of Cook’s landing, it’s a wrong-headed idea. It suggests each party remained – and can remain still - suspended in their own separate worlds: on the ship or on the shore.

Missing from the tagline is the “beach” - the literal and metaphorical space where cross-cultural encounters, misunderstandings and, too often, violence has taken place.

As Danaiyarri reminds us, Cook did come ashore and the way he did set some of the terms for future colonial-Indigenous relations.

These encounters are challenging and complex to understand. Aboriginal stories, like those told by Danaiyarri, tell us what ought to have happened on the beach. And they ensure none of us forget where, how and why the troubles between Indigenous and other Australians began.

This year’s 250th commemoration provides yet another occasion to grapple with this difficult history – but the opportunity will be lost if we remain blinkered in seeing things only from one, or other, vantage point.

Captain Cook’s Landing Place Park.

Wikipedia, CC BY-NC-SA

Captain Cook’s Landing Place Park.

Wikipedia, CC BY-NC-SA

Authors: Maria Nugent, Co-Director, Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Australian National University